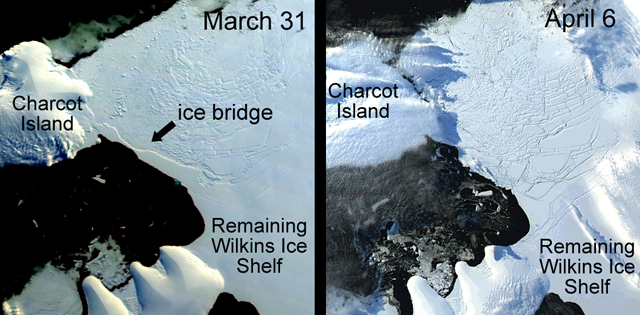

Wilkins Ice ShelfBreak-up continues in April with loss of ice bridge, new ice bergsPosted May 1, 2009

Going, going … but not quite gone. The disintegration of an ice bridge linking the Wilkins Ice Shelf between two islands on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula isn’t likely to cause the remainder of the floating chunk of ice to break up this year, according to the lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Ted Scambos At that time, about 400 square kilometers of ice sloughed off the southwestern front of the ice shelf. The Antarctic winter offered no relief, as the shelf continued to fracture and pieces of ice continued to chip off, including another 160 square kilometers along the ice bridge. The final shattering of the ice bridge in early April — at that point only about 500 meters wide and 40 kilometers long — garnered worldwide attention. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton Antarctic Sun coverage of Wilkins Ice Shelf

More recently, the European Space Agency (ESA) reported this week To a certain degree, Scambos explained, the importance of the bridge had diminished by the time it broke up. A line of fractures had already appeared south of the bridge, connecting various islands and ice rises, which are likely to become the new front of the ice shelf after the current break-up ends, he said. That’s where the bergs are now dropping into the ocean. “When the ice bridge collapsed, these rifts re-activated,” he said prior to the new activity reported by ESA. “But it doesn't appear that there are new rifts forming even further into the shelf. I don't think we’ll see a complete break-up of the remaining southern two-thirds of the Wilkins this year, but we will continue to watch the evolution of these rifts — they’re likely to grow, and climate is likely to push the system towards more change in the years to come.” The Wilkins Ice Shelf is located off the southwestern Antarctic Peninsula, arguably the fastest-warming region of the Earth. In the past 50 years, the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed by 2.5 degrees Celsius, according to the NSIDC. In the early 1990s, when it first began to lose ice, the Wilkins Ice Shelf had a total area of 17,400 square kilometers. Between 1998 and 2008, it dropped in area to roughly 13,680 square kilometers, about the size of Connecticut. Now, in just the last year, it’s lost another 3,600 square kilometers before the iceberg calving began. Scambos said he did not expect a total collapse just yet. “This winter we'll get an idea of how much the loss of the bridge, and the new shape of the ice front, means to the stability of the remaining Wilkins. But I think it will be several years before the rest of the Wilkins breaks up,” he said. “I think sections of it nestled in southern bays will be around for decades, but it would be much smaller.” The ice shelf floats on the ocean, so it won’t contribute to sea-level rise. The concern about the loss or thinning of ice shelves is that the glaciers that usually feed into them will increase speed, and that’s when sea level begins to creep up. “But the Wilkins is rather odd,” Scambos noted. “It is mostly fed by snowfall directly upon it. There are a few glaciers in the far south, but really, I would not expect a dynamic, interesting signal from this.”1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |