|

Cold enough for you?Scientists study how Weddell seals regulate heat in the AntarcticPosted February 1, 2013

Biologist Allyson Hindle hoists the VHF antenna high in the air, listening intently to the radio receiver for the telltale signal that her Weddell seal pup is somewhere close. A thick blanket of clouds sits low across the sea ice that covers McMurdo Sound. The light is flat. The snowmobile ride out from McMurdo Station Summer is in full bloom in Antarctica, and that means melting ice, slush and small pools of water forming in the ephemeral ice cover. Hindle and the rest of the research team only have a few days left to locate a half-dozen seals that still carry the valuable instruments the team glued on them about a week ago.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Biologist Allyson Hindle attempts to locate a tagged Weddell seal with a VHF receiver.

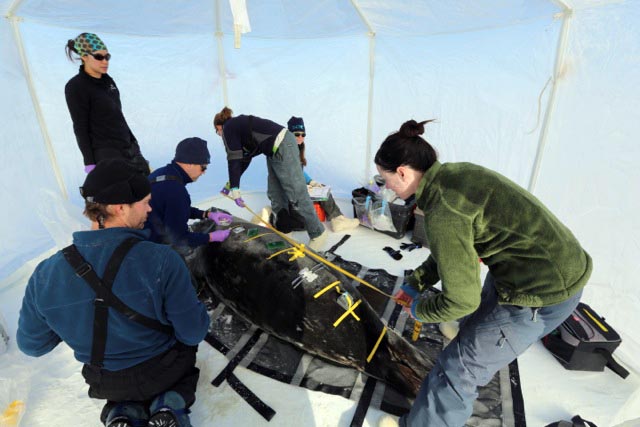

The game of hide-and-seek with the Weddell seals has Jo-Ann Mellish “You just sort of assume that if an animal lives in a certain habitat that they’re adapted to it — but nobody has actually looked,” said Mellish, a research associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks “We need a baseline to understand how they may respond to environmental change, which is clearly going on at both poles,” she added. Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) are endemic to the Antarctic, and are named after the British sealing captain James Weddell. The animals are among the super athletes of the Southern Ocean, capable of diving 750 meters or deeper into the frigid polar waters. Forays under water can last more than an hour. On the surface, however, Weddell seals appear far less graceful, worming their blubber-cast bodies ever so slowly to and from their dive holes in the sea ice. The animals have set up home not far from McMurdo Station. Other researchers have studied the Erebus Bay colony now for more than 40 years, offering a rich dataset on each animal’s life history for Mellish’s team. “For us, it’s the perfect outdoor lab where we can learn a lot about one species at a go,” explained Mellish, whose work on studying the physiology and ecology of Arctic marine mammals is far more logistically challenging. And while chasing fast-swimming seals around the open ocean may sound like grand adventure, the accessibility of the Weddell seals is preferable for the kind of experiments designed by Mellish, Hindle and the project’s other co-principal investigator, Markus Horning Horning is what Mellish calls “the gear head” of the scientific triumvirate. He is involved in helping develop the instruments the team uses to capture physiological measurements in data loggers attached to the animals. “We work with manufacturers with the purpose of developing very specific devices that collect very specific types of data,” Horning said. “It’s not trivial to collect this kind of data. We’re talking about animals that are absent from our ability to directly observe them for most of their lives.”

Photo Credit: Henry Kaiser

Scientist Markus Horning holds the heat flux sensor package and data logger.

To answer the question of whether seals get cold — or, in more formal science speak, quantifying the energetic requirements to thermoregulate in and out of the water — Horning came up with special heat flux sensors with Wildlife Computers The sensors are small discs glued to the seal’s fur with an epoxy. They measure the amount of heat transferred across the animal’s body to the air. Cables from the heat flux sensors plug into the data loggers, cell-phone sized instruments that also collect physical ocean properties like salinity and temperatures, as well as dive behavior such as depth and acceleration. “We’re able to collect a lot of data about these animals and their thermoregulatory physiology that simply hasn’t been done or hasn’t been able to be done in the past,” noted Hindle, with the University of Colorado in Denver Her biggest task will come after this second field season is over: building a computer model from the field data and physiological assessments done for each animal to determine how much energy it expends in the course of a day. “The cost of being a seal in air is different than the cost of being a seal in water,” Mellish noted. The animals swim in water that hovers just below the freezing point year-round, kept liquid thanks to the high salt content. Of course, water conducts heat away from the body 25 times faster than the air. Summer temperatures can be several degrees above freezing, but wind chill can send the temperature into double digits below zero. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |