|

Page 2/2 - Posted October 15, 2010

Stamp on historyToday, polar philately is a hobby — albeit a serious and expensive one for some collectors — but in the nascent scientific age of the 1950s, it also was a political tool. Related Articles

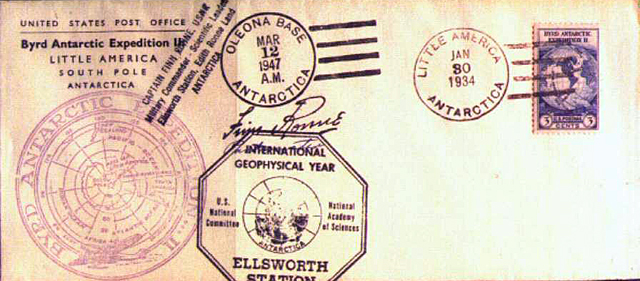

No one nation owns Antarctica. However, until the world generally agreed to suspend all property claims with the signing of the Antarctic Treaty The United States didn’t make a claim nor did it recognize any other territorial claims. But that didn’t stop some subtle — and not so subtle — attempts during the 20th century to legitimize any possible future claims. One weapon in this diplomatic war was establishment of a post office on the continent. “If it ever got around to people recognizing different claims, and if we had set up post offices and done philatelic mail over certain sites, that would help us in that process,” explained Bob Chaudoin. Chaudoin was a young Navy enlisted man in 1955 when he chose to give up an assignment in Paris for an eventual post at the South Pole during Operation Deep Freeze, the military mission during the IGY. His background working the mailroom at a Navy base in Hawaii was enough to qualify him for the job of postal clerk. In the austral summer of 1956, he joined members of the Seabee Construction Battalion to build the first research station at the geographic South Pole. He and weatherman Jerry Nolan paused for two 12-hour days to cancel some 500,000 first-day covers (the front of the envelopes), using the first hut built at the new station. The first cancel was Dec. 15, 1956. “There was no postal clerk in the Antarctic at that time handling the mail,” said Chaudoin, only recently retired at age 81 and living in Florida. “What the postal clerks were designed for was to cancel philatelic mail that was going to be handled at Little America and at the Pole.” The job of handling regular mail, as well as more bags of philatelic mail, fell to Earl Johnson, who wintered over at South Pole in 1957 with 17 other men, including Siple, the famed scientist who partly inspired Vogel to become a polar philatelist. Johnson and Chaudoin never crossed paths at South Pole, likely missing each other by just a few days. A “whole bunch” more philatelic mail awaited processing. Johnson also made souvenir covers for the 18 South Pole winter-overs, each of whom signed the machine and hand-stamped envelopes for what today is a highly valued collectible. “South Pole is the ultimate desire. Everybody knows South Pole,” Smith noted. “When you think of Antarctica, you think of the South Pole.” Beth Watson estimates the South Pole Station receives about a thousand pieces of philatelic mail a year. “You get them from everywhere,” said Watson, former South Pole Station Support supervisor for the USAP who oversaw the all-volunteer post office. Smith said he probably canceled about 10,000 pieces himself over the years. Priceless secretsThe South Pole wasn’t the first place where the United States attempted to surreptitiously gain a territorial foothold in the Antarctic through the U.S. post office. One of the more famous — but totally secret at the time — philatelic operations took place under Finn Ronne The Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (RARE), from 1947-48, was the last privately sponsored expedition from the United States and the first to include women in the winter-over party. Ronne established the Oleona Base on Stonington Island off the Antarctic Peninsula, where he canceled about 25 envelopes on the opening and closing dates of the expedition. It turns out that before he left for Antarctica, Ronne had been secretly sworn in as a 4th class U.S. postmaster. “It was a territorial claim,” Smith said. “The United States made him a postmaster down there to cancel envelopes to counteract the British claim to that part of Antarctica.” There were several different aspects that could constitute a geographic claim, Vogel explained. One is having an active, bureaucratic management, which can be represented in the form of a post office. “Having a post office and issuing stamps for an entity is considered one of the important aspects in a case for a geographic claim,” Vogel said. Needless to say, RARE covers are extremely valuable among polar philatelists. One particular cover was canceled three separate times by Ronne. Once during his tenure with Byrd during the latter’s second Antarctic expedition in 1934. A second time at Oleona Base. Finally, a third time when Ronne was the leader at Ellsworth Station during the IGY. Smith has one in his possession today, worth about $2,500. For collectors like Smith and Vogel, however, such pieces of polar history are really priceless. “There’s a lot of history. The history is a large part of my interest,” he said. “I’m a stamp collector. It’s fun for me.”Back 1 2 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |