It's just physicsClimate-change expert discusses greenhouse effect, utility of ice-core researchPosted October 22. 2010

“It’s just physics.” That’s the mantra coming from Richard Alley The meeting has brought together most of the polar scientists with interests in the West Antarctic, home to a marine-based ice sheet that has become a cause of concern as the world warms up. Complete disintegration could raise sea level up to 6 meters. On the timescale of the next century, it’s likely to be a major contributor in the one-meter-plus global rise many are predicting. It’s the appropriate setting to discuss global warming with Alley, the Evan Pugh Professor of Geosciences at Penn State, where he has built a reputation as one of the world’s leading experts in paleoclimatology and climate change.

Photo Credit: NASA

Richard Alley

Like many of his colleagues, Alley is frustrated by the recent public backlash against climate scientists. At best, climate skeptics believe global warming is separate from human actions. At worst, they have spun global warming into a global conspiracy. [See related story: Winter of discontent.] “Greenhouse warming is physics,” Alley explained. It’s the familiar but apparently forgotten story of the greenhouse effect, in which radiant energy from the sun warms the surface of the planet, and the longer-wavelength energy sent back by the Earth is partly absorbed by greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor. This traps some of the heat and warms the planet further. “You can see the changes over time from the satellite observations that show how the greenhouse gases are blocking more of it,” Alley said. Think of Earth’s atmosphere as a blanket. Much like you throw another blanket on the bed if you’re cold, pumping more CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere adds more and more layers of blankets, which trap more energy, cranking up the heat. “If you were to say there’s no greenhouse warming from CO2, that it doesn’t matter, you would be violating physics, you would be violating the facts that the satellites see,” Alley said. “If CO2 did not warm, Earth would be largely or completely frozen — a snowball.

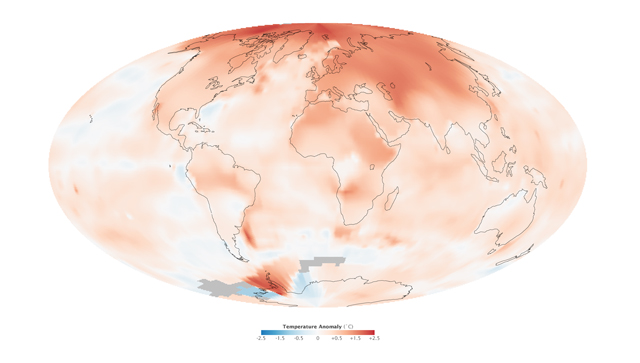

Photo Credit: NASA

A world map shows the how much warmer temperatures were in the decade of 2000-2009 compared to average temperatures recorded between 1951 and 1980.

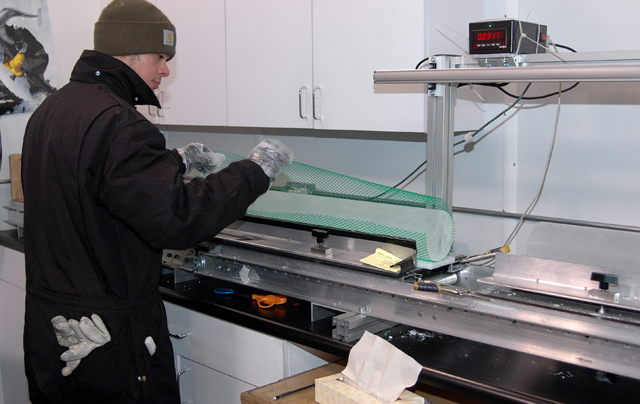

“You would also be unable to explain the history of the Earth’s climate.” Alley is an astute student of that history, but his favorite books are ice cores recovered from the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland. Scientists use ice cores to reconstruct past climate based on various physical and chemical properties of the ice, the atmospheric gases trapped in bubbles, and even the dust that landed on the ice sheet thousands of years ago and was eventually buried by snow and ice. Ice cores are among the best recorders of past climate, and in many cases give the best available information, Alley noted. “By collecting cores from different regions with different snowfall rates, short records with high time resolution and long records with lower time resolution — to more than 800,000 years — are available.” U.S. Antarctic Program His team is interested in the physical properties of the core, literally counting layers and serving as a sort of quality control to ensure abnormalities in the ice aren’t misinterpreted as major flip-flops, or abrupt changes, in climate. They can also estimate temperature on the upper section of the core based on physical processes — simply how snow turns into ice. “One of the beauties of an ice core is that we get to the point of sort of pounding on the table and saying we know what the temperature was, and we know what it was because we’ve done it in so many different ways. Some of those ways are based on physics and not correlations,” Alley said. Other paleoclimate records, such as pollen from a plant recovered in a sediment core from a lake, are correlations that offer good records but are sometimes more difficult to interpret. For example, the changes in pollen composition would record changes in temperature, assuming that the same plants today grow under similar conditions as in the past. But other environmental conditions — rain, sunshine and even competition from other flora — could make the correlation less reliable. “All we’re really assuming is that physics applied in the past. How snow turns to ice is just physics,” Alley explained. “We’re assuming less, and it’s more reliable.” Ultimately, the study of ice cores and other climate recorders is about learning about the past so we can understand in what ways global warming will change the Earth in the future. “Once we’ve actually learned the Earth’s history we have more insight into answers to questions that many people care about,” Alley said. NSF-funded research in this article: Richard Alley, Pennsylvania State University, Award No. 0539578 |