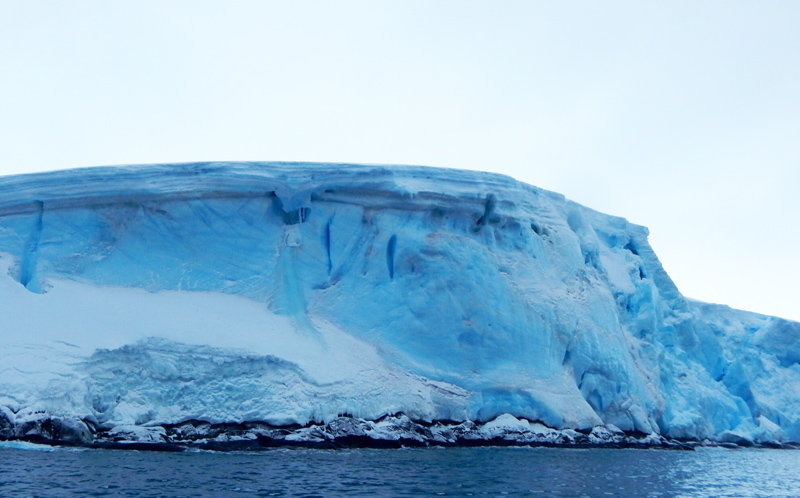

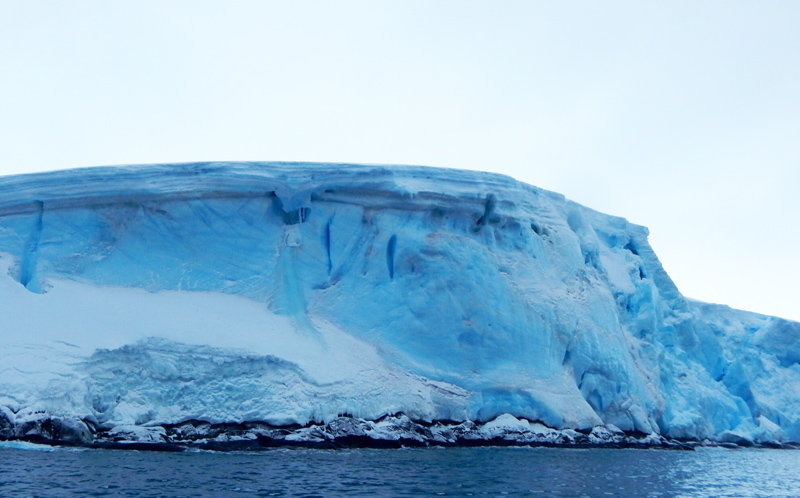

Photo Credit:Amanda Biederman

|

Glaciated mountains along the Antarctic Peninsula. The climate in this region is warming faster than

almost any other place in the world.

|

Firsthand account

Scientist experiences climate change at Palmer Station

By Amanda Biederman, Special to the Sun

Posted June 8, 2015

As a scientist in Antarctica, I find myself in a somewhat ironic situation. In some ways, I’m very removed from the real word and, subsequently, the ongoing climate change debate. There are no televisions here at Palmer Station. Our only daily newspaper is a printout of the New York Times Digest. And although we do have wireless internet, access and connectivity are limited. News such as that about the Shell scandal involving the company's lack of CO2 emission transparency, or the recent conjectures regarding the Pope's upcoming pro-climate encyclical, seems remote and slow to reach us here.

Photo Credit: Amanda Biederman

The glacier near Palmer Station is receding rapidly, with calving events happening on a daily basis.

Photo Credit: Amanda Biederman

Land is being exposed as ice melts.

But occasionally, the news hits dangerously close to home -- or, in this case, my home away from home. In May, NASA announced that the Larsen B Ice Shelf, which collapsed partially in 2002, will disintegrate completely within the next five years due to water runoff from two of the shelf's three tributary glaciers.

An ice shelf is a flat extension of ice that protrudes from the edges of the coast. They are free-floating, permanent structures that function as a barrier between the ice sheets, which are land-based, and the surrounding ocean. The Larsen, which is split into three segments and is located on the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, comprises one of the continent's 10 major ice shelves. Another team of researchers recently predicted that the larger Larsen C will disappear within the next 100 years. The Larsen A, the northernmost of the three, disintegrated in 1995.

In a study published in Science in April, researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that Antarctic ice shelves have declined significantly over the past two decades. West Antarctica -- the side of the continent where I am stationed -- is one of the most rapidly warming regions on Earth. This area has undergone constant, increasing, ice shelf loss. Average annual loss rates increased by 70 percent between 1994 and 2012 (144 versus 242 cubic kilometers per year).

East Antarctica, on the other hand, actually experienced increases in ice shelf volume between 1994 and 2003 (148 cubic kilometers per year). It was previously believed that these increases would compensate for the Western Antarctic losses. However, the researchers found that East Antarctica is now also experiencing ice shelf loss -- currently, 56 cubic kilometers per year.

Researchers believe ice shelf collapses arise from a variety of factors, including meltwater from nearby glaciers as well as surface melt due to warmer temperatures. Collapsed ice shelves, which accumulate in the form of icebergs, do not directly lead to increases in sea level because they are technically already part of the ocean. However, ice shelves separate the ocean from glacial runoff.

The melting of these exposed glaciers could produce massive changes in global sea levels. In a study published in Nature Geoscience last March, researchers found that glacial retreat in West Antarctica has contributed to melting on the east side of the continent, resulting in glacial destabilization. The current thinning of the East Antarctic Totten Glacier, for example, could eventually result in a sea level rise of at least 3.5 meters.

If the entire Antarctic ice sheet melted, global sea levels would rise by 60 meters. Much of the U.S. East Coast -- including about one-third of Maryland and the entire state of Delaware -- would be underwater. Denmark and the Netherlands would disappear. Large portions of other countries, including the U.K., China and Brazil, would be destroyed as well.

A change that large won't happen overnight, or even within our lifetimes. But the point is that we are seeing changes right now within this continent. The 2002 collapse of the Larsen B was a complete surprise; scientists literally saw a structure crumble that they had believed to be secure.

We should not take the stability of Antarctic ice for granted. Many of these changes are no longer gradual.

Christopher Neill, who conducts research in Antarctica at Palmer Station (the location where I’m currently working) a “sort of ground zero for climate change on Earth.”

“You can see these changes, and they’ve taken place in a time scale that’s really within the research career of some of the scientists that are working here,” Neill said in 2010.

This is my first trip to Antarctica, so I cannot personally confirm changes to the region (although perhaps I will when I return in 2017). However, many other scientists and staff members at Palmer have been coming to Antarctica for a long enough time that they actually have seen these changes occur.

My Ph.D. advisor, for instance, who has worked in Antarctica since 1980, has pointed out many of the changes that have occurred here over the past 35 years. A large glacier sits behind the station. In the 80s, this glacier was situated almost directly behind the buildings. Now, it's a five to 10 minute walk away. This melting has also resulted in the formation of new islands throughout the region as the ice disappears.

There are increased grasses and mosses on the rocks that were previously quite scarce. My advisor told me that after several years’ absence, she returned to Palmer and learned that an ice cave she remembered no longer existed. Another scientist from our team said that glacial calving (the process in which chunks of the glacier fall into the water, forming icebergs) was an extremely rare occurrence only 15 years ago. Now, we hear the calving (which sounds like thunder) on an almost daily basis.

When people think of Antarctica, they imagine a place that is inconceivably cold. Temperatures here average 30 degrees Fahrenheit during the summer and 14 degrees Fahrenheit in the winter. Today, in mid-May (winter in the Southern Hemisphere) the temperature was 22 degrees, including wind chill.

Palmer has been described as the “banana belt” of Antarctica, so these temperatures do not represent the temperature of the entire continent. The fact that it is (relatively) warm here is not alarming on its own. However, the average winter temperatures at Palmer have risen by 10 degrees in the past 50 years. In geological terms, that's a dangerously large change in a very short period of time.

The changes here will affect the wildlife, which may or may not be able to adapt to a warmer climate. The fish that I study, icefishes that lack hemoglobin, are extremely sensitive to even slight changes in temperature. Warmer water temperatures have already allowed for species invasions -- namely, the king crabs.

Climate change threatens the scientists here. Expanding sea ice coverage is limiting access to the continent, and the ice sheet melting could cause damage to station infrastructure.

But the reality is that the loss of ice coverage in Antarctica isn't just about the penguins, the seals and the fish. And it isn’t just about the science stations. It isn't just that we are could be destroying the last untouched region on Earth. By altering sea levels in both the northern and southern hemispheres, these changes will directly impact all of us.

And these rapid changes demonstrate how quickly even moderate increases in temperature can affect the Earth. This is not an issue that will be resolved on its own, and the time for making the environmental protection a priority is long past due.