On the lineResearchers spend summer in deep-freeze to slice and dice WAIS Divide ice corePosted August 20, 2010

It’s midsummer in Denver, and the city has been baking under a heat wave for a couple of months. But in one small corner of the sprawling Denver Federal Center campus in the nearby suburb of Lakewood, about a dozen people are bundled up in thickly insulated Carhartt jumpsuits, wool caps, scarves and gloves. More Information

Related Sun story:

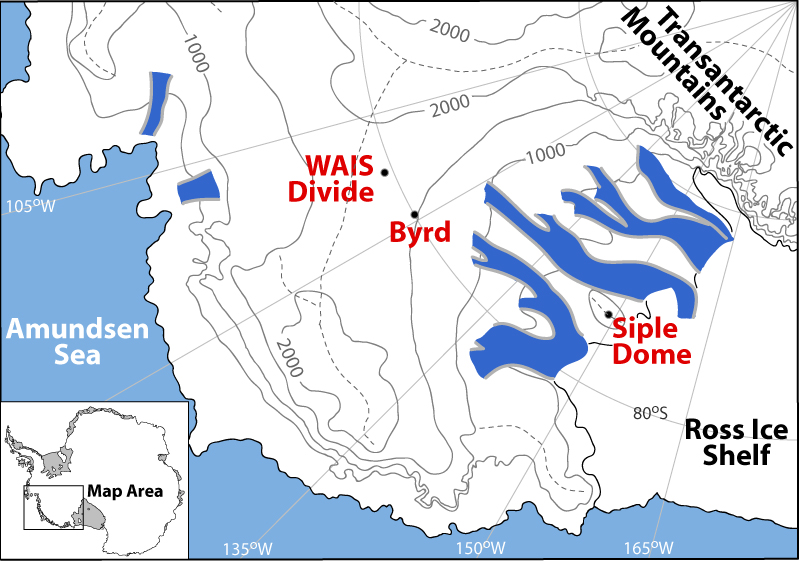

Core Truths Previous Sun story: Deep into WAIS Divide Bangor Daily News: Melting ice at core of climate study WAIS Divide video: Climate Change - How do we know? The constant whine of saws in the room echoes loudly, like some busy school woodshop class. But there’s no smell of woodchips in the air. In fact, it’s hard to smell anything with a runny nose that begins almost immediately upon stepping into the freezing cold lab where scientists are slicing and dicing ice. And not just any ice. This is ice from Antarctica, extracted from the middle of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) by the world’s most advanced ice-coring drill. Researchers from across the United States will eventually analyze various properties of the ice to reconstruct the last 100,000 years of climatic and atmospheric conditions. The results will lead to one of the most detailed histories of the last glacial period, when ice sheets once blanketed parts of North America. The information about the past will also help scientists better understand the links between climate change and greenhouse gases, as the world continues to warm in the 21st century. But first those hundreds of meters of ice cores — which have traveled thousands of kilometers from Antarctica by ship, plane and truck — must be processed. That’s where the National Ice Core Laboratory (NICL) Getting in lineResearchers from around the country, including young scientists working on their doctorates, spent part of their summer at NICL helping to measure, catalog, cut and ship pieces of the ice core to their respective universities and laboratories. The operation is called the core processing line, or CPL. “This is the most challenging CPL we’ve had at the National Ice Core Lab in terms of the amount of ice, the number of projects that are involved in it, the complexity of the sampling, and the coordination of all the groups,” said Kendrick Taylor “We’ve got a really good group of people. Everyone is in super good spirits, which is amazing considering the working environment,” added Taylor, a thickly bearded research professor at the Desert Research Institute in Nevada. The CPL team has less than three months to work its way through 1,400 meters of ice. Most people will spend up to eight hours a day in the CPL lab, which stays at a constant minus 23 degrees Celsius, with plenty of breaks to warm up. It’s even colder in NICL’s main storage warehouse, at minus 34 centigrade, where some 17,000 meters of ice cores from around the world are stored. “It’s kind of brutal with the temperature changes,” said T.J. Fudge Fudge will help run a machine that measures the electrical conductivity of the ice by running electrodes along the length of an ice core section that’s been split and planed smooth.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Sean Michael, an undergraduate from the University of Washington, operates a planer to shave the ice core smooth for electrical conductivity measurements.

Electrical conductivity varies seasonally, offering a way to define and date the layers of the ice core in conjunction with other methods, such as visual stratigraphy, which involves putting a trained eye on each one-meter-long core section. That job falls to Matt Spencer, an assistant professor in the department of geology and physics at Lake Superior State University It’s a rare skill, one that Spencer has volunteered to the CPL team for the summer. He spends his time in a small enclosure shrouded by a black curtain. The core slides along a conveyer belt of rollers into the darkroom, illuminated only by a light table. Spencer bobs his head and shifts his body to peer at the chunk of ice from every possible angle. “It’s really the luck of the draw what you find here in terms of good annual [layers] and bad annual [layers],” he explained. For instance, at a depth of about 1,362 meters, each layer is roughly 15 centimeters wide. But one section seems about double that breadth. There’s probably a divide in there somewhere — but where? “Where the divide is between those two years is sometimes arbitrary,” he said. Other analyses will help sort out the ambiguity.1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |