Winter of discontentUSAP researchers frustrated by backlash against climate sciencePosted October 22, 2010

It hasn’t been a good year for climate scientists. It started in November 2009 with the illegal release of thousands of e-mails and other documents from the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit Subsequent investigations cleared all of the scientists — and reiterated that the research was sound — but the damage had been done in the public arena. The controversy, dubbed “Climategate,” threw a shadow over the next month’s U. N. Climate Change Conference Even the weather got into the act. The winter of 2010 was unusually severe, offering further proof to climate-change skeptics that global warming wasn’t real. For researchers involved in the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP)

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Adélie penguin colonies along the northern Antarctic Peninsula are shrinking due to global warming.

“It’s very frustrating. We don’t know quite what to do with it,” said Richard Alley Forget, for a moment, all you’ve heard about sunspots, ice cores, and the various correlations between carbon dioxide (the primary greenhouse gas) and temperature. Global warming is a matter of physics — one known to science for more than a century, Alley said. [See related article: It's just physics.] “The fact that important people in Washington don’t know that is our failure,” he said. “This is not policy prescriptive, saying there is a greenhouse effect and we’re increasing it. It’s in no way a political statement. Saying there is not a greenhouse effect is a political statement because there’s no scientific basis for it.” Penn State was one of the institutions caught up in the Climategate controversy, as among the stolen e-mails were those by Michael Mann Alley noted that the Associated Press published an article about a month after the e-mail maelstrom erupted, saying that Climategate didn’t show an attempt to fake global warming. “Any time in the past, up until the last few years, I believe that would have ended the story,” Alley said. But it hasn’t. One state attorney general is still attempting to pursue the stolen e-mail case against the University of Virginia, while some candidates for public office have indicated they will launch investigations into climate science if elected. It’s enough to make physical oceanographer Douglas Martinson “It just drives me crazy,” said an exasperated Martinson, a researcher with Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University

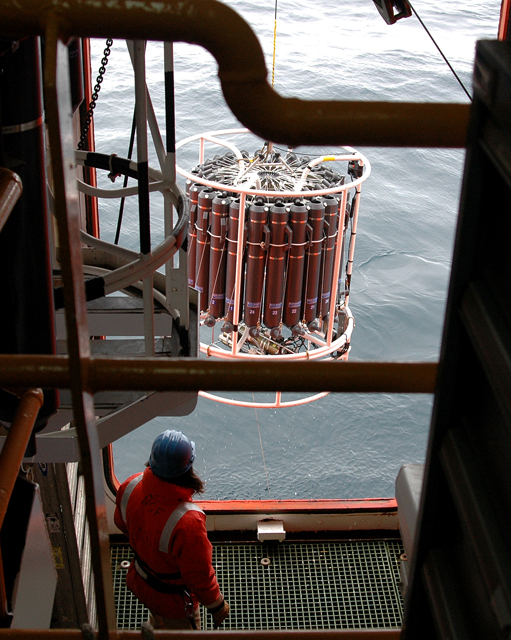

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Palmer LTER scientists use a variety of instruments to measure the current state of the Southern Ocean ecosystem.

“It is so frustrating. We have known for decades — no question — that global warming was started by anthropogenic increases of CO2,” Martinson said, adding that the evidence is overwhelming. “The straws that broke the camel’s back are so thick now you can’t even see the camel.” Collecting the data and making the observations needed to understand climate change in the polar regions isn’t always easy. Don Voigt It’s vital information if researchers are to understand how the world’s great ice sheets will respond to climate change. The Penn State geologist finds himself speaking less about his work these days given the current climate. “We’re just making observations here and trying to tell people what’s going on. Being attacked for an observation is kind of strange — it’s beyond comprehension in a lot of ways,” Voigt said. “At some point you keep doing what you’re doing because you know it’s the right thing to do.” Like Voigt, Leigh Stearns More recently, the assistant professor at University of Kansas’ Department of Geology “It’s such a pervasive change, in the Arctic in particular, and parts of the Antarctic. We need to be better activists of our science. We need to get the word out in a more succinct matter,” Stearns said. “It’s not political. It’s our environment,” she added. An expert in paleoclimatology, Alley has done more than many in his field to make the issue transparent to policymakers and the public. Ten years ago he wrote a popular science book, “The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future,” about the effort and research that went into an ice core extracted from the Greenland Ice Sheet, and its relevance to the climate changes under way today. He’s currently funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF)

Photo Credit: Galen Dossin/Antarctic Photo Library

Icebergs from Pine Island Glacier Ice Shelf in the Amundsen Sea.

Alley admits to some frustration with the media, which traditionally gives two sides to an argument equal weight. Yet the two sides hardly seem equal. A poll performed by Peter Doran More recently, in a 2010 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the authors reviewed publication and citation data for 1,372 climate researchers. They found that nearly 98 percent of the climate researchers most actively publishing in the field support the tenets of anthropogenic-caused climate change. Part of the problem, Alley noted, is that scientific expertise in the media is lacking. “A lot of the mainstream media have gotten rid of their science writers,” he said. In December 2008, for example, CNN cut its entire science, technology and environment team. Today, any talking head on TV can espouse a scientific belief with little or no training, Martinson noted. “People’s opinions being dictated by talk show hosts — it’s just not right,” he said. “Get your information from a scientist, not a talk show host.” |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |