|

No small discoveryMicrobial life found in extreme environment of Antarctica's Lake VidaPosted December 7, 2012

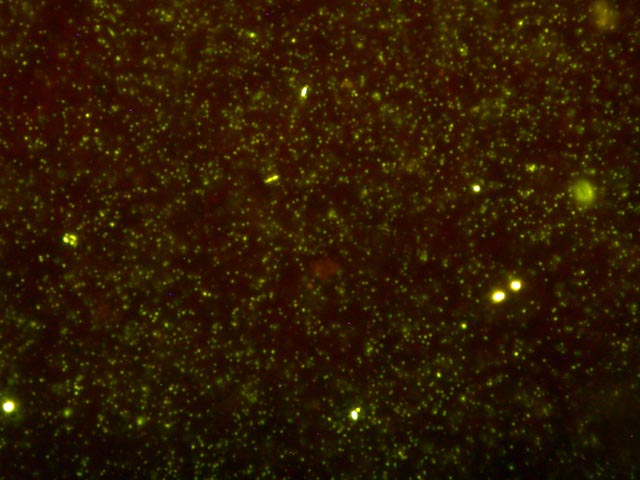

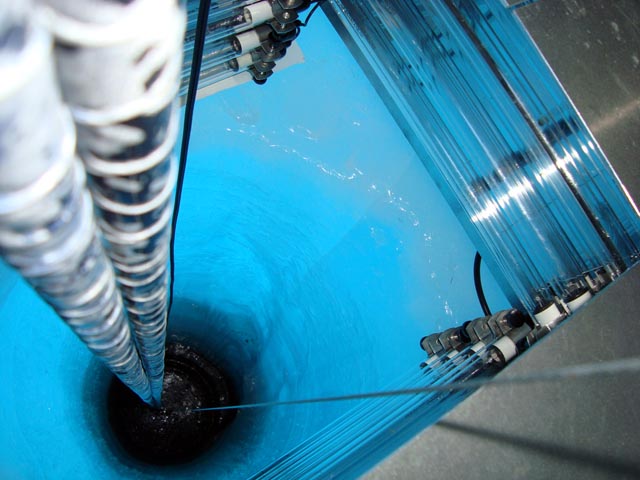

Talk about a tough place to live, even by Antarctic standards. First, there is no oxygen in Lake Vida, one of several unique lakes found in the McMurdo Dry Valleys But somehow a community of bacteria ekes out a living in this dark, salty and subfreezing environment, expanding our understanding of how life persists in extreme environments on Earth and possibly other worlds, according to a new study led by researchers from the Desert Research Institute (DRI) “This study provides a window into one of the most unique ecosystems on Earth,” said Alison Murray “Our knowledge of geochemical and microbial processes in lightless icy environments, especially at subzero temperatures, is mostly unknown up until now,” added Murray, a polar researcher for the past 17 years, who has participated in 14 expeditions to the Southern Ocean and Antarctic continent. “This work expands our understanding of the types of life that can survive in isolated, cryoecosystems and how different strategies can be used to exist in such challenging environments.” Despite the very cold, dark and isolated nature of the habitat, the authors report that the brine harbors a surprisingly diverse assemblage of bacteria that survive without a present-day source of energy from the sun. Previous studies of Lake Vida dating back to 1996 indicate that the brine and biota have been isolated from outside influences for more than 3,000 years. In 2005 and 2010, researchers sampled deep into the subsurface ice of Lake Vida to collect brine existing in a voluminous network of channels 16 meters and more below the lake surface. Murray and her co-authors and collaborators, including Christian Fritsen The team set up a field camp on Lake Vida, located in Victoria Valley, the northern most of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, where they worked for six weeks during the two field seasons to collect samples. The researchers worked under a tent on the lake’s surface to keep the site and equipment clean as they drilled a hole through the frozen water. Everything that went down the hole was sterilized like a surgical tool. An ultraviolet light system under the floor of the tent gave the instruments a final dose of UV radiation for good measure. The scientists collected ice cores that contained samples of the salty brine and lake sediments, which can offer insight into the history of Lake Vida itself. They then assessed the chemical qualities of the water and its potential for harboring and sustaining life, in addition to describing the diversity of the organisms detected. The brine these microbes call home is anoxic, or oxygen-free, slightly acidic, and contains very high levels of organic carbon and molecular hydrogen, as well as both oxidized and reduced nitrogenous compounds. Geochemical analyses suggest that chemical reactions between the brine and the underlying iron-rich sediments generate nitrous oxide and molecular hydrogen. The latter, in part, may provide the energy needed to support the brine’s diverse microbial life. “It’s plausible that a life-supporting energy source exists solely from the chemical reaction between anoxic salt water and the rock,” Fritsen said. “If that’s the case, it will change our view entirely regarding how we look for the existence of cryogenic and potentially, life-supporting ecosystems.” Murray added further research is currently under way to analyze the abiotic, chemical interactions between the Lake Vida brine and the sediment, in addition to investigating the microbial community from parallel genome sequencing approaches. “Results could help explain the potential for life in other salty, cryogenic environments beyond Earth,” Murray said. “The Lake Vida brine also represents a cryoecosystem that is a suitable and accessible analog for the soils, sediments, wetlands, and lakes underlying the Antarctic ice sheet that other polar researchers are just now beginning to explore.” NSF-funded research in this story: Peter Doran and Fabien Kenig, University of Illinois at Chicago, Award No. 0739698 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |