Dress rehearsalFieldwork to prepare for major project in 2011-12 makes milestone, discoveryPosted December 25, 2009

Scientists conducting a “dress rehearsal” for deployment of an instrument through an ice shelf into the ocean below learned quite a bit about the system during a weeklong field test in Antarctica — making polar history and an unexpected discovery along the way. “I’m really glad we had this opportunity to practice our techniques,” said Robert Bindschadler Bindschadler is the principal investigator for a project jointly funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) The concern is that the faster the ice flows, the faster sea level could rise, flooding low-lying areas and coastal regions around the world in the coming century. A recent report from the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Bindschadler and his team believe warmer ocean water is responsible for thinning the ice shelf. They want to send several instruments down into the cavity below the ice shelf to understand exactly what’s happening. The operation, scheduled for the 2011-12 field season, will require drilling a 500-meter-deep hole into the ice shelf. They will then send an instrument, a specially designed ocean profiler, down the hole to measure various ocean properties. The profiler will move vertically up and down on a cable through the entire water column to measure and monitor the complex ocean currents. [See related article: Pine Island Glacier.]

Photo Credit: Robert Bindschadler

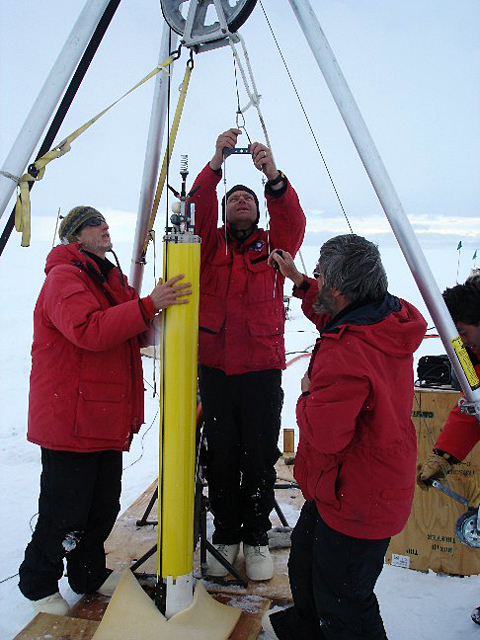

Scientists prepare to send an instrument to measure the ocean through an ice shelf.

This season’s field test eventually brought together six members of the team to an area on the Ross Ice Shelf Bindschadler said the team accomplished its goal of sending one ocean profiler though the ice shelf at Windless Bight, about 200 meters thick, using a hotwater drill that melts a hole in the ice. He said it was the first time scientists have deployed an ocean profiler beneath an Antarctic ice shelf. Tim Stanton’s Ocean Turbulence Laboratory in the Oceanography Department at the Naval Postgraduate School “The deployment with [colleagues] Martin Truffer and Dale [Pomraning] was very successful, and confirmed that the small team of people could melt the 200-[meter]-deep, 20-[centimeter]-diameter holes and deploy the profiler down and have it survive, communicate and operate,” said Stanton via e-mail from Christchurch, New Zealand, shortly after leaving the Ice. Unfortunately, the team lost communications with the profiler shortly after breaking up their field camp. Additional attempts to fix the problem haven’t been successful, but Stanton said the team has several theories about the technical failure as well as how to fix it. They did confirm on a return trip that the profiler was still below the ice shelf. A new science mission?Video shot from a camera first lowered down the hole returned “stunning” imagery, according to Bindschadler, including a shrimplike amphipod. Stacy Kim

Photo Credit: Robert Bindschadler

Martin Truffer from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, leads the hotwater drilling component of the project.

“[It’s] very, very amazing to find indications that higher life is abundant enough that far back under the permanent ice that Bob found [two] separate pieces of evidence for it,” said Kim, whose own field team is in its third year testing an underwater robot capable of diving hundreds of meters deep to explore the benthic, or seafloor, ecosystem. [See previous articles: SCINI in the Sound and Fitting in.] “That probably sparked with what will be a collaboration between us,” Bindschadler said. “She’s interested in the biology, and we discovered biology that invites further analysis.” Kim has been at McMurdo Station since August running her robot SCINI (Submersible Capable of under Ice Navigation and Imaging) “I strongly hope that we can develop collaborative work,” Kim said by e-mail from McMurdo shortly before leaving. “I would be very interested in doing seafloor surveys of benthic communities under the permanent ice shelf, and maybe a spatial survey would be of use to Bob in conjunction with his temporal data sets.” Lessons learnedWhile the Windless Bight field test was successful, the work proved to be challenging — and instructive. For instance, the researchers learned to cover the drill hole at all times. An object dropped down the hole is lost forever, and can foul up the hole, making it unusable. That happened once, Bindschadler said. Of course, the infamous Antarctic cold and wind — the term “windless” being relative in this case — makes it more difficult to do even simple tasks. The operation also required long hours, as once you begin a hole you’re committed or the ice will close back up, Bindschadler said. “It was an extremely productive week,” he noted. “We discussed what the improvements could be almost on a daily basis.” Now the team must play the waiting game. The surface of the ice shelf is too rugged for planes to land on, so support crews must build two field camps for the field program, including one for helicopter operations to the ice shelf itself. [See previous article: Byrd Camp resurfaces.] The team won’t be able to start work from their field camp at Pine Island until the 2011-2012 field season. “It’s extremely frustrating the pace at which the real prize is being held off,” Bindschadler said. “We’ll get there. The science demands that we get out to Pine Island. That’s where the answer to ice sheet stability lies, and we’re not going to get the answer anywhere else but underneath that ice shelf. The requirement that we get out there is still as clear and as urgent as it’s always been.” NSF-funded research in this story: Robert Bindschadler and Alberto Behar, Goddard Space Flight Center, Award No. 0732906

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |