What's in a name?No international guidelines exist for national committees on geographic featuresPosted July 18, 2014

More than 100 features in the Sentinel Range, a mountain range that comprises the northern half of the Ellsworth Mountains in West Antarctica, sport names like Ahrida Peak, Padala Glacier and Lardeya Ice Piedmont. Ahrida is the medieval name of the Eastern Rhodope Mountains in Bulgaria. Padala is a settlement in western Bulgaria. Lardeya refers to a medieval fortress in southeastern Bulgaria. The prevalence of Bulgarian names in the 115-mile-long mountain range has raised the eyebrows of at least one long-time person associated with the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) John Splettstoesser “I think this is something that should not be taken lightly,” he said. Eight of the 10 highest peaks in Antarctica are found in the Sentinel Range, including the tallest mountain, Vinson Massif. The 16,050-foot-tall mountain is named after U.S. Rep. Carl G. Vinson of Georgia whose “active interest and vision played a large part in U.S. government support of Antarctic exploration in the period 1935-61.” Lyubomir Ivanov, chair of the Antarctic Place-names Commission within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria

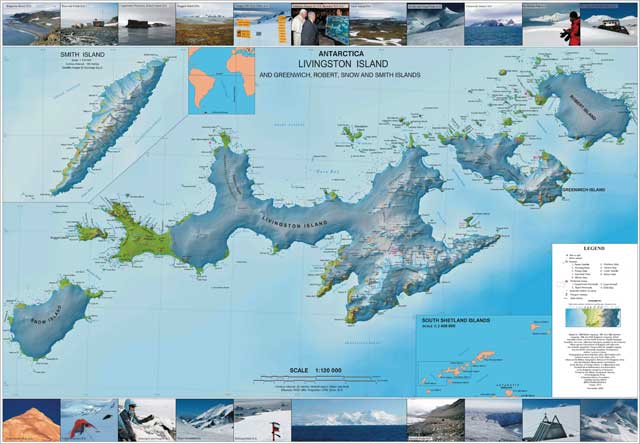

Photo Credit: Bulgarian Antarctic Place-names Commission

Map of Livingston Island and nearby islands produced by Bulgaria.

“The 1995 Toponymic Guidelines of the Antarctic Place-names Commission of Bulgaria Locations where Bulgarian scientists have worked do play an important yet partial role, according to Ivanov. For instance, the Bulgarian Antarctic Institute “We mostly give names where we believe that they would be most useful for potential users including scientists (both for fieldwork, publications or other scientific use), map makers, logisticians, navigators and tourists,” Ivanov explained. “In all cases the prospective features must be nameless, well identified and provided with detailed standard descriptions.” Photo Courtesy: Charles Bentley/Antarctic Photo Library

Charles Bentley, far left, and members of the Sentinel Mountains traverse team.

Most of the other named features in the Sentinel Range were mapped during seismologist Charles Bentley’s Mount Bentley, at 14,022 feet, bears his name in the mountain range that was discovered on Nov. 23, 1935, by Lincoln Ellsworth in the course of a trans-Antarctic flight from Dundee Island to the Ross Ice Shelf Since 1996, naming activities have been coordinated by the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR) The SCAR Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica “The composite gazetteer is simply a compilation of the place names from national gazetteers and does not in any way vet or make judgments on those names (though we have in the past provided advice on ‘best practice’),” said Mike Sparrow The southern half of the Ellsworth Mountains is referred to as the Heritage Range, a place where Splettstoesser said more accurately reflects what he considers proper naming protocols. The combination of names approved by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names “All the names we proposed were a factor of ‘boots on the ground’ and merited as a result,” Splettstoesser said. The McMurdo Dry Valleys “I have no objection to the density of names on virtually every possible feature, but the process seems to invite a ‘dumping ground’ of naming of features because the topographic mapping is thorough and precise,” he said by e-mail, “and it is also an area (with mainly bedrock exposures) that invites a search for an unending process of finding new features for new names.” Splettstoesser said “raising the bar” for naming of future geographic features, as the United States has recently done with the application of personal names, appears to me to be a step in the right direction. “A consensus of all [Antarctic] Treaty parties to adopt a sensible set of guidelines would also seem to be an insurmountable task,” he said, “whether taken by SCAR or any other Treaty body of authority.” Return to main story — A new standard: U.S. 'raises the bar' on using personal names for geographic features in Antarctica. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |