Shrinking backLarsen B Ice Shelf appears ready for final collapsePosted April 20, 2012

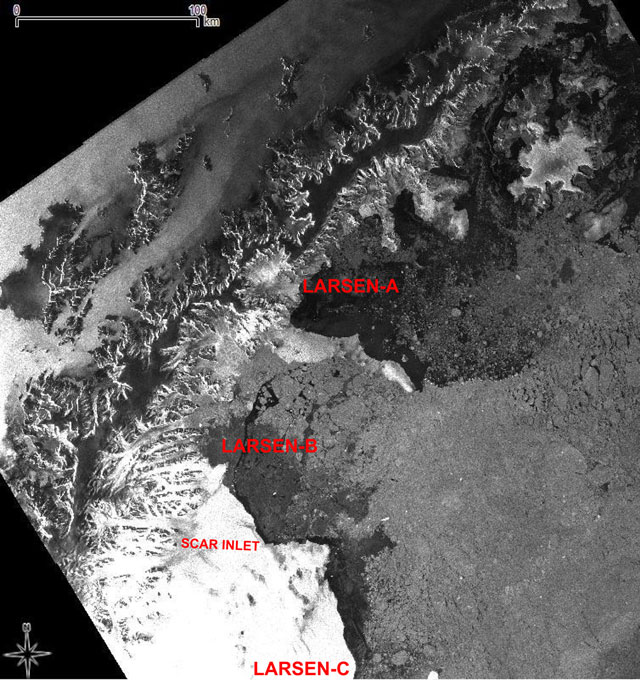

A European Space Agency (ESA) The Larsen B Ice Shelf Now, only about 1,670 square kilometers remain, and it may be only a matter of time before the ice shelf completely disappears. “What may be about to happen in the Larsen B is a different kind of break-up, one where the ice shelf tears itself apart due to an inability to resist the relentless shove of ice behind it,” explained Ted Scambos Scambos explained in an email that the loss of the main ice shelf area 10 years ago completely changed the stress pattern within the remaining section of Larsen B. In turn, that affected the glaciers that fed ice into the diminished ice shelf. “As several studies have shown, these glaciers accelerated almost immediately, and reached speeds several times faster than their pre-breakup flow rates,” he said. “For the remnant shelf area, the loss of resistive stress provided by the ice that disintegrated led to a series of major [iceberg] calvings in 2003, 2006 and 2009.” Scambos added that the 2002 break-up led to an increase in rifting deep within the ice shelf. “Major changes have already occurred along the shear areas and rift of the shelf, and these were initiated by the 2002 break-up,” he said. The Larsen Ice Shelf was the name applied by explorers to a nearly continuous ice shelf area in the northwestern Weddell Sea, with three distinct embayments. As these began to change in different ways due to 20th century warming, glaciologists gave the three embayment areas different names. The Larsen A, the northernmost, broke apart in 1995. The Larsen B disintegrated in 2002, and it continues to change rapidly. Farther south, the Larsen C has to date shown much more subtle changes. The Larsen C is the largest by far, bogger than the states of New Hampshire and Vermont combined. Satellite observations have shown some thinning and an increasing duration of summer melt events there, according to ESA. However, Scambos said that climate warming in the region has slowed from the “brisk pace” that occurred in the 1990s through 2006. He said the past five years have seen slightly cooler conditions. “The peak in warming appears to be 1995,” he said. “There have been few melt ponds since the 2006 season, except for a brief period in November of 2010.”

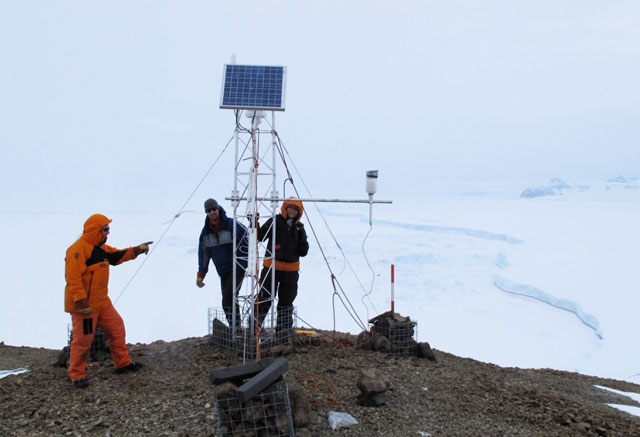

Photo Credit: Amber Lancaster/PolarTREC

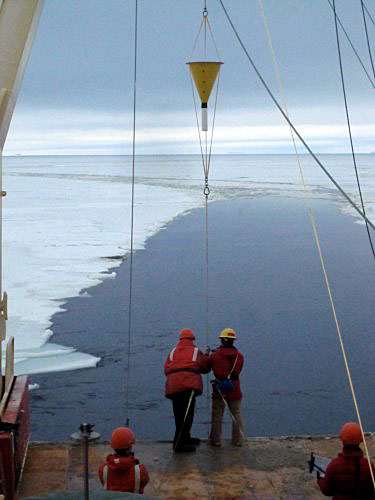

Personnel aboard the research vessel NATHANIEL B. PALMER prepare a sediement trap for deployment during the LARISSA cruise.

Those data are based on automatic weather stations, as well as field research and instrument installations near the ice shelf by Scambos and colleagues in recent years as part of a large interdisciplinary project called LARISSA, for LARsen Ice Shelf System, Antarctica A product of the International Polar Year The researchers are pooling their expertise to understand the conditions that led up to disintegration of the Larsen B, looking not only at the more immediate evidence, but traveling back thousands of years in the region’s climate history using sediment and ice cores. Other team members are studying the effects of the ice shelf collapse on the local biology and oceanography. A second ship-based expedition is currently in the Weddell Sea, following up on a research cruise to the region in early 2010 that met stiff resistance from sea ice, which prevented the research vessel Nathaniel B. Palmer However, a ski-equipped Twin Otter operated by the British Antarctic Survey The LARISSA observatories are providing the researchers with local weather data, ice flow speed, and images of events such as iceberg calvings and snowfall, according to Scambos. Meanwhile, the current expedition aboard the Palmer is collecting sediment cores, biological specimens, ocean profiles of temperature and salinity and other samples in the peninsula region. “The current LARISSA cruise is conducting great work just north of the Larsen B, in the earlier-disintegrating Larsen A basin,” Scambos reported. “Sea ice is making access to the Larsen B basin challenging, but the team is hoping to sneak in if a good storm pushes the ice out of the embayment.” In a recent ship report filed by chief scientist Maria Vernet “All science groups are finding intriguing results on the oceanography, ecology and geology that will help explain the interactions that characterize pre- and post-ice shelf break up earth science processes in the eastern Antarctic Peninsula,” she added. Scambos said it appeared that even a decade after the dramatic break-up of the Larsen B Ice Shelf, the area is still evolving and adjusting. “The pace of climate warming has slowed, but the next steps may still lead to ice loss and glacier speed-up, echoing the astounding warmth of the early 2000s in the area.” NSF-funded research for LARISSA: Eugene Domack, Hamilton College, Award No. 0732467 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |