|

Making wavesTwo new studies link ozone hole with changes in oceanic, atmospheric patternsPosted February 8, 2013

A pair of studies published this month in the prestigious journal Science link ozone depletion over the Antarctic to powerful changes in atmospheric and ocean circulation. Such changes may have global implications, from altering precipitation patterns to weakening the sequestration of carbon dioxide in the ocean. One paper, co-authored by Sukyoung Lee and Steven Feldstein “Previous research suggests that this southward shift in the jet stream has contributed to changes in ocean circulation patterns and precipitation patterns in the Southern Hemisphere, both of which can have important impacts on people’s livelihoods,” Lee said in a Penn State press release

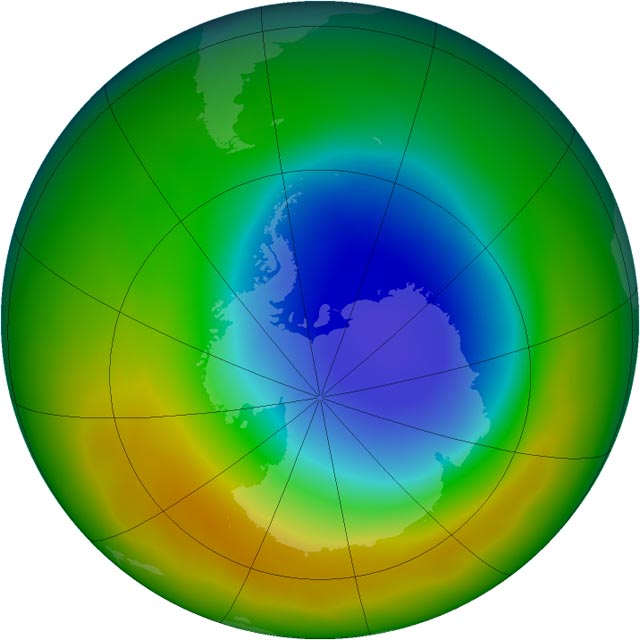

Photo Credit: NASA

False-color view of total ozone over the Antarctic. The purple and blue colors are where there is the least ozone, and the yellows and reds are where there is more ozone.

Based on modeling studies, both ozone depletion and greenhouse gas increases are thought to have contributed to the southward shift of the Southern Hemisphere jet stream, with the former having a greater impact, according to Lee. However, until now, no one has been able to determine the extent to which each of these two factors has contributed to the shift using observational data. “Understanding the differences between these two forcings is important in predicting what will happen as the ozone hole recovers,” Lee said. “The jet stream is expected to shift back toward the north as ozone is replenished, yet the greenhouse-gas effect could negate this.” Lee and Feldstein developed a new method to distinguish between the effects of the two forcings. The method uses a cluster analysis to investigate the effects of ozone and greenhouse gas on several different observed wind patterns. “Not only are the results of this paper important for better understanding climate change, but this paper is also important because it uses a new approach to try to better understand climate change; it uses observational data on a short time scale to try to look at cause and effect, which is something that is rarely done in climate research,” Feldstein said. “Also, our results are consistent with climate models, so this paper provides support that climate models are performing well at simulating the atmospheric response to ozone and greenhouse gases,” he added. Meanwhile, a paper by Waugh, et. al. in the same issue of Science suggests that the hole in the ozone layer has caused changes in the way that waters in the Southern Ocean mix. Previous research has linked the strengthening of westerly winds around the continent with stratospheric ozone depletion. In turn, those winds have drawn circumpolar deep water to the surface. Darryn W. Waugh CFC-12 was produced commercially in the 1930s and its concentration in the atmosphere increased rapidly until the 1990s when it was discovered as the primary culprit for ozone depletion. (A treaty known as the Montreal Protocol From those ocean measurements, Waugh’s team was able to infer changes in how rapidly surface waters have mixed into the depths of the seas. Because they knew that concentrations of CFCs at the ocean surface increased in tandem with those in the atmosphere, they were able to surmise that the higher the concentration of CFC-12 deeper in the ocean, the more recently those waters were at the surface. “The water from deep in the ocean may not have seen the surface for hundreds of years,” Waugh told the New York Times. “This ‘old’ water is very carbon-rich, from dead organic matter that sinks to the bottom of the ocean.” When water that is already high in carbon dioxide is pulled to the surface, the ocean in this area absorbs less carbon, according to Waugh. “This matters because the [Southern Ocean plays] an important role in the uptake of heat and carbon dioxide, so any changes in Southern Ocean circulation have the potential to change the global climate,” Waugh said in a press release The key thing abou the Lee and Feldstein paper is that it's been the ozone hole that has led to a southward shift of the westerly jet stream, according to Peter Milne, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences "If the ozone hole subsequently recovers, this steepening of the gradient may lessen," Milne noted. NSF-funded research in this article: Steven Feldstein and Sukyoung Lee, Penn State, Award No. 1036858

|

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |