|

Historical contextMcMurdo LTER adds social sciences to research programPosted May 18, 2012

[Editor's Note: One in an ongoing series about the McMurdo Dry Valleys Long Term Ecological Research program, which is entering its 20th season in Antarctica.] The McMurdo Dry Valleys Colorado State University He is one of the newest members of the McMurdo Dry Valleys (McM DV) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) program “All of the LTER sites around the United States are trying to include some sort of social science to their research. In some ways, it’s harder to do in Antarctica, but it fits neatly with environmental history,” Howkins said a few months after returning from his second trip to the Ice. The LTER Network The peninsula region was actually the focus of Howkins’ doctoral dissertation at the University of Texas at Austin “It turned out to be a very interesting place for looking at the use of science in the dispute and the environment in contesting sovereignty,” said Howkins, who is adapting the dissertation into a book that he hopes to publish in the next couple of years. Environmental history emphasizes the role nature plays in influencing human events and vice versa. For example, in the conflict between Chile and Argentina, the natural border created by the Andes between the two countries was seen as a way to make territorial claims along the Antarctic Peninsula, where the spine of South America’s longest mountain range eventually reemerges. “It proved to be a great spot for thinking about questions of environmental history,” Howkins noted. Human history in the McMurdo Dry Valleys goes back a little more than a century, to 1903, when members of Robert Falcon Scott and his party with the Discovery expedition discovered them. Less than a decade later, when Scott returned to Antarctica in a bid to become the first to reach the South Pole, members of his research team made the first concerted scientific studies of the area. That team was led by Thomas Griffith Taylor, a prominent geographer and anthropologist of the time, and for whom the Taylor Valley is named. It was Taylor’s journal that guided Howkins during the latter’s own exploration of the Dry Valleys during the 2011-12 field season with the LTER group. Strangely, Howkins noted, Taylor’s published map of his namesake valley left off a prominent feature, Lake Fryxell, which led him to wonder if the ice-covered body of water had been much smaller a century ago. It turned out to be human error. “That’s an example of trying to use the history to think about what has changed [in the environment],” Howkins said.

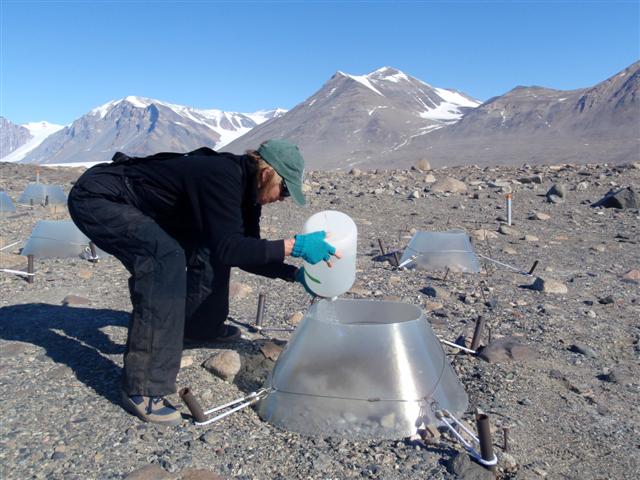

Photo Credit: Byron J. Adams/Antarctic Photo Library

CSU scientist Diana Wall conducts a soil experiment in the McMurdo Dry Valleys.

Taylor’s notes also describe in detail the meltwater streams and moats that form in summer, suggesting that they were much smaller than today. There is growing evidence that implies climate change in the Dry Valleys is driving sudden flooding events in the summer, turning transient streams into rivers and swelling the lakes. [See previous article — Flooded out: Rising lake levels in the McMurdo Dry Valleys affect science, field camps.] “That sort of historical data, while not scientific in a sense, helps to think about what has changed in the valleys,” Howkins said. Diana Wall “I think the benefits of environmental history from the Dry Valleys are that we cannot only understand the excitement of exploration and discovery, but more importantly, use the information to inform us in our research today,” Wall said. “That is key for studying and understanding the environmental problems that impact these ecosystems.” Howkins’ research will also take him to England this summer to examine the papers of another prominent scientist from the expedition, Frank Debenham, who went on to become the first director of the Scott Polar Research Institute “That will give me another perspective on the same questions,” Howkins said. “We’ve learned that we can’t trust everything that Taylor was saying. He was making mistakes.” Eventually, Howkins hopes to write a comprehensive environmental history of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, conducting as many oral history interviews as possible with the scientists who have worked in the region, dating back to the International Geophysical Year (IGY) “If anyone has been there, and would be interested in talking to me, I’d love to talk to them, especially from the older period,” Howkins said. The book will naturally focus on the last 20 years of the LTER program, which has grown to include about a dozen principal investigators and several generations of students. “That’s one of the fascinating things,” Howkins noted, “you’ve got such a short human history. The LTER now is one-fifth of the human history of the Dry Valleys.” NSF-funded research in this story: Adrian Howkins, Colorado State University, Award No. 1115245 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |