|

Birth of Antarctic scienceNew book documents how early explorers were driven by dual goals of discovery and researchPosted August 26, 2011

Many of the names are familiar to even the casual student of Antarctic history — Scott, Amundsen and Shackleton. Their stories are legend: The race to the South Pole between the methodical Norwegian and the brave but doomed British naval captain. Or Shackleton’s tenacious leadership and tale of survival when his ship Endurance was famously crushed by the sea ice in the Weddell Sea. But historian Edward Larson “This was a chance to right the record,” Larson explains of his new book, An Empire of Ice: Scott, Shackleton and the Heroic Age of Antarctic Science

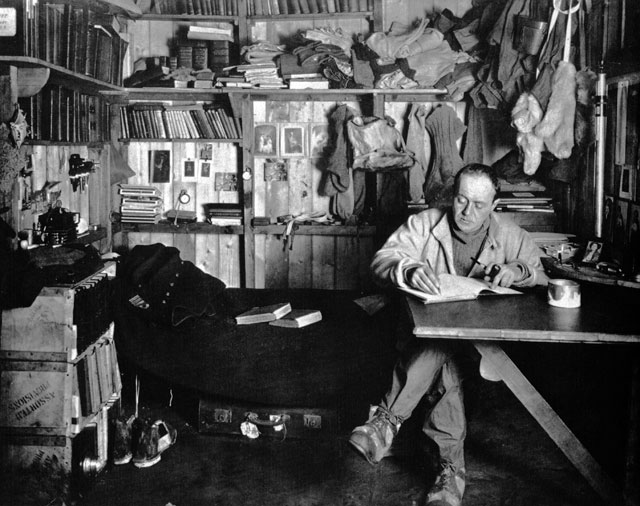

Photo Credit: Ed Larson

Author Ed Larson at Ernest Shackleton’s Nimrod Expedition Hut at Cape Royds.

“I think the history of science is important, because I think science is important. It’s how we understand the world. I want readers to know more about science and the history of science,” Larson says during an interview on a stop in Denver to promote the book. A professor of history who also holds the Hugh & Hazel Darling Chair in law at Pepperdine University The experience of following in the footsteps of Scott, Shackleton and the other explorers and scientists — from climbing the same volcano or observing the same penguin rookery a century later — proved invaluable for writing the book, according to Larson. “I couldn’t have gotten the feel for what they went through if I hadn’t experienced those places firsthand. If I hadn’t walked the Dry Valley, visited the polar plateau, or climbed Mount Erebus,” he says. “And the support staff was amazingly qualified in helping me do so at much less risk that the early explorers.”

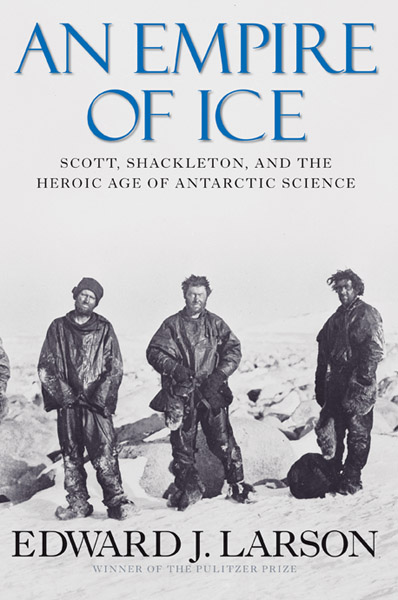

Ed Larson's new book examines the scientific motivations behind the early exploration of Antarctica.

An Empire of Ice focuses on what Larson considers the three major British science expeditions of the Heroic Age — Discovery (1901-04), Nimrod (1907-09) and Terra Nova (1910-13), each named after the expedition’s vessel —though he covers other expeditions as well, including the Norwegian one. He argues that the basis for today’s science programs in Antarctica began with the investigations pioneered by the British parties led by Scott (Discovery and Terra Nova) and Shackleton (Nimrod). In the book’s closing paragraph, Larson writes, “All three expeditions conducted significant research that, in fields ranging from climate change and paleontology to marine biology and glaciology, helped to shape the twentieth-century view of Antarctica and its place in the global system of nature.” The bulk of An Empire of Ice amply and ably makes the case for this interpretation by revisiting the diaries and journals of well-known personages like Scott and Shackleton, as well as examining the notes and scientific publications of all the principal scientists who joined, organized, or advised these expeditions. Men like the preeminent geologist Edgeworth David, who at age 50 joined Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition, arguably the most successful scientific expedition of the three. Or Raymond Priestly, whose thirst for adventure helped him through a winter in an ice cave during the Terra Nova expedition. He and others from the three expeditions would eventually piece together Antarctica’s geologic past, proving it was once connected to the other southern continents.

Photo Credit: James Murray

The four members of Ernest Shackleton's party that attempted to be the first ones to reach the South Pole during the 1907-09 Nimrod expedition. The men fell short of their goal but the expedition accomplished a great deal of science.

“It was just the right time to do this,” says Larson of the expeditions that helped usher in the modern age of science in Antarctica. Modern scientific techniques and theories were rapidly emerging at the time. The Darwinian theory of evolution motivated Edward Wilson to brave a sledging journey in the middle of winter to study the breeding ecology of emperor penguins. Wilson hoped to collect eggs and dissect the embryos to investigate an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. The five-week expedition turned into The Worst Journey in the World, a book penned by Wilson’s companion Apsley Cherry-Garrard. But the winter isolation suffered by Priestly and his mates along the coast in an ice cave, coated in grime from burning seal blubber, was probably the most grueling experienced by any of the science parties, Larson opines. “They’re out there solely to do scientific fieldwork. There’s no reason to be over there except for glaciology and geology,” he notes, adding that the deprivation broke some of the men, though not the indefatigable Priestly. “He’s the guy who, all the way back, collects rock samples. It was almost like he was enjoying it, which was really amazing. You couldn’t have had any more hellish conditions,” Larson says. Indeed, the science historian struggles to suggest an analogous time in history when men suffered so much for science. Scott’s willingness to devote resources and his best men to scientific discovery shows the race to the South Pole with Amundsen was more of a product of early 20th century hype than reality. Or as Larson writes in the book: “Unlike Amundsen’s, with its single-minded pursuit of the pole, Scott’s expedition had mixed goals.” In some ways, An Empire of Ice redeems Scott, whose “Tennysonian ideal” of a noble death fell out of a favor in a world rocked by the mechanized and senseless deaths of millions during two world wars, according to Larson. In fact, he says, Scott’s final letter about God and country undermined his own legacy, turning one of the world’s great science expeditions into a one-dimensional pursuit of glory against a superior opponent in Amundsen. In that context, judged harshly by historians, Scott is seen by many as something of a bumbler who took four other men to their deaths. “He misjudged the future,” Larson says of Scott’s conscious efforts to turn his sacrifice into heroic martyrdom on behalf of the British empire. “The story was always about science.” And that’s the well-told message that underlies Larson’s An Empire of Ice. NSF-funded research in this story: Edward J. Larson, Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |