Page 2/4 - Posted November 13, 2009

Preparing for HistoryHowever, McWhinnie would have to wait for the Ohio State team to break the ice in 1969, though technically the first female scientist to work in the U.S. Antarctic Research Program (which would later drop “Research” from its title) would beat Jones’ team to the continent by a few weeks. Christine Muller-Schwarze, a psychologist from Utah State University, joined her scientist husband at Cape Crozier in October 1969 to study penguin behavior. Later quoted in the book “The New Explorers: Women in Antarctica” by Barbara Land, the German-born scientist said she wasn’t trying to set a record. Their reason for an early arrival was scientific. “We just wanted to be at Cape Crozier when the first penguins arrived to choose their nest sites.” Meanwhile, Jones was assembling her team at Ohio State. Eileen McSaveney was no stranger to being in the minority when it came to the sciences. At the University of Buffalo, she was the sole female undergraduate student in the Geology Department. The ratio of young female scientists went up when she arrived at Ohio State for her graduate work. She was already familiar with the Antarctic research program when Jones asked her to join the first all-woman field party in 1969.

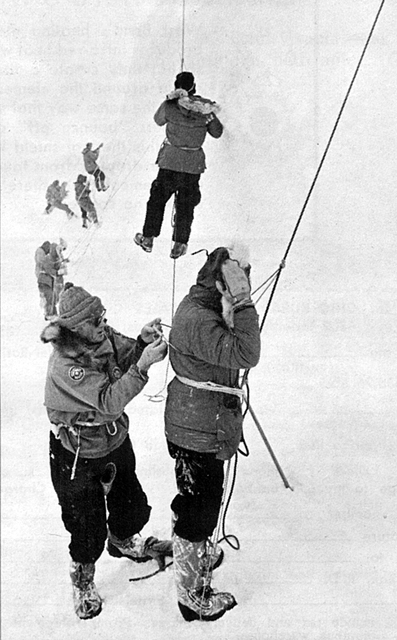

Photo Courtesy: Terry Tickhill Terrell

Terry Tickhill Terrell learns survival skills before heading to the Dry Valleys.

“I thought about it for a while — about half a second — and said yes. It didn’t seem out of the ordinary. My then-fiancé Mauri — we have now been married for 40 years — had already been to Antarctica that year, and many fellow geology grad students were involved in polar work through the Institute of Polar Studies,” she says via e-mail from New Zealand, where today she works as an editor and writer in earth sciences. Kay Lindsay was the third member of the team. Though an entomologist on a geologic expedition, Lindsay’s husband John was a geology grad student and had also been to Antarctica. Bull says the National Science Foundation (NSF) And Terrell? “I never could invent any Antarctic experience for her, but she was really good at stripping down a motorbike, or a radio, or a Primus [stove],” Bull says. “She was someone anyone would want in an [expedition] party.” Terrell confirms that her down-on-the-farm work ethic and vigor proved to be assets in the field. “I’m not a tiny person. The work was hard. [Jones] was looking for someone who could carry a 65-pound backpack and a 13-pound sledgehammer around and collect rocks.” Busting Into HistoryThe announcement of an all-woman science team headed to Antarctica drew plenty of media attention though much of it reflected the bigotry of the times, with headlines like, “Powderpuff explorers to invade South Pole.” Reporters asked hard-hitting questions like, “Will you wear lipstick while you work?”

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy

Lois Jones stakes down a tent at the team's camp near Lake Vanda in Wright Valley.

McSaveney recalls that the first journalists to show up at Ohio State were from the local Columbus newspaper. “They weren’t satisfied with boring ordinary pictures of the group, so we donned heavy parkas and trooped down to the Institute’s ice core cold rooms, where we could be photographed looking at some cores (even though Lois’s project had nothing to do with ice cores).” Predictably, the Navy, while finally relenting on the prohibition on women in Antarctica, was skeptical of the expedition. “They definitely made it very obvious that there was a concern that we wouldn’t make it,” says Terrell, which only goaded the team to work harder than the male researchers in the field. “Two thousand people a year manage to make it,” she adds. “Why wouldn’t we be able to make it? It just didn’t make sense to me that we couldn’t do it. I didn’t feel so much pressured [to succeed] as amused that they would think we were so unable to do the same sorts of things the men were.” But attitudes were already changing, and Terrell says the experience was largely positive. “There was a tremendous amount of support,” she says. “There was a large number of people who thought this was a great idea.” The four women spent most of their time working in the moonscape of Wright Valley, making only brief visits to McMurdo Station to shower or do laundry. “Our time spent in McMurdo was often amusing,” McSaveney says “The Navy officers treated us with almost elaborate courtesy, but several poor Navy enlisted guys who used bad language within earshot of us got a tongue lashing.” One time Terrell noticed a fellow following her around McMurdo. Later, she saw him sitting on a porch crying. She asked him what was wrong. He said, “I think you’re a woman.” Terrell assured him that’s what she thought as well. Apparently, the Navy hadn’t told most of the enlisted men that there were going to be women there — a particular shock to those who had been on the Ice for more than a year. “The thing that struck me was how unnatural it was. The pressure situation must have been so much worse before we arrived — not just us, but women in general,” she says. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |