|

Moving experiencePOLENET will monitor bedrock beneath ice sheets to learn more about post-glacial reboundPosted June 13, 2008

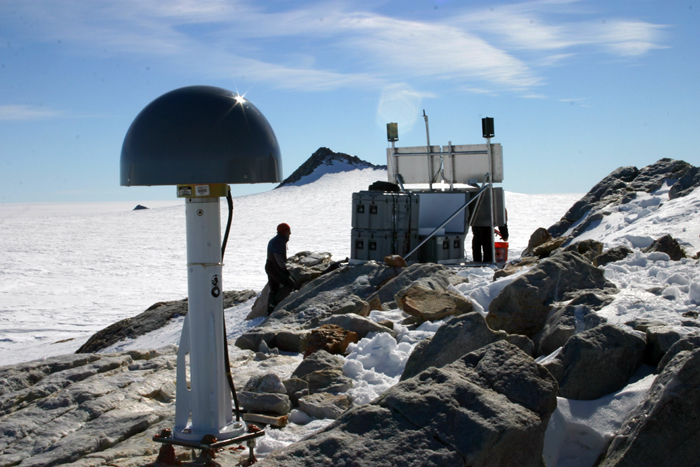

Terry Wilson’s office at Ohio State University seems pretty typical of a college professor, especially one who splits her time teaching the fundamentals of geology to undergraduates while managing one of the largest and most ambitious projects of the International Polar Year (IPY). Stacks of papers sit in relatively neat piles on the floor, leaving just enough of an aisle to maneuver in and out of the office. Various filing cabinet drawers are pulled out to their maximum extent, revealing cramped and stuffed folders. The sheer weight of the paperwork seems enough to cause a dimple in the earth that supports her office. Should that material suddenly blow away, vanish in a freak windstorm, the ground underneath would eventually rebound to its original state, slowly sighing in relief as the burden of weight goes away. In Antarctica, where the weight of its mighty ice sheets have squashed the earth’s crust below, Wilson and an international team of scientists are studying a real phenomenon called post-glacial rebound. The work is part of an ambitious project, called POLENET, for Polar Earth Observing Network. POLENET has many goals, from helping to predict sea level rise to learning more about the earth below the crust and down to its core. It’s one of the flagship projects of IPY The $4.5 million project, led by scientists with the Byrd Polar Research Center The effort began last austral summer in Antarctica, and will continue through the 2011-12 field season. Collaborators include scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, New Mexico Tech, Penn State, University of Memphis, University of Texas Institute for Geophysics and Washington University. On the reboundThe POLENET GPS receivers aren’t like a handheld unit that you might use to set a waypoint to your favorite backcountry trail or to navigate city streets. These instruments can measure with millimeter-level accuracy, as one important experiment measures the rate at which the bedrock of the continent moves vertically. How can the earth move in such a way? Well, there’s a lot of ice in Antarctica, but there was even more during what’s known as the last glacial maximum, when ice sheets draped across parts of Europe and North America in the northern hemisphere and Chile and Argentina in the southern hemisphere. The ice was at its maximum extent about 20,000 years ago, then began to shrink. The ice sheets never disappeared from Antarctica, of course, but they lost a lot of mass during the current interglacial period, well before the Industrial Revolution kicked temperature rise into high gear. How much ice has disappeared? Well, that’s what Wilson and her team hope to find out as they measure the rate of rebound now that all that weight is gone. As you might imagine, it’s a slow, lengthy process. “We’re looking for a long-term signal that shows us this rate of uplift due to ice mass loss since the last glacial maximum,” explained Wilson, associate professor of Earth sciences at Ohio State. Elastic responseBut there are more forces at work than this ancient signature. The TransAntarctic Mountains DEFormation (TAMDEF) “People with GPS measurements have been able to measure the deflection of the surface from adding snow in the winter and removing snow in the summer,” Wilson said. In fact, the earth at places such as the Amazon Basin reacts strongly to this elastic effect, as a sizable portion of South America sinks when the river floods and then rises more than 5 to 6 centimeters when the waters recede each year. Many scientists, citing satellite data, believe West Antarctica is losing ice almost as quickly as Greenland because of global warming. The crust below the ice sheet should have an elastic response to that massive, modern evacuation of ice. The idea is if you can capture the rate of elastic response, a relatively short-term event, you can get a true measure of the size of the ice sheet and how much mass it is losing. That would finally put a realistic number on future sea level rise as Antarctica continues to shed weight faster than a contestant on TV’s “The Biggest Loser.” “It’s kind of serendipity in a way that we’re getting this array of instruments out in time to start recording some of those dynamic changes, particularly in West Antarctica and up toward the Antarctic Peninsula, that are surprising everyone,” Wilson said.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |