|

Fly away AntarcticaSladen, 86, returns to continent for new film nearly 60 years after pioneering penguin researchPosted January 28, 2007

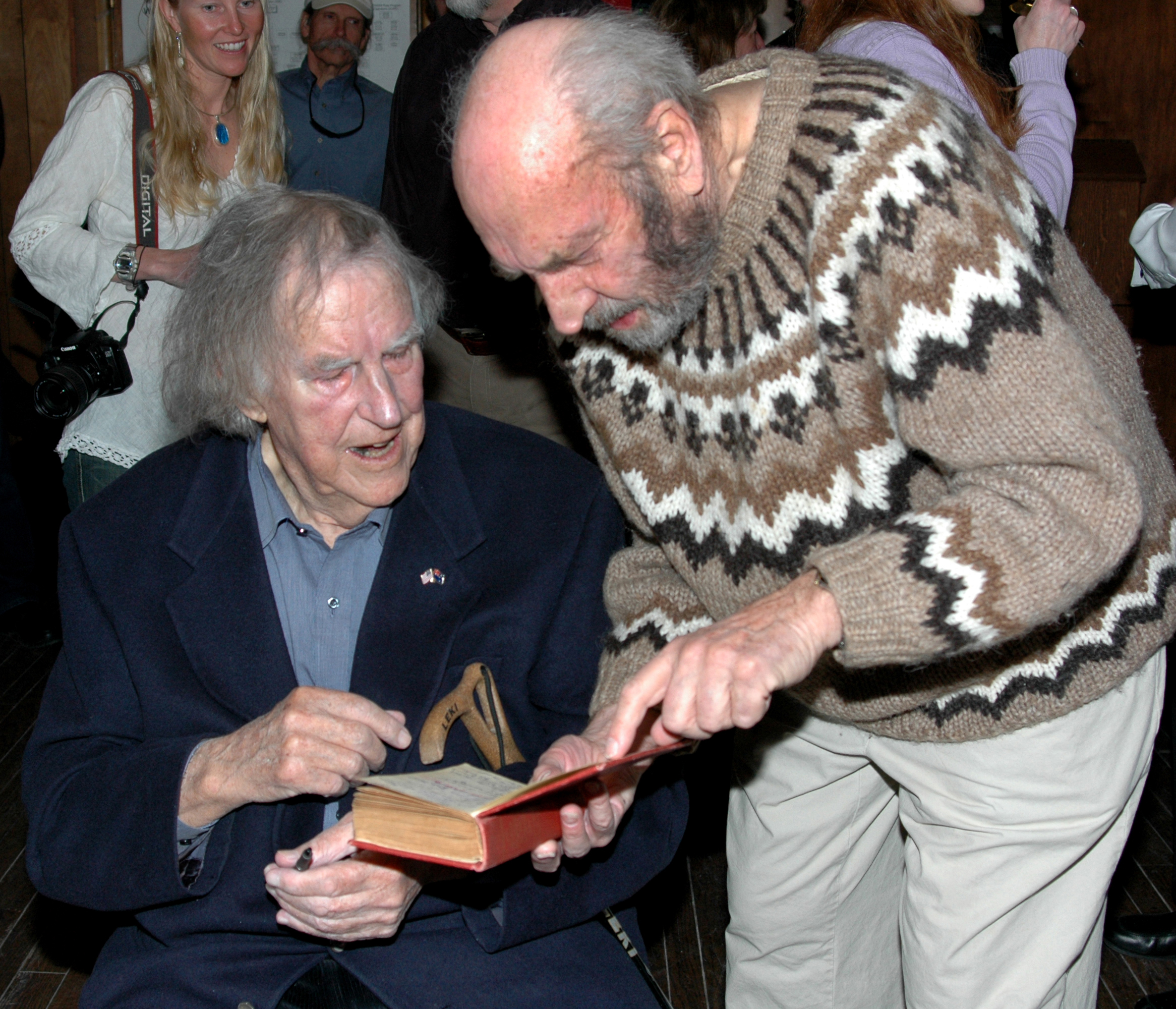

A business card can sometimes tell a lot about a person, more than just name, rank and phone number. Take the card handed out by Bill Sladen. The first thing that catches one’s eye is the artwork, a silhouetted image of a person in an ultralight aircraft, followed by seven long-necked birds in flight. It lists the Web site trumpeterswans.org. Then one notices the name: “William J.L. Sladen, M.D., D.Phil.” At the bottom of the card, it is noted that he is a professor emeritus at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. In the middle is his contact information ... to one side. On the other side is complementary information for Environmental Studies at Airlie, a division of the International Academy for Preventive Medicine. At 86 years old, Sladen would be promptly forgiven for handing out cards that say, “Retired – No Job – No Worries,” but a quick conversation gives the impression that he has no interest in slowing down, especially while visiting the continent he first saw just shy of 60 years ago. A noted ornithologist, he is at McMurdo Station for the first time since 1970 (though he sailed the Weddell Sea for his 80th birthday) to complete something of a circle in his work with Adélie penguins. From 1959-1970, Sladen conducted an ongoing study of penguins at Cape Crozier and Cape Royds. An avid photographer, he filmed “Penguin City,” which was broadcast on CBS and BBC TV. During the last two years of his study, he was assisted by graduate student David Ainley, who resumed the penguin studies a couple of years after Sladen left and has maintained them since. Sladen’s most recent trip to the Ice was to assist filmmaker Lloyd Nales with a new film, “Penguin Science,” about Ainley’s work. Sladen says they are updating his original film for the International Polar Year, which begins in March.

Early daysSladen says there were two stages to his Antarctic career. The first was set by him initially pursuing a medical degree in his native England during World War II.“Being a medical man,” he says, “I got the job [in the Antarctic] and then I was able to do the biology I most wanted.” His first year in Antarctica began in the 1948-49 summer as part of the Falkland Islands Dependency Survey, now called the British Antarctic Survey. “For the British, I was medical officer and biologist — amateur biologist, because I didn’t have a degree in biology — and photographer.” His group put in at Hope Bay on the very tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. “It ended up with a lot of tragedy,” Sladen says. “I started my penguin work, and the colony was about a mile from our hut. I lived in a Scott polar tent there. One day, I came back in a blizzard and found the whole hut blazing. Actually, it was a tragic fire. The rest of our team was out surveying by dog sledge, and we lost [scientists Oliver Burd and Michael Green] on that occasion. I was by myself in a tent for about two or three weeks.” He spent the next year at Signy Island in the South Orkneys. He did research on penguins those two years that earned his doctorate in zoology at Oxford. He also researched upper respiratory bacteria and pathogens in his teammates to finish the requirements for his second medical degree. Then came the event that set the second stage of his Antarctic experience. He received a Rockefeller Fellowship to come to the United States in 1956, and he got involved in the first stages of the U.S. Antarctic Research Program. “At that time, I helped establish the first bio-medical program of USARP and, of course, a study of the Adélie penguins at Cape Crozier,” he says. “Actually, we made the first banding in 1959 with Navy help from the icebreaker Staten Island, but started seriously in 1960. That continued until 1970, when I did my last season there.” The close monitoring that goes with the program is quite interesting, he says. “If you know these birds as individuals, it’s really fascinating, absolutely fascinating,” he says. “The older birds come back each year and tend to keep their original mates. The ‘divorce rate’ in the younger birds is about the same as in America. That is why we called it ‘Penguin City.’”

To the ArcticIn the late 1960s, Sladen also spent time in the Arctic, studying swan and goose migration, as he studied the South Polar skua in Antarctica.In 1975, he was invited to Wrangel Island in Siberia, where Russian snow geese breed. They winter in British Columbia, Washington or California. His work teaching migratory routes to young geese, cranes and swans earned him a footnote in pop culture as well when he served as wildlife consultant to the popular 1996 movie, “Fly Away Home.” As in the fictionalized movie story, his program has used ultralight aircraft, as well as ground-based methods, to teach routes to birds. Unlike many smaller birds that migrate instinctively, birds such as the trumpeter swan must be taught migration routes. Sladen says that once these orphaned birds, whose parents have died or become unable to fly, are led from their breeding grounds to winter nesting areas, they find their way back and will repeat the course the next year. Currently, he’s seeking funding to test a hypothesis that the birds can learn the routes passively. The plan involves suspending caged birds underneath a dirigible type of airship and traveling the migration route. Such a procedure would be much safer for humans and less expensive, he says. Maybe there’s room at the bottom of his business card.

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |