Page 3/4 - Posted November 13, 2009

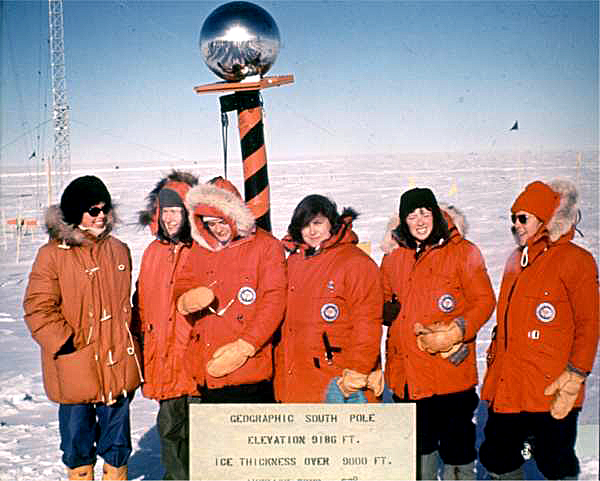

History at PoleAt first leery of the gender experiment in Antarctica, the Navy later embraced the opportunity to show off its progressive attitude with a media event at South Pole Station A ski-equipped LC-130 flown by the Navy took the women to the South Pole on Nov. 12, 1969. By that time, there were seven women in Antarctica. Jones’ team was working the Dry Valleys. Muller-Schwarze was with her husband at Cape Crozier. Pam Young was a young Kiwi biologist doing research with the New Zealand Antarctic program. And Jean Pearson, a respected science writer for the Detroit Free Press, was on the Ice filing news reports. Rear Adm. D.F. Welch, the commander of the naval forces in Antarctica, escorted the six women to the Pole. (Muller-Schwarze declined to go because she was busy with her work.) His aide, then-Lt. Jon Clarke, helped orchestrate the moment when all six women would step off the cargo ramp at the back of the plane.

Photo Courtesy: Terry Tickhill Terrell

Eileen McSaveney and Terry Tickhill Terrell drill into Lake Vanda.

Who would be the first woman to step on the Ice? “The admiral decided [King] Solomon-like that the solution to that problem was that all [six] of them could jump off the ramp at the same time and they could all claim to be the first at the Pole. I was the guy in charge of stage managing that event,” says Clarke, who left active service in 1970 to go to law school. He has a law office outside of Denver. Photographers filmed and shot every moment, from the first steps on the polar plateau to the group picture at the geographic pole that marks 90 degrees south. Terrell admits the event was overly staged, but also says the visit probably held more meaning for Jones, who was older than the rest of the team and had faced gender discrimination for years. It also served as an example that women could be more than nurses or teachers, as she’d been told in grade school. “That’s what the teachers were telling the kids: Their opportunities were extremely limited,” Terrell says. “To me, [the visit to South Pole] was in part to say, ‘The only bounds you have are the ones you put on yourself.’” In the fieldAway from the spotlight, the Ohio State team stayed busy with its fieldwork in the Dry Valleys, which involved living out of tents on the edge of Lake Vanda, melting ice for water, and hiking with rock-laden backpacks. “We didn’t disgrace ourselves by needing to be rescued, so I presume it made things easier for the next women proposing to go south,” McSaveney says. “We had some minor difficulties — we were by and large urban women rather than outdoor enthusiasts.” The women, like all scientists headed into Antarctica’s backcountry, received survival training. Though it didn’t cover everything, McSaveney recalls. “We had a very cold first few nights in Bonney Hut in Taylor Valley because no one had thought to show us how to start and run the hut’s unique oil drum heater,” she explains. “Afraid of blowing up ourselves, or the hut, we waited several days until someone could show us the procedure, which was quite simple once you knew how.” Cold temperatures and finicky heaters weren’t the only dangers. Two helicopters crashed that season. The first accident killed several people, Terrell says. The Ohio State team was involved in the second crash — a very hard landing. “On the way down, I wasn’t so sure how it was going to end,” she recalls, adding that the now-experienced field team of women ended up having to show the helicopter pilots how to set up a tent while they waited for rescue. Helo visits were generally few and far between to their camp at Lake Vanda. The women rarely called in for additional supplies — unlike the men when they ran out of libations, according to Terrell. “We were considerably less bother than the men,” she says. “That was intentional. Dr. Jones was very concerned about being less bother. She had her professional career based on this. She was very concerned about making sure this was a very successful field season.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |