Photo Credit: Jim Elliot/British Antarctic Survey |

The British Antarctic Survey captured live images of the Wilkins Ice Shelf beginning to collapse. The ice shelf is "hanging by a thread" and most scientists believe it is only a matter of time before it disintegrates. |

Breaking up

Wilkins Ice Shelf disintegration becomes part of climate change pattern in West Antarctica

By Peter Rejcek, Antarctic Sun Editor

Posted April 18, 2008

The spectacular disintegration of a large chunk of the Wilkins Ice Shelf off the Antarctic Peninsula last month may be part of an accelerating pattern of climate change in the region.

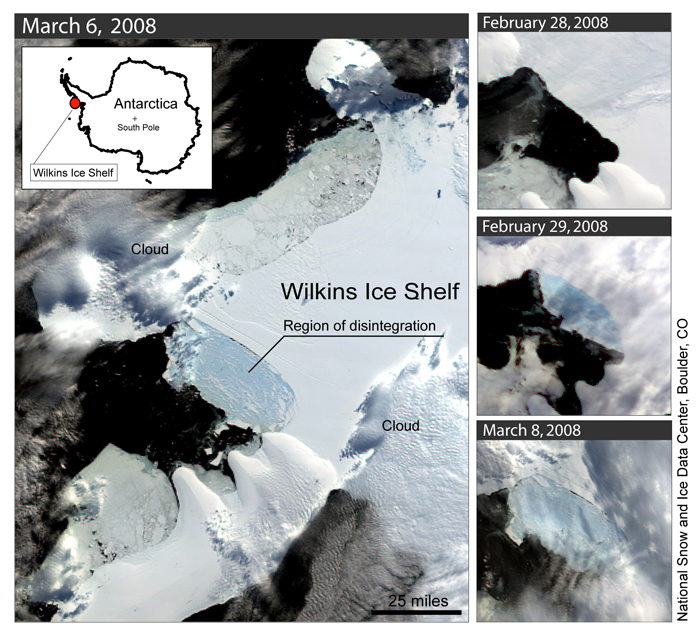

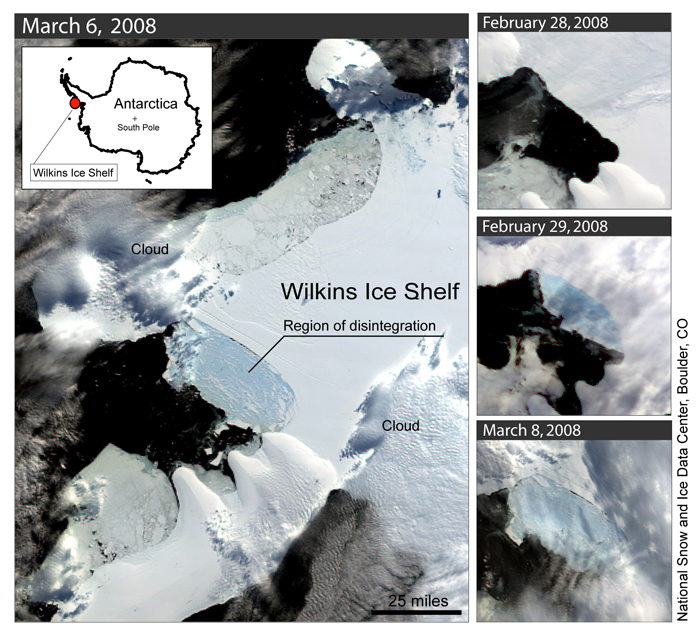

That’s the conclusion that scientists are drawing after more than 400 square kilometers of ice sloughed off the southwestern front of the ice shelf. A series of satellite images processed at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colo., showed the edge of the shelf crumbling and disintegrating in a pattern that has become characteristic of climate-caused ice shelf retreats throughout the northern Peninsula area, according to NSIDC scientists.

“We were all surprised — but not really surprised — about the Wilkins collapse,” said Hugh Ducklow, principal investigator for the Palmer Long Term Ecological Research (PAL LTER) program, funded by the National Science Foundation.

The shelf is located south of the U.S. Antarctic Program’s Palmer Station, around which scientists have conducted a long-term study of the ecosystem for more than 15 years. They recently proposed to extend the study area farther south, to Charcot Island, where the Wilkins Ice Shelf is buckling.

“It is in the new, extended southern part of our study area, and it would seem to suggest that warming is reaching there,” said Ducklow, a marine ecologist and co-director of The Ecosystems Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass. “We have not seen much evidence that there have been ecological changes in that area, at least not to the degree we have documented around Palmer Station.”

The Antarctic Peninsula has arguably experienced the most dramatic rise in temperature over the last 50 years. NSIDC reported that temperatures have climbed 0.5 degrees Celsius each decade. PAL LTER scientists have said the overall increase is about 6.5 degrees Celsius in the winter since the 1950s, rising more than five times faster than the global average.

In addition, the life cycle of winter sea ice since 1979 has dropped, on average, by three months per year around Palmer Station, meaning it forms later and melts earlier. Summer sea ice is virtually non-existent in the area, and perennial sea ice has also all but disappeared.

“The sea ice plays a big role, and may have been the thing that triggered [the ice shelf collapse] this year,” noted Walt Meier, a scientist with NSIDC.

Photo Credit: NSIDC

Satellite images show the progression of the ice shelf collapse.

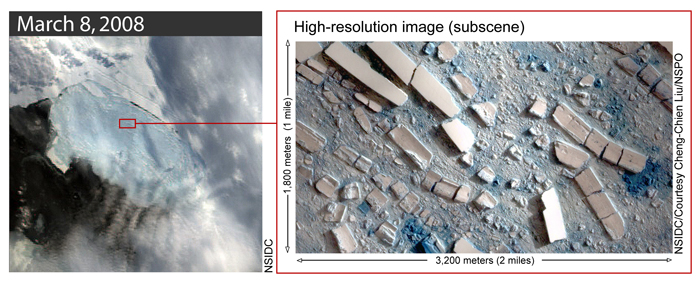

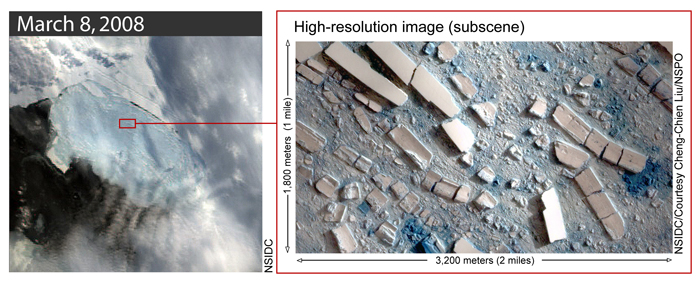

Photo Courtesy: NSIDC

A high-resolution satellite image from the Taiwanese space program shows the ice shelf break-up in startling detail.

Meier explained that the sea ice serves as a buffer between the ice shelf and ocean waves, which can pummel an unprotected ice shelf, causing it to flex, particularly if it has been weakened by melt ponds, pools of open water on the ice surface that absorb rather than reflect heat.

“[Sea ice] acts as a damper on any ocean waves,” Meier said. “This year we almost had no sea ice for a significant amount of time during the summer along the Wilkins. That allows ocean waves to build up.”

The approach of winter and a thin band of ice only a few kilometers wide likely saved the rest of the shelf from immediately collapsing. But it’s probably only a matter of time before Wilkins, an ice shelf roughly the size of Connecticut, completely disintegrates. The question is when.

“That’s going to depend a lot on what the conditions are next summer. If we have another summer like this year where the sea ice went out and that area is exposed, it certainly could be next summer. We did see a lot of melt ponding; we did see things on the verge of breaking up,” Meier said.

“I think we can say in the coming years, we’ll likely see that collapse,” he added.

The Wilkins disintegration won’t raise sea levels because it already floats in the ocean, and few glaciers flow into it. However, NSIDC scientists and others note that the collapse appears to be part of a pattern, and additional ice shelves in the region may be at risk. Several have retreated in the past 30 years, with six of them collapsing completely — Prince Gustav Channel, Larsen Inlet, Larsen A, Larsen B, Wordie, Muller and the Jones ice shelves.

“It’s an indication that things are continuing to happen, and we can maybe expect it to accelerate in future years with other ice shelves,” Meier said.

NSIDC lead scientist Ted Scambos first discovered that the ice shelf was collapsing in March. He then alerted colleagues around the world, initiating an international scramble to focus attention on the break-up. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) responded by sending out a Twin Otter aircraft over the ice shelf and taking video footage. Taiwanese scientists also assisted, taking high-resolution color satellite images of the area using their country’s Formosat-2 satellite.

“It’s certainly something that draws scientists’ attention. It was a really nice case of collaboration,” Meier said. “These types of things are definitely international efforts. No one group has all the tools and resources to do this at once.”

The PAL LTER scientists are now even more eager to head south. “The ice shelf breakup indicates the speed at which things are beginning to change, and the urgency to get into the region and start making the kinds of observations and experimental studies we have been conducting farther north over the past 15 years,” Ducklow said.

There may even be an upside should the Wilkins disintegrate in the near future, he noted: “One possible advantage of the Wilkins breakup is that we might be able to get a little closer in, a bit farther down than before.”

NSF-funded research in this story: National Snow and Ice Data Center; Hugh Ducklow, Marine Biological Laboratory.