Past connectionsYoung ham radio operators kept IGY crew in touch with friends, familyPosted January 30, 2009

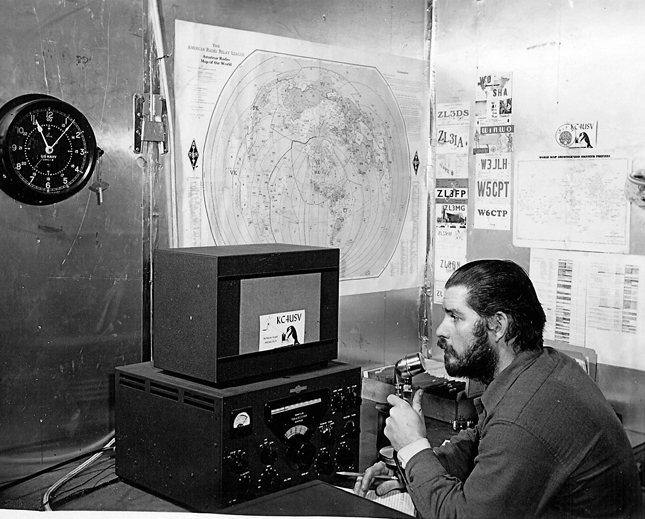

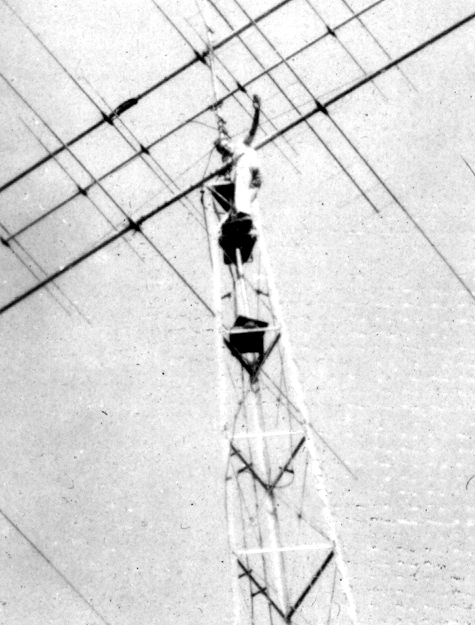

Madey Ridge, located in Antarctica’s Pensacola Mountains near the Ronne Ice Shelf, is named for a teenager who played a critical role in the lives of hundreds of Antarctic pioneers. Today, ask any number of retired Navy Seabees if they remember a Jules Madey and every one of them will happily tell you that Jules was one remarkable young man. In 1955, the U.S. Navy sent hundreds of Seabees, the Navy’s construction battalion, to Antarctica to build seven research stations for the impending International Geophysical Year (IGY) Ham radio was the only means of talking to loved ones back home in the era preceding satellite-enabled telephony. For the men who arrived at what is now McMurdo Station Jules Madey was a 16-year old ham radio operator in 1956 when he read about the Antarctic expedition. The Clark, N.J., teen and his 13-year old brother, John, were radio-control-airplane enthusiasts when they learned a person could increase flying capabilities by operating on the ham radio frequencies. Studying together to learn the Morse code, they both got their ham licenses in 1954 and soon realized that talking to people around the world via ham radio was as much fun as flying airplanes. With the encouragement and help of their parents, they soon had a 110-foot tower in their back yard, enabling a better reception than most operators in the world had at that time. Jules also hooked up a telephone to the radio that allowed him to make phone patches. “I’d be in the basement doing my homework with the radio on when I’d receive a radio call from McMurdo, South Pole “Monty would give me the phone number and I’d place the collect call. The first time I placed the call, no one knew who this Jules kid was, but after the first time they eagerly would accept the collect call being placed by m.” Talking over a ham radio takes getting used to, Jules said. “I would have to explain to the person how to say ‘over’ when they had finished speaking. I had to listen to all the conversations because I had to switch the radio from transmit to receive after each speaker. It got to where I felt I knew these men and their families pretty well.” “Jules was a very mature teen,” recalls Tom “Monty” Montgomery, now of Clearwater, Fla.. “I was a 30-year old married radioman with three children when I first arrived in Antarctica. My wife and children were living in Martha’s Vineyard, and I remember very well the time Jules put a call through to her for me.” Disney studios even got involved, filming a ham call from Monty in McMurdo to Jules in New Jersey, who patched the call through to Monty’s wife. Ham radios most frequently operate on Federal Communications Commission The Madey boys had also rigged up a radiofax machine, allowing them to transmit scientific data as well as photos. Jules recalls, “A typical 8x10 photo took about 20 minutes to send in those days.” Montgomery says Jules ended up patching through the majority of calls for the Deep Freeze men because he had a better set-up than most people had at that time. “He had a huge antenna, so his reception was good, and he had a telephone hooked up for patching calls. Sometimes when I would be transmitting, I’d be picked up by someone in, say, California, but they didn’t have the capability of placing a phone patch. Jules did. It was just easier working with Jules than anyone else. I talked to him almost every night for over a year.”1 2 3 Next |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |