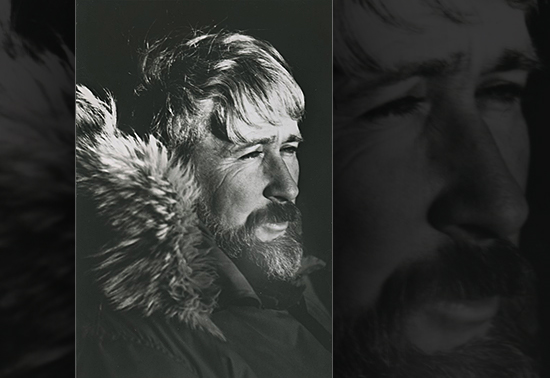

Photo Credit: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library

|

Stewart poses for a portrait in McMurdo Station while wearing his Antarctic parka. He traveled to Antarctica numerous times over

the years to set up and oversee the scientific diving on the continent.

|

James Stewart

He Set the Diving Standards For 50 Years

By Michael Lucibella, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted July 12, 2017

James "Jim" Stewart-- the chief diving officer emeritus at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the so-called "father" of the U.S. Antarctic Program's diving program—died in Irvine, California on June 7 at the age of 89.

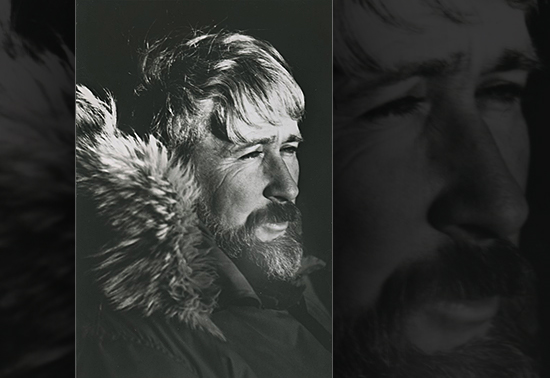

Photo Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego

Stewart, wearing his scuba equipment, emerges from the ocean. His career as Dive Officer for Scripps took him to dive sites around the world.

In 1967, the National Science Foundation wanted to formalize its scientific-diving procedures and brought in Stewart to help set up policies and best practices for researchers diving underneath the Antarctic ice. Up to that point, scientists had largely been left to their own devices to conduct their own diving with little oversight.

“He immediately set up a first-rate dive locker for us to use and he did a terrific job overseeing the diver safety,” said Paul Dayton an oceanographer who had spent decades diving in Antarctica, often with Stewart.

Jim Mastro, who was the scientific diving coordinator for McMurdo Station from 1990 to 1996, added that “it’s safe to say that James Stewart was the father of the USAP diving program. His influence is still felt today and will be for as long as the program is in existence.”

Stewart had been freediving—diving without breathing equipment--since he was 14 years old. After a stint in the U.S. Army Air Corps, he joined the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, in the early 1950s to develop the first guidelines for scientific diving practices. He became Scripps’ diving officer in 1960, a position he held until his retirement in 1991, overseeing the country’s largest and oldest nongovernmental research diving program. Even after retiring, he remained active at the institute, and continued to return to Antarctica.

Stewart adapted the scientific-diving best practices that he helped develop for the American Academy of Underwater Sciences to produce the polar-specific “Guidelines for the Conduct of Scientific Diving” for the U.S. Arctic and Antarctic programs, procedures still used to this day.

Over the years, Stewart returned to McMurdo and Palmer stations numerous times as the program’s dive-safety officer to review diving practices and safety. His philosophy was to make good scientists into safe divers so they could do their own research the way they needed to.

“This attitude of supporting science is Jim’s greatest legacy, not only in the Antarctic, but worldwide,” Dayton said.

“When I became the Dive Services supervisor, Jimmy took me under his wing to help me navigate the vast differences between science and commercial diving,” said Rob Robbins, the program’s current dive supervisor. “Without his tutelage, I certainly would have floundered.”

Those who knew him remember him also as a warm and gregarious person.

“I had the pleasure of hosting visits by Jimmy to both McMurdo and Palmer in his role as USAP Dive Safety Officer. During these visits was always helpful and entertaining,” Robbins said.

“He always had a story to tell,” Mastro added. “His diving career was a legend even then, and he had plenty of tales to tell of diving all over the world.”