Photo Credit: Rob Jones |

At McMurdo Station, the flags of the original 12 signatory nations to the Antarctic Treaty flap in the breeze around a bust of Admiral Richard Byrd. |

The Antarctic Treaty's Diamond Anniversary

After Sixty Years, the Antarctic Treaty Remains a Landmark of Diplomacy

By Michael Lucibella, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted December 2, 2019

Sixty years ago, on December 1, 12 nations signed an unprecedented international agreement that set aside their often-contentious territorial claims on the frozen continent and established Antarctica as a place for peaceful coexistence to facilitate scientific research by all nations.

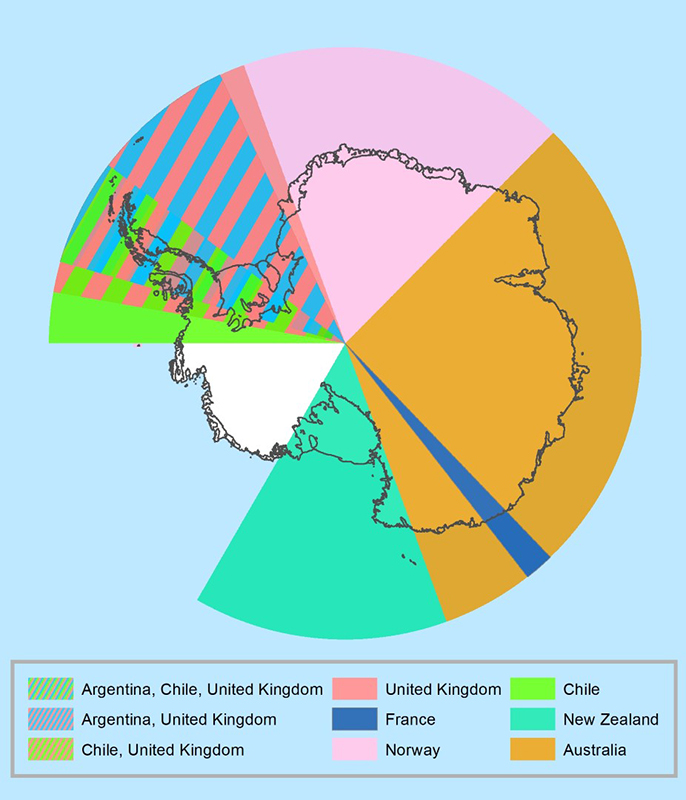

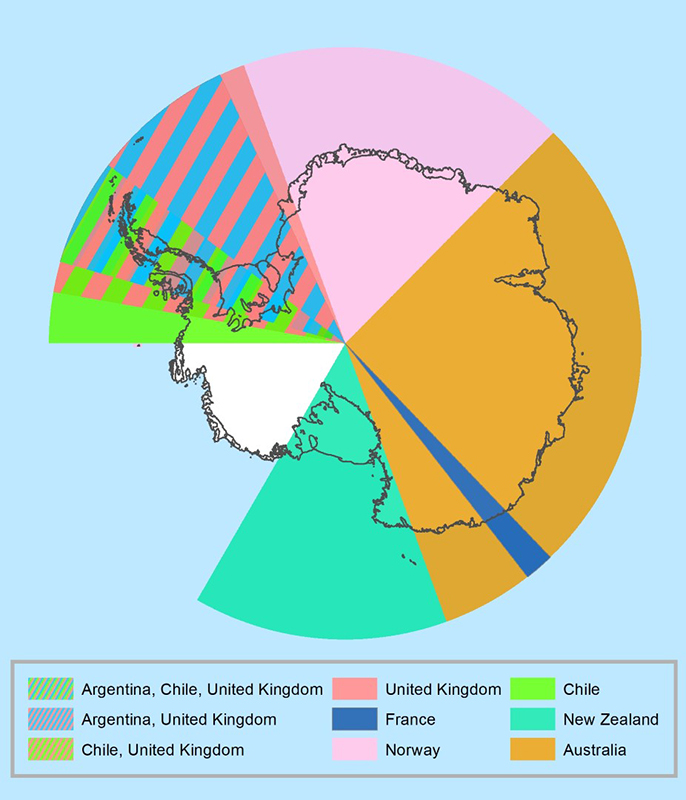

Photo Credit: Geospatial Center

Before the Antarctic Treaty, seven nations made sometimes-overlapping territorial claims around the Antarctic continent. One of the key provisions of the treaty is these claims are set aside for the free exercise of science.

The treaty is a remarkable document, in part for its expansive scope but also for its brevity. Contained in a mere 12 pages is the governance of a continent larger than Europe, covering nearly nine percent of Earth's landmass. Its four main points froze territorial claims to the continent, outlawed nuclear weapons and waste on the continent, preserved the entire region south of 60 degrees south latitude for peaceful science, and outlawed military actions, making it effectively the first nuclear-arms control agreement in history.

The original 12 signatories were Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Now, more than half a century later, 54 nations have signed onto the treaty, which has expanded to include some of the most rigorous environmental protections on the planet.

The National Science Foundation manages the United States Antarctic Program, through which the nation meets its treaty obligations to maintain an active scientific presence on the continent. But other federal agencies, most notably the U.S. Department of State, play a major role in meeting the nation's overall Treaty requirements.

Though the treaty is today firmly established and respected around the world, when it was first signed in 1959, at the time, no equally ambitious international agreement had ever been attempted.

The document's preamble lays out its goals: "It is in the interest of all mankind that Antarctica shall continue forever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes and shall not become the scene or object of international discord [and] acknowledging the substantial contributions to scientific knowledge resulting from international cooperation in scientific investigation in Antarctica."

Photo Credit: Cliff Dickey

The numerous nations participating in the International Geophysical Year in Antarctica showed that peaceful coexistence for science was possible and emphasized the need for a more permanent solution to the administration of the continent.

Countries and historians still debate who first saw the continent around 1820. In the 20th Century, seven nations publicized specific territorial claims. Some of these territorial claims overlapped with others. The United States and the then Soviet Union hadn't laid out formal claims over any territory but were known to object to the seven territorial claims and were expected to make their own claim at some point. The issue of territorial claims led to international tensions.

Between July 1957 and December of 1958, 67 nations around the world put aside their differences to participate in the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a global, 18-month international effort to study Earth science. It led to the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, the mapping of ocean ridges which contributed to the discovery of plate tectonics, and a global effort by a dozen nations to explore Antarctica, a vast swath of the planet that was still terra incognita. A core tenet of the IGY was setting aside international politics and disputes for the sake of science.

But this situation highlighted a dilemma for the world because virtually all the IGY nations indicated an interest in continuing their research in Antarctica after its conclusion in 1958, a potentially untenable situation if nations decided to assert their authority over their claimed territories. The Cold War's tensions were also in play with regard to Antarctica, particularly with the potential nuclear weapons to be tested or its waste to be deposited there. However, the success of the IGY showed that peaceful scientific cooperation was possible even as tensions flared between east and west.

As the IGY drew to a close, diplomats mulled how to administer Antarctica now that there were dozens of stations from numerous nations scattered across the continent: reverting to a collection of overlapping international claims seemed untenable.

But the idea of setting aside territorial claims and bringing the whole continent under an international agreement had been contemplated in various forms, and for the first time it started to seem like a realistic option.

Working behind the scenes, U.S. diplomats started to lay the groundwork among nations that participated in the IGY to accept the idea of an international treaty for administering the continent. On May 3, 1958 President Eisenhower publicly invited the twelve nations that participated in the Antarctic IGY to travel to Washington DC to forge such a treaty. In his announcement, Eisenhower echoed the call to set aside the continent for peaceful scientific purposes.

After nearly 18 months of preliminary negotiations, which included the United Kingdom urging the members of the Commonwealth to support a treaty, diplomats from the 12 participating Antarctic IGY nations arrived in the nation's capital in October 1959 to negotiate the Antarctic Treaty.

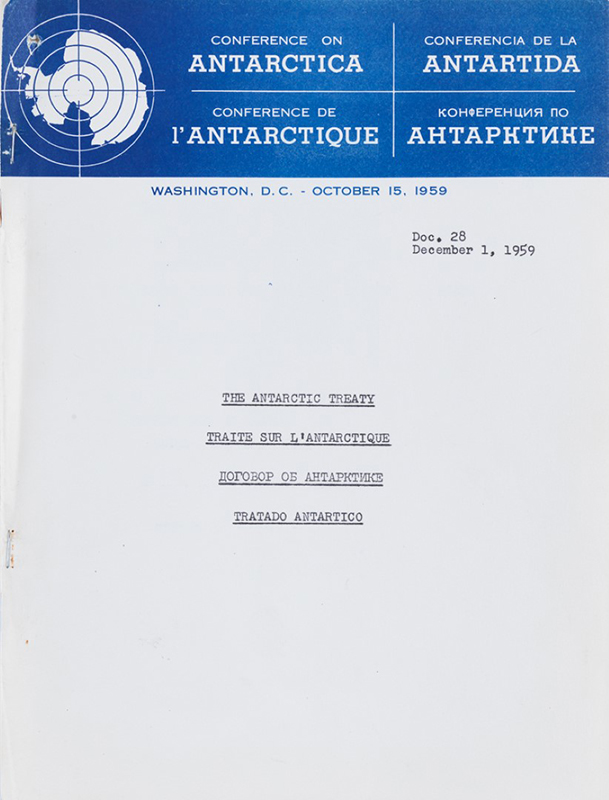

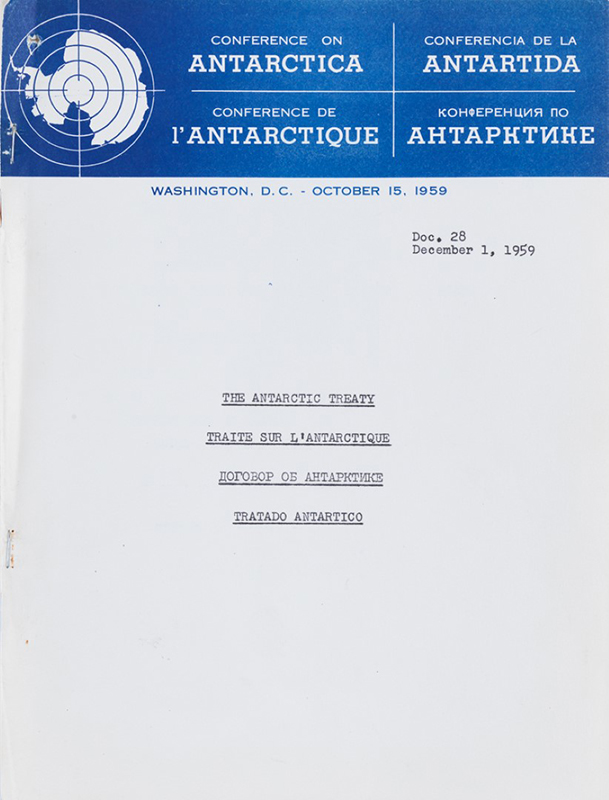

A month-and-a-half later, on December 1, 1959, the 12 nations signed the Antarctic Treaty at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C.

Its influence expanded well beyond Antarctica, laying out the groundwork for the future Outer Space Treaty signed eight years later which similarly set aside space as a place for the human race's peaceful pursuit of science, free travel without national claims, nuclear weapons or nuclear waste.

Photo Credit: The National Archives of Australia

After years of uncertainty and months of intense negotiations, the Antarctic Treaty was signed on December 1, 1959, establishing the continent as a region devoted to free and peaceful science.

Since the signing of the treaty, additional environmental protocols have been added to the core document, strengthening the ecological protections of the continent. The first was the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, ratified in 1972 to regulate an expected, but never realized, return to commercial sealing. In response to overfishing that had depleted many stocks throughout the Southern Ocean, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, the world's first ecosystem-based fisheries management treaty, was signed in 1980. Then in 1991, signatories to the treaty agreed on the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which detail the extensive environmental protections for the continent. It expressly forbids any kind of efforts to exploit Antarctica's mineral reserve, a provision that has no expiration date.

The treaty continues to govern every activity on Antarctica. All scientists, support staff, and tourists must abide by the environmental protections.

Each year representatives from the treaty nations continue to meet and discuss the management of the Antarctica and the surrounding ocean. Over the decades, the big issues facing the continent have evolved. Concerns about nuclear weapons testing and international power struggles that were so pressing in the 1950s have given way to concerns about understanding the effects of climate change and managing a booming tourism industry.

At the 2019 meeting of the Antarctic Treaty in the Czech Republic, nations reaffirmed the strong commitment to the objectives and purposes of the Antarctic Treaty, its Protocol on Environmental Protection and other instruments of the Antarctic Treaty system, including the indefinite prohibition of any activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research. The countries also pledged to further strengthen efforts to preserve and protect the Antarctic terrestrial and marine environments and to promote co-operative scientific, technical and educational programs and outreach activities.

The treaty remains open for countries to join in order to ensure that Antarctica's next 60 years are reserved for peace and science.