|

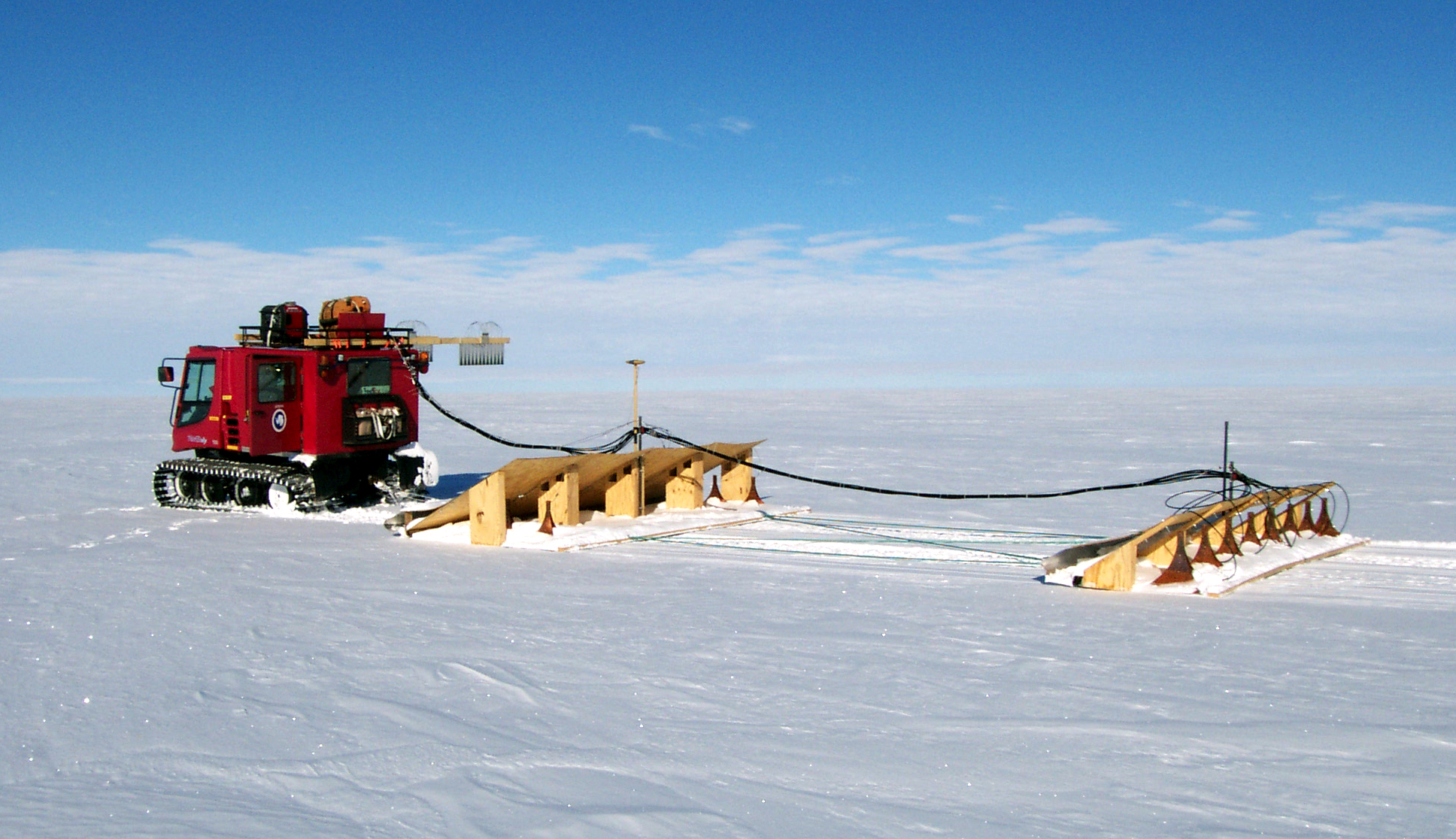

CReSIS prepares for large science campaign in 2008-09The CReSIS researchers and engineers don’t just design and build all of the high-tech instruments. They take them into the field as well.This year a small team mainly from Penn State is working out of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet Divide camp and near one of the continent’s fast-moving rivers of ice, the Thwaites Glacier. Their work involves using seismic sensors to image the ice and what is below, as well as to install GPS receivers on the glacier to study its flow dynamics. The airborne sensors can do some of that work, but the seismic waves can penetrate well below the ice to determine what’s happening underneath, according to Anandakrishnan. “The ice is actually sliding over whatever is beneath it, if it’s warm enough … so it’s sliding over something and we need to know what that something is,” he explained.

Photo Credit: Patrick Olmert/NSF

CReSIS Director Prasad Gogineni, far right. and Associate Director of Administration Stephan Ingalls, second from right, attend an NSF budget workshop. Next year, CReSIS will really roll, with a bigger seismic campaign and an airborne radar sweep across hundreds of kilometers of the West Antarctic ice sheet. Gogineni said CReSIS would put about 20 scientists in the field for upward of two months. “So you’ll have all of the information that is required to understand what is happening in this area,” he said.

Correcting the modelsAll of this work funnels down to solving the current deficiencies in the ice sheet models. Kees van der Veen, an associate professor at KU, is one of the CReSIS researchers heading up the modeling and analysis efforts.Van der Veen explained that the rapid changes in the ice sheets of Greenland and West Antarctica shouldn’t be happening, based on the numerical models scientists have developed to predict such occurrences. “The existing models predict ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica to respond pretty slowly to climate forcings,” he said. The nonlinear changes mean that the sea level projections from the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change are also probably out of tune. The floating ice shelves serve as proverbial corks in the bottle, slowing the discharge of ice from the ice sheets. It’s likely that as the ice shelves disintegrate, as those corks break apart, ice will spill out more rapidly. “In the [Antarctic] Peninsula, that’s what we’ve seen after the break up of the [Larsen B] ice shelf,” van der Veen said. The ice sheet models of the time weren’t even close in predicting what would happen in the aftermath of the 2002 event, according to Andandakrishnan. “The glaciers that fed into Larsen B sped up by huge numbers – in one case, as much as a factor of eight speed-up. And that’s just something that the models would not have predicted,” he said. “If that is the case, then we’re missing some fundamental physics in these models, or some fundamental interactions between the oceans, the ice shelves and the glaciers.” Van der Veen said it’s not clear whether the engine driving the rapid loss is located only at the edges of the ice sheet. One thought is that geothermal heat underneath the ice plays a role in speeding the ice toward the ocean. (See related CReSIS story on geothermal flux.) The KU professor said to improve the models, scientists need to collect an array of measurements on several glaciers, such as how fast the ice is moving, its geometry, the shape of the bedrock below, and whether or not water is present underneath. “That’s really what CReSIS has taken as its marching orders – to put better bounds around [the models], so as temperature rises, as oceans start to warm, you’ll have some notion as to what ice shelves are going to do and how much faster that inland ice is going to flow,” Anandakrishnan said. NSF-funded research in this story: Prasad Gogineni, University of Kansas-Lawrence, www.cresis.ku.edu |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |