|

Linking extinctionsNSF-funded scientist says major die-offs related to ebb and flow of sea levelPosted August 15, 2008

Scientists who play the geologic version of the board game Clue when trying to identify the likely suspect for past mass extinctions on the planet have a new rule to consider. A study published online June 15 in the journal Nature suggests the consistent ebb and flow of sea level is the common link to mass extinction over the last 500 million years. NSF Press Release

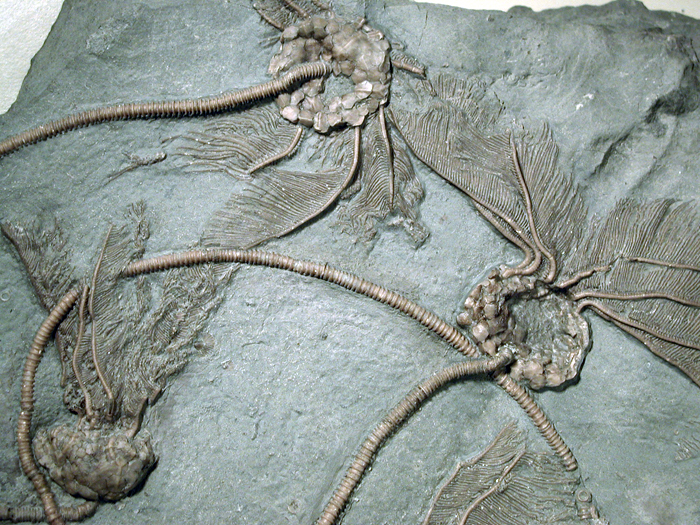

“The expansions and contractions of those environments have pretty profound effects on life on Earth,” said Shanan Peters, a University of Wisconsin-Madison assistant professor of geology and geophysics and the author of the new Nature report, in a news release from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Changes in ocean environments related to sea level exert a driving influence on rates of extinction, which animals and plants survive or vanish, and generally determine the composition of life in the oceans, according to Peters. “Impacts, for the most part, aren’t associated with most extinctions,” he said in the news release. “There have also been studies of volcanism, and some eruptions correspond to extinction, but many do not.” Since the advent of life on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, scientists think there may have been as many as 23 mass extinction events, many involving simple forms of life such as single-celled microorganisms. Over the past 540 million years, there have been five well-documented mass extinctions, primarily of marine plants and animals, with as many as 75 to 95 percent of species lost. The study doesn’t dismiss other influences, such as killer asteroids or massive volcanic eruptions, but Peters said his study provides a common link to mass extinction events over a significant stretch of Earth history. “The major mass extinctions tend to be treated in isolation by scientists,” Peters said. “This work links them and smaller events in terms of a forcing mechanism, and it also tells us something about who survives and who doesn’t across these boundaries. These results argue for a substantial fraction of change in extinction rates being controlled by just one environmental parameter.” Matthew Saltzman, an associate professor at The Ohio State University’s School of Earth Sciences, whose recent work looks at climate change related to carbon cycling as one factor in the Permian-Triassic (P-T) extinction, expressed some skepticism that one environmental factor links all mass extinctions. “[Mass extinctions] are complex problems,” he said, “but that’s what makes it interesting.” NSF-funded research in this story: Matthew Saltzman, The Ohio State University, Award No. 0636824 Return to main story: The Great Dying. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |