Filling the gapEstablishment of Palmer Station 50 years ago proved essential to Antarctic researchPosted June 22, 2015

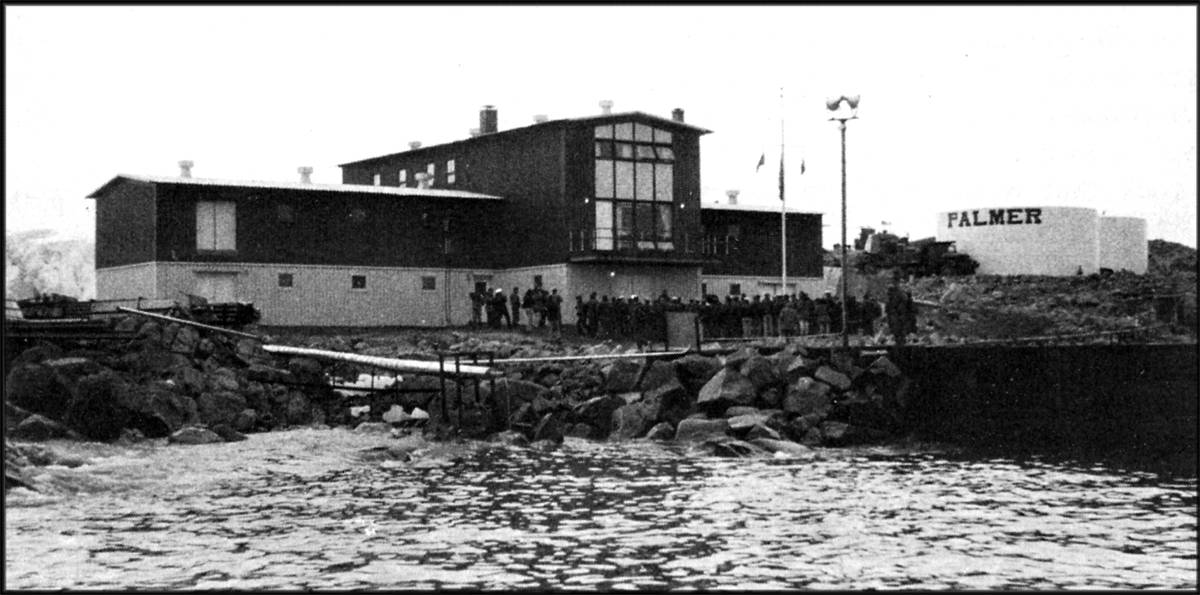

“There is no power on Earth so valuable and influential as knowledge, and full knowledge and understanding of the planet on which we live, is what mankind should seek. Antarctica is relatively unknown and forms a potential gap in our knowledge of the Earth. It is at stations like Palmer Station, that these gaps are being filled.” So said Arthur Rundle on Feb. 25, 1965, the day when Palmer Station officially opened for business. He later recorded his remarks in his final report as the station’s first scientific leader, a position he held through Jan. 8, 1967. “Biologically speaking, the peninsula is a very vibrant area. If we did not have a presence there, speaking as an Antarctic biologist, it would be a huge gap in our ability to adequately study the communities of Antarctic as a whole.” Photo Credit: Jack Cummings/Antarctic Photo Library

U.S. Navy Seabee Chuck Alletto stands in front of a newly constructed building at Palmer Station in 1965. The facility has since been removed after the new station was established in 1968.

Fifty years later, those comments come from Chuck Amsler, a professor at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, who has also served as the scientific leader at Palmer Station and currently sits as the program director of the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Organisms and Ecosystems program in the Division of Polar Programs. The smallest of three U.S. scientific outposts in Antarctica, Palmer Station is the only one of the trio found north of the Antarctic Circle, in a region with the densest concentration of international research facilities. It is located on Anvers Island, hugging Arthur Harbor, just off the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. The summertime population usually maxes out at about 44 people at any one time. The National Science Foundation (NSF), which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP), is pondering major renovations to Palmer Station on its 50th birthday. The Antarctic Infrastructure Modernization for Science (AIMS) project is a multi-year program, still very much in the early stages of development, to reconfigure both Palmer and McMurdo stations to meet the needs of future science missions. In the 1960s, when plans were first being developed to build a research station off the peninsula, the scientific goals revolved around discovery and descriptions of the natural world. It wasn’t easy work, as Rundle the glaciologist quickly discovered: “Working conditions on the ice cap are abominable for most of the year … In early September 1965, Mr. Plummer and Mr. Rundle spent 17 days camped at the northern end of Anvers Island trying to do work which really needed only two days. … The conclusion to be drawn from these experiences [is] that Palmer Station is, from the point of view of glaciological research, the most difficult United States Antarctic station to work at.” The United States had conducted a series of expeditions to the Antarctic following World War II, including the First Antarctic Developments Project (Operation Highjump) of 1946-1947, the Second Antarctic Developments Project (Operation Windmill) of 1947-1948, and the Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition of 1947-1948. Photo Credit: Jack Cummings/Antarctic Photo Library

U.S. Navy men and scientists sit down for the midwinter meal at Palmer Station in 1965.

A decade later, during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-58, the modern-day U.S. Antarctic Program would begin to take shape, with construction of seven research stations. Two of those facilities – McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station – are still active today. In addition, Byrd Station in West Antarctica is still the location of a semi-permanent field camp. The IGY had focused on glaciology, meteorology and related sciences. The decision to build a research station off the Antarctic Peninsula stemmed, in part, from the need to embrace biology and other sciences largely absent from the IGY era. A team comprised of polar scientific and logistic experts conducted an extensive survey of the peninsula region in January-February 1963. From an examination of about 30 potential station sites, Arthur Harbor on the southwestern coast of Anvers Island emerged as the one best suited to support future research, according to a May-June 1968 article in the Antarctic Journal. “The team considered the mountainous and ice-capped 24- by 37-mile island an admirable location because it is centrally located for operations over the length of the Peninsula and is about as far south as one could expect to find favorable sea-ice conditions during the austral summer,” the article reported. Early in 1964, a second survey team visited Anvers Island to determine exactly where to build the station. The site chosen, called Norsel Point, was also the one on which the British Antarctic Survey’s Base N was located, an eight-man hut erected in 1955 to facilitate geological and biological studies, according to the Antarctic Journal. The British allowed the United States to use the base, which had been deactivated in 1958, to shelter its personnel while construction was underway. The new buildings were temporary, prefabricated structures intended for only a few years of service until permanent facilities could be built. This was the station that was dedicated in February 1965. It would serve as the primary facility for about three years until the new research station at Gamage Point, about 1½ miles away, was dedicated on March 20, 1968. The station was named after Nathaniel B. Palmer, an American seal hunter believed to be one of the first to spot the Antarctic Peninsula in 1820. Old Palmer, as it would become to be known, turned into a back-up station and emergency shelter. Later, due to tightening of environmental protocols by the Antarctic Treaty System, the whole facility was eventually removed. In hindsight, the location turned out to be ideal not just logistically. Scientists have identified the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula as one of the fastest warming regions on the planet, where the average temperature has increased three degrees Celsius over the last half-century. “I thought it was an exceptional location for science. It was right on the frontier of the western Antarctic Peninsula in many respects,” noted Bill Fraser, who today is one of the principal investigators on the Palmer Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) program, which is tracking the changes to the climate from global warming. Fraser started his career in the Antarctic Peninsula in the mid-1970s, only a decade after Old Palmer was built, mainly studying seabirds, particularly penguins. Photo Credit: Kerry Kells/Antarctic Photo Library

Scientist Bill Fraser measures the length of a brown skua chick's beak. Fraser has been working from Palmer Station since the 1970s on seabird research.

“There was nothing or very little know about any of that area,” he said. “I could see nothing but possibilities there, even as a young grad student. The possibilities just seemed endless. … You had this sense that you were in the right place at the right time, if you were interested in ecology.” The living and working conditions that challenged Rundle at Old Palmer were certainly improved at the more spacious station on Gamage Point. Still, in those early days, communication was limited to ham radio. Tourists were rare. Support ships didn’t visit during the winter. “We were really isolated,” Fraser recalled. “We wouldn’t see anybody.” That’s hardly the case today. At least a dozen tourist ships visit Palmer Station each year, as well as small, private yachts. The research vessel Laurence M. Gould makes frequent port calls, even during the middle of winter. The feeling of isolation is gone, Fraser said. Recalling his first visit to Palmer Station in the mid-1980s, Amsler conceded that life at the U.S. Antarctic Program’s smallest station has evolved over the years. Still, his fondness for the place is still strong. “It still has the same feel it had my very first season,” he said. “As much as things have changed, they’ve stayed the same, too.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |