Photo Credit: James King

|

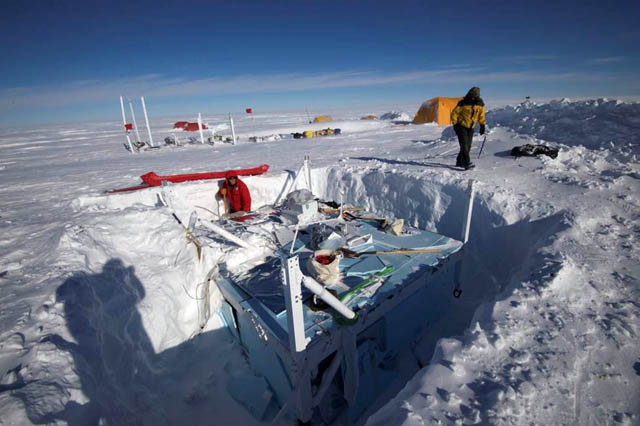

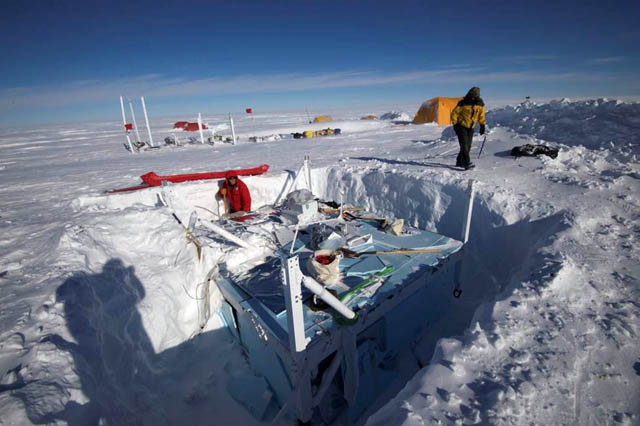

The SuperTIGER recovery team loads a section of the instrument onto an airplane. The balloon-borne instrument

landed in a remote part of Antarctica after a record-setting trip high above the continent.

|

Remote recovery

Team ventures to hinterland of Antarctica to retrieve SuperTIGER instrument

By Lyra Pierroti, Special to the Sun

Posted May 4, 2015

After more than two years since launching the SuperTIGER Long Duration Balloon, a joint team of scientists, mountaineers and support personnel finally recovered the buried instrument from a remote spot in the middle of Antarctica earlier this year.

SuperTIGER, for Super Trans-Iron Galactic Element Recorder, had flown over Antarctica from December 2012 to January 2013 to collect data for a study on the origin of cosmic rays, which are actually particles that constantly bombard the Earth’s atmosphere. Researchers can use cosmic rays to understand galactic processes and structures.

The previous recovery effort was thwarted by the partial U.S. government shutdown in late 2013. This recovery, however, would be no ordinary instrument retrieval.

“The preference is to have the payload land close to McMurdo [Station] so the recovery can be conducted in the form of day trips, and doesn’t require a deep field camp,” said scientist Thomas Hams of NASA.

But this one landed at a remote spot somewhere roughly between Union Glacier and South Pole in West Antarctica, requiring a deep-field, expedition-style recovery.

Photo Credit: Lyra Pierotti

Uncovering the SuperTIGER payload.

Armed with a GPS coordinate and a few photos from a reconnaissance fly-over mission in January 2014, the recovery team had mapped out a plan for retrieving the instrument during the 2014-15 summer.

Some members of the team – referred to as the groom team, for smoothing out a runway for a plane to land – would get dropped off as close as possible to the balloon’s payload, since landing at the site looked impossible due to the deeply cleft sastrugi snow. The groom team would then travel on snowmobiles, navigating heavily crevassed terrain, find the payload, and then set up camp, prepare a skiway, and bring in the rest of the recovery team.

All of these plans changed, however, when an early season fly-by revealed a much more friendly landing surface, and the flight operators decided they would be able to land a ski-equipped Twin Otter right next to the buried payload.

This came as a relief logistically, since the payload had somehow crash landed upside-down, and was now nearly completely drifted over with wind-hardened snow.

The payload was about six feet tall; now, it was resting six feet under.

That would mean a lot of digging.

Had SuperTIGER landed upright, the latticed landing gear would have kept the instrument elevated above the snow surface, reducing the amount of snow accumulation around, under, and over the payload.

Counting on cosmic rays

At the time it landed, the SuperTIGER flight broke the record for longest flight time of a heavy-lift scientific balloon, logging 55 days aloft.

The balloon cruised at an average altitude of 124,500 feet, but diurnal thermal changes could shift that up to 5,000 feet in either direction. That’s more than four times the altitude of most commercial airliners, and far enough from Earth to be considered “near-space.”

“At that altitude,” Hams said, “you have only 0.5 percent of atmosphere above you.”

Photo Credit: SuperTIGER

The payload launches from near McMurdo Station in December 2012.

The Long Duration Balloon, or LDB, facility launches balloon-borne instruments like SuperTIGER from a site near McMurdo Station in Antarctica.

The SuperTIGER program is a collaboration among Washington University in St. Louis, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the California Institute of Technology, and the University of Minnesota.

High-flying Long Duration Balloons allow you to do a lot of science you cannot do from the ground, Hams said, “because the Earth’s atmosphere shields us from the effects of radiation from outer space.”

Hams, 43, speaks with a gruff German accent, wields a chainsaw (and a beard) with the confidence of a lumberjack, and refers to “n” quantities of things and statistical errors even in casual conversation.

NASA had already collected the data from the instrument, but the science team hoped they could fly some of those highly valuable cosmic ray detectors again.

Among the stacked detectors is one particularly pricey component: the Cherenkov counters, which include highly specialized photomultiplier tubes and rare (and expensive) insulating aerogel.

Good thing Antarctica is a desert, because if the aerogel were to get wet, it would turn into a useless white powder.

“The point with the aerogel besides the replacement cost is that there is no vendor that could presently provide the same size and optical quality (clarity) aerogel blocks,” said Hams, who estimated it would cost half-a-million dollars to replace.

Needle in a haystack

One day, early in the 2014-15 season, pilot Troy McKerral, who was working out of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) Divide field camp, happened to be flying his Twin Otter in the area of the last known SuperTIGER payload position.

He found it, but only after flying directly over it.

The white paint job certainly didn’t make it stand out – but now it was almost completely buried in the snow.

McKerral took a picture of the site and e-mailed it to officials in McMurdo.

Photo Credit: Lyra Pierotti

A Twin Otter is used to support remote fieldwork for the SuperTIGER recovery effort.

“I had talked to him on the [satellite] phone shortly after and asked if it was landable,” said fellow Kenn Borek Air (KBA) pilot Stephen Kaizer, the one tasked with shuttling the team out to the payload.

“He informed me that it was possible but I might have to take some time to find a suitable spot – but it was ‘'better than last year.’”

Now, it was just a matter of logistics to get people and gear and planes to the site.

WAIS Divide was the obvious choice, Kaizer said, but after doing the flight planning, they realized that the amount of fuel that would have to be cached along the route to support the mission would likely leave little time for the recovery to happen before the end of the season.

Poring over a map of West Antarctica, Kaizer noticed the proximity of SuperTIGER to a place called Thomas Hills.

“We were also tasked to do some flying for a few days out of Thomas Hills for a geology group,” Kaizer said.

Using Thomas Hills as a stopover would save more than 65 hours of flying and could get the recovery team to the site in just one day. The team could then easily return with a stopover at South Pole.

“I bounced the idea off our fixed-wing coordinator, Jen Rhemann, and the Air National Guard, and they took care of all the logistics and hard work to make the plan a reality.”

After a festive Christmas holiday with the geology group at Thomas Hills, the SuperTIGER recovery team finally arrived at the buried payload on Dec. 27.

Previous

1

2

Next