|

Antarctica's Holy GrailProject seeks best spot to drill for sediments dating back to greenhouse-icehouse transitionPosted October 10, 2008

Pirates had it easy. A big “X” marks the spot on a yellowed, stained map of buried treasure. Just dig there. Not so easy for Antarctic scientists who want to pinpoint a location for drilling into ancient sediments that will give them a window into what the climate was like when the frozen continent was closer to a greenhouse than an icehouse. Stephen Pekar Education and Outreach

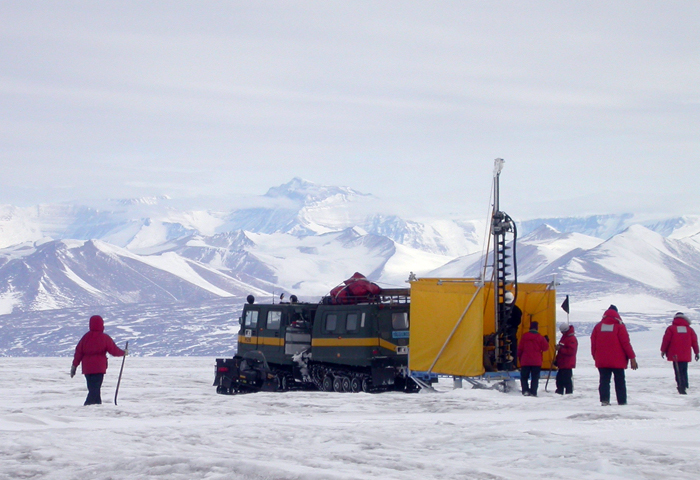

“What’s so important about this is that we don’t have any core sediments from the greenhouse world from Antarctica,” Pekar explained only a few weeks before leaving for McMurdo Station The oldest sediment cores drilled in Antarctica come from an Antarctica New Zealand Pekar’s team, which includes Marvin Speece An International Polar Year The idea is that by understanding the past, researchers can better predict how Antarctica’s ice may react as the current greenhouse world continues to heat up. “This area of the Ross Sea has been piling up sediment layers for many tens of millions of years, literally a tape recorder of geologic events in the area, which include continental erosion, volcanic eruptions, tectonic movements, biologic activity, and the most important of them all for this study: ice sheet movements in East and West Antarctica,” noted Tom Wagner, program manager of Antarctic Earth Sciences in the National Science Foundation’s Office of Polar Programs To find the proverbial “X” the team will use geophysical instruments to collect data about the layers of sediments underneath the sea ice and seawater below. One method includes stringing a line of geophones (basically highly sensitive microphones) across the ice. Sound waves reflect off the sediment layers below the seafloor, which the geophones pick up and transmit to a computer in a heated building mounted on a sled. This raw seismic data of the ocean floor, when filtered by the scientists, will give them a good map upon which to base a proposal for further drilling. “We are hoping that the seismics will give us data that says, ‘Yes, there’s more greenhouse sediments down there,’” Pekar said. The scientists already know that the sediments in the area are close to their target date based on the CIROS project. In fact, the New Harbor project will image rock layers close to the site of one drill hole, CIROS-1. “If we see more sedimentary layers below that, we know they’re greenhouse age sediments,” Pekar explained. The CIROS-1 data, while incomplete, does cross the greenhouse-icehouse boundary, going back about 36.5 million years into the Eocene epoch, according to Pekar. There was some evidence of glaciation in the CIROS-1 core. “It was surprising to see some glaciation, even if it’s temperate — small, tidewater glaciers — there seems to be some evidence for that,” Pekar said. As the icehouse world took over, the cooling trend turned increasingly cold, until tundra-like conditions occurred about 8 to 10 million years into the icehouse world era, he added. Competing hypotheses proclaim the continent was virtually ice free at the greenhouse-icehouse boundary, while at the other extreme some believe the ice sheets were quite formidable, though smaller than today. “We’re just keeping our minds open, and having multiple hypotheses, and let the data come in and tell the story,” Pekar said. “The big transition occurs across 34 million years, when we go from small or nonexistent ice sheets to large ice sheets that were moving across where CIROS-1 is today.” The field plan is to cover about 45 kilometers in two separate traverse lines that will cross, one toward the Taylor Valley and the second toward the Ferrar Valley in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Pekar estimated the team would be on the sea ice up to 40 days, hopefully arriving back in McMurdo before Thanksgiving. “It’s much slower than marine seismics, where they’re moving about [8 kilometers] an hour. We’ll be lucky if we can get 3 kilometers a day,” he said. Wilson will oversee the gravity measurements for the expedition. Gravity allows the geologists and other scientists to look at deeper structures than the seismics can image by measuring the gravitational pull — the denser the rock, the greater the gravitational pull. “These instruments are incredibly sensitive to any minute changes in the gravitational pull,” Pekar said. “If you have … denser rock below, it will pick up that extra bit of gravity. It can’t give us a clear image of what’s down there, but it does give us overall gross features of what the rock looks like deeper down.” Offshore New Harbor is one of three sites the ANDRILL program has targeted for further drilling. A second site, Mackay Sea Valley, northeast of Cape Roberts in the Ross Sea, possibly contains extremely young sediments, in the thousands of years. A proposal for drilling has been submitted for a site called Coulman High, located east of Ross Island, where McMurdo Station sits. The age of the rock layers there is something of a wildcard, but certainly in the tens of millions of years. “It’s exciting in that it’s discovery of the unknown,” Pekar said. NSF-funded research in this story: Stephen Pekar, Queens College, Award No. 0732796 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |