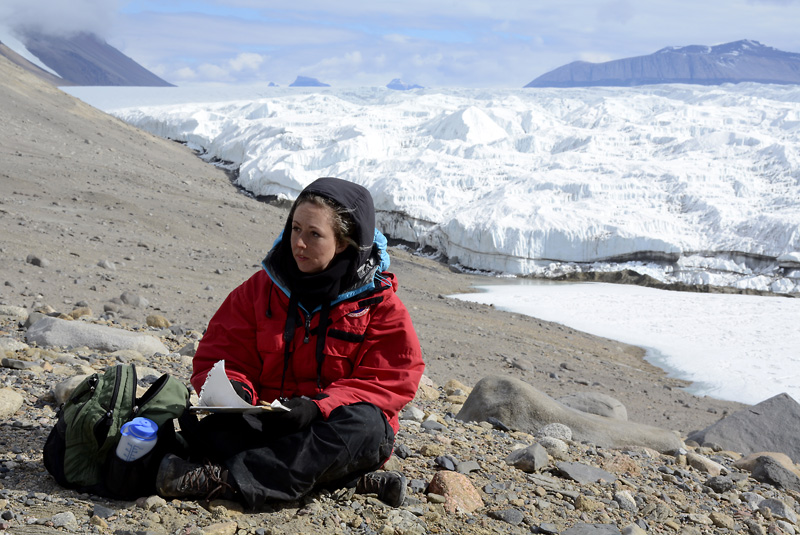

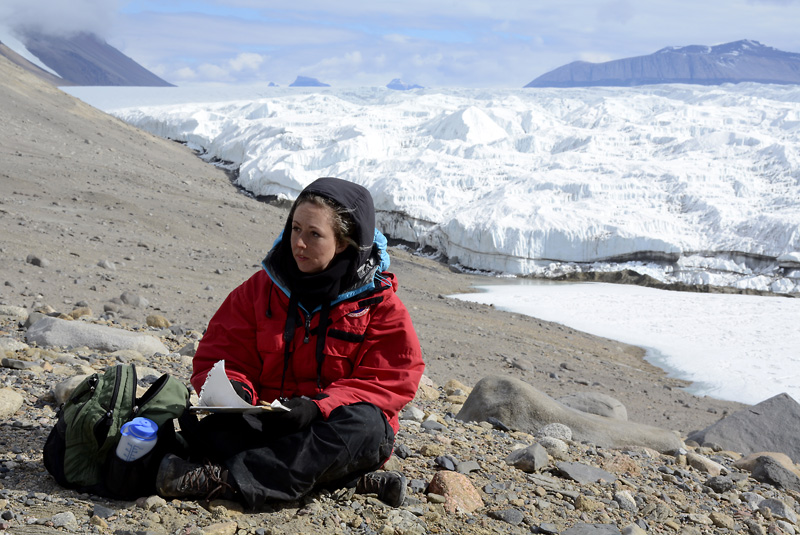

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

|

Artist Lily Simonson sketches in the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica. While her interests are usually in

small marine organisms, Simonson also sketched landscapes during her deployment under the NSF’s

Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

|

All creatures great and small

Artist Lily Simonson joins scientists in Antarctica to paint critters larger than life

By Peter Rejcek, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted June 29, 2015

The story of how an L.A. artist ended up scuba diving under the sea ice in Antarctica begins with lobsters.

Lily Simonson, even as a child, was fascinated with lobsters. Yes, even those held hostage in grocery store aquariums.

“I always made drawings from the time I was a little kid,” explains Simonson, an exhibited painter who spent more than three months in Antarctica diving and hiking across its varied seascapes and landscapes as part of the National Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

“I was always into natural illustration,” she adds during an interview at McMurdo Station where she had also set up an ad hoc studio to paint when not doing fieldwork.

Eventually, as her artistic career took shape in college, she found a new obsession – moths. Their frenzied behavior and lack of self-preservation seemed to parallel human hysteria, she explains. And they had a furry quality to them that she also appreciated.

Photo Credit: Alasdair Turner

Lily Simonson collects a critter, which she collected while scuba diving in Antarctica, out of the McMurdo Station Crary Lab touch tank to sketch.

Moths and lobsters: The two couldn’t seem further apart, except as seen through the lens of an artist. And then Mother Nature – and some intrepid scientists – nudged Simonson in a new direction, a moment she refers to now as “transformative.” Several friends sent her messages regarding a news article about the discovery of a deep-sea dwelling critter called a yeti crab.

The article described the creature as akin to a lobster but with the fur of a moth. “I became instantly fascinated by it,” Simonson says.

So much so that she flew to Paris to meet the yeti crab in person – and eventually got to know Danièle Guinot, one of the researchers behind the discovery.

“We were totally kindred spirits, and I started to see all of these parallels between art and science,” Simonson says. “One of the many parallels of art and science is to observe external phenomena and make sense of it.”

The yeti crab lives a bizarre existence near fissures in the seafloor from where geothermally heated water vents. The ecosystem is so far removed from the sun that the foundation of its food web revolves around chemosynthetic organisms that get their energy from chemical reactions rather than photosynthesis.

The metaphors that lived on her supersized canvases of moths and other invertebrates seemed less interesting than the backstory of the yeti crab.

“This stuff is so much weirder than I can impose on what I’m painting. Truth really is stranger than fiction,” she notes.

Simonson had no science background. She holds an MFA from UCLA and a BA from UC Berkeley. But that didn’t deter her from pursuing this budding interest to explore the intersection of art and science.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Lily Simonson, right, prepares for her first dive in McMurdo Sound with diver Rob Robbins.

Eventually, her collaborations with scientists would move out of the studio and lab and into the field, where she accompanies researchers on expeditions to see firsthand where the discoveries are made. One of her first trips was on the research vessel Melville, which was studying deep-sea fauna.

Every day, deep sediment cores and trawls along the seafloor would bring up a menagerie of bizarre invertebrates. Each day Simonson would use some of the muddy sediment as her paint and a wall of the ship van on the deck as canvas to draw one of the animals that were brought onboard, from polychaete worms to octopi.

“I really loved fieldwork and helping with fieldwork,” she says. “When you’re in the trenches of science and discovery, I think it makes the paintings that I then make a lot more interesting. I get a richer understanding of what’s being studied and how it’s being studied.”

The yeti crab and its newly discovered cousins would eventually play a key role in getting her interested in altogether different fieldwork. A young scientist named Andrew Thurber had discovered a species of yeti crab that seemed to “dance” around hydrothermal vents near Costa Rica.

When Simonson contacted Thurber, he told her about the primary focus of his research at the time – invertebrates in Antarctica – and the stunning marine world that exists below the sea ice. He invited her to come and see it for herself, as well as told her about the existence of the NSF Artists and Writers Program, a highly competitive but unfunded fellowship that supports the arts by allowing a select few to work on the Ice each year.

“The idea hooked me in,” she says.

Previous 1 2 Next