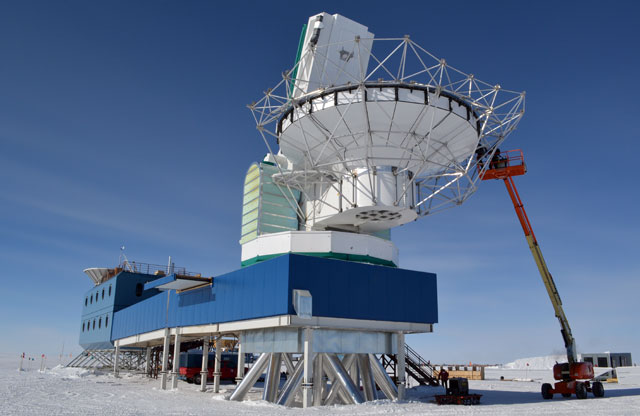

Mission completeSouth Pole Telescope finishes five-year survey of galaxy clustersPosted March 16, 2012

Its five-year mission: To survey the early universe for massive galaxy clusters, a search designed to understand more about one of cosmology’s greatest mysteries — dark energy Mission complete. Now it’s time for something new. The South Pole Telescope (SPT) “We’re trying to understand what dark energy could be, and our way of looking at it is to see the structures involved,” explained John Carlstrom Galaxy clusters, thanks to the pull of gravity, are the largest structures to have evolved in the cosmos. The SPT hunts for them using the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SZ) effect In 2008, the telescope detected its first galaxy clusters using the SZ effect. Two years later, astronomers announced the discovery of the most massive galaxy cluster yet, tipping the scales at the equivalent of 800 trillion suns, and holding hundreds of galaxies. [See previous article — Heavyweight discovery: South Pole Telescope finds most massive galaxy cluster to date.] Mapping the number of such clusters over the history of the universe can tell researchers how much influence dark energy had on their growth, according to Bradford Benson

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

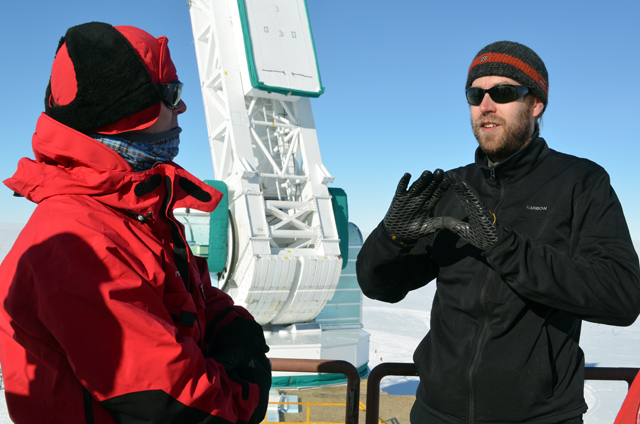

Bradford Benson, right, explains the South Pole Telescope experiment to Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg.

It sounds like a disembodied entity that Captain Kirk and company might battle in an episode of Star Trek. Dark energy is the prevalent explanation for the accelerating expansion of the universe. Dark energy appears to counteract the gravitational attraction between galaxies. In a younger, smaller universe billions of years ago, gravity had a greater influence, allowing galaxy clusters to grow and clump together like dust bunnies on a wood floor. In a study last year using SPT data, lead author Christian L Reichardt “Everything is getting diluted. Dark energy is just sitting there,” said Carlstrom, director of the Kavli Institute of Cosmological Physics Now, Carlstrom, Benson and their team want to peer back to near the beginning of time, a fraction of a moment after the Big Bang, when the universe expanded exponentially, a theory known as inflation.1 2 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |