Back in timePalmer LTER scientists monitor climate change across Antarctic PeninsulaPosted June 18, 2010

Hugh Ducklow The PhD from the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) His time machine is an ice-strengthened research vessel. The space is a 700-kilometer-long stretch of ocean along the western edge of the Antarctic Peninsula. The northern extreme of the region has warmed as quickly as anywhere in the world, ushering in a subantarctic climate and the types of critters that favor such conditions. Palmer LTER: Back in time

More stories about the January 2010 LTER cruise.

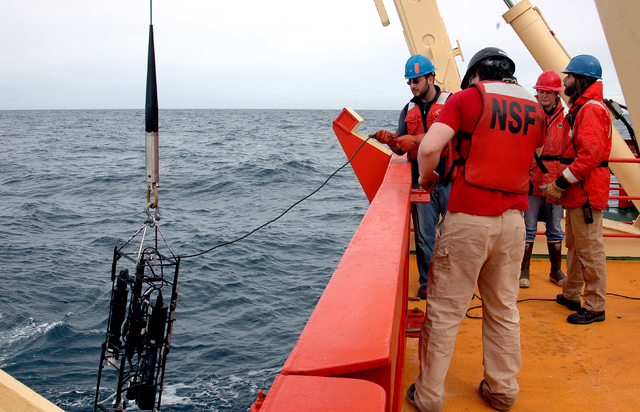

Flying south A shrinking problem Abundantly clear Without a trace At the southern end — near an island called Charcot, named after the father of a French explorer — Antarctica still exists. Sea ice persists throughout the summer, thick enough to slow the Gould down to 1 knot with its engines pumping at full power. The surface ocean is a frigid minus 1.8 degrees Celsius, kept from freezing only by the high salinity in the water. Once upon a time, the northern end around Palmer Station “Going farther south we think of as going back in time, and trying to find conditions of what this region was like before it started to warm very much,” explained Ducklow, director of The Ecosystems Center “We want a reference area where we can see where the ecosystem may be like before sea ice loss became so extensive,” added Ducklow, seated in the ship’s chief scientist office, with a little time to kill as the Gould makes the four-day trip from Punta Arenas, Chile, to Palmer Station on Anvers Island. After a brief port call to offload cargo and exchange passengers, the ship will begin a 28-day study of the region. It’s a journey that PAL LTER scientists have made 17 previous times since 1993. The peninsula is one of 26 long-term research sites funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Nearly 20 years ago, when the PAL LTER was first conceived, the big question in polar oceanography was how the marine ecosystem responds to the rhythm and changes in sea ice from year to year, according to Ducklow, a biological oceanographer. Sea ice is relatively thin ice that forms on the ocean surface, nearly doubling the size of the continent every winter and shrinking back each austral summer. The researchers were interested in answering basic questions about what role the ice played throughout the food web, from top predators like penguins, to small marine critters like krill, to the algae that bloom and float through the upper levels of the ocean. But by 1993, the cold and dry conditions that once dominated the northern end of the peninsula had been pushed aside by a warmer, more humid climate. Climate change was already under way. “It is fortuitous — it is completely fortuitous — that Palmer Station, in the middle of the peninsula, and currently the Gould, happen to be studying this area, at this time, in this century, when it’s one of the hotspots of global change on the planet,” Ducklow said. The penguin poster childThe poster child for climate change around the Antarctic Peninsula has been the Adélie penguin, one of three brushtail penguin species in the world. Its population has dropped from about 15,000 to 2,500 breeding pairs — spread out across about 20 islands near Palmer Station — over the last 30 years. “We’re using seabirds as monitors of change in the environment,” said Donna Patterson-Fraser, who has worked on the seabird component of the PAL LTER since the early 1990s and has watched the Adélie colonies decline. The islands, once stained pink from the krill-centric diet of the Adélies, are home to ever-dwindling pockets of the birds.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Kirstie Yeager walks among Adélie penguins on Humble Island near Palmer Station.

“Something is going to have to change for them to bounce back. I don’t see them bouncing back in my lifetime. It’s depressing,” she added. Most of the “birders,” led by Bill Fraser with Polar Oceans Research Group out of Montana, work from Palmer Station for the summer season, which lasts from about October to March, a relatively balmy time of the year with nearly 24 hours of daylight at its peak. It’s a long stretch of time over which the various bird species return to the islands to nest, lay eggs, and fledge chicks. The biologists pilot inflatable boats to the rock-strewn islands nearly every day, weather allowing, counting and monitoring the Adélies, gentoo and chinstrap penguins, brown and south polar skuas, giant petrels and other polar-loving seabirds. Not all are facing local extinction like the Adélies. For example, the gentoo, a larger, deeper-diving penguin, isn’t dependent on sea ice. Its flexibility in breeding and diet has helped it out-compete its smaller cousin. For instance, 20 years ago, there were no gentoos at Biscoe Point, a spit of land on an island once thought to be a peninsula of Anvers Island until the glacier retreated. Today, there are 2,500 breeding pairs on Biscoe. “They’re all dancing to a different beat,” Patterson-Fraser said of the seabirds. The Adélie decline is well known by now, a cautionary tale, the so-called canary in the coalmine. But the apparent ascendancy of subantarctic gentoos and chinstraps over Adélies is only one story of how the migration of a subantarctic climate along the peninsula is dramatically changing the ecosystem. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |