|

UnhingedNew paper challenges gateway hypothesis for Antarctic glaciationPosted Aug 23, 2013

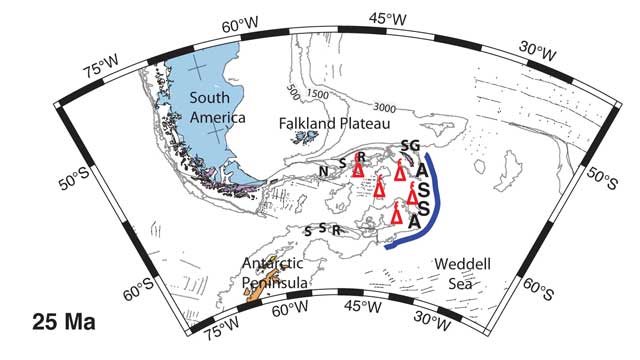

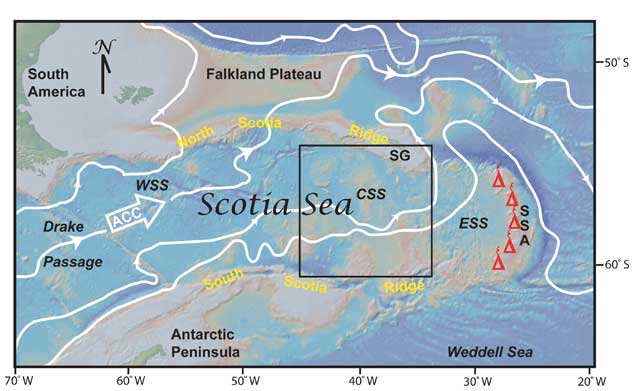

One of the enduring theories of how Antarctica initially entered a deep freeze about 34 million years ago has taken some knocks over the years — but a recent paper in the journal Geology may eventually blow the doors off the so-called gateway hypothesis. It was at about that time of initial glaciation that some researchers believe the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) that encircles the continent formed. The event would have coincided with the opening of ocean passageways between Antarctica and its neighboring continents Australia and South America. The deep ocean current would have isolated Antarctica — its massive ice sheets began to grow at around that time — and helped tip the world into a cooler period. But rocks dredged from an area of the Southern Ocean known as the central Scotia Sea suggest a volcanic arc existed as late as 12 million years ago east of the Drake Passage, one of the key gateways between Antarctica and South America. The underwater topography from such a rise in the seafloor would have impeded the formation of a deep ocean current, implying that the ACC didn’t initiate Antarctic glaciation. “We didn’t go out trying to find this,” explained Ian Dalziel Dalziel led a research cruise aboard the U.S. Antarctic Program’s The rock types and geochemical data suggest that the equivalent of today’s South Sandwich volcanic island arc existed between the South Georgia and South Orkney islands, according to Dalziel, a research professor at UT Austin’s Institute for Geophysics “Today, the South Sandwich arc forms a very significant barrier to the Antarctic Circumpolar Current,” he said. “It diverts it north through a couple of significant gaps in the North Scotia Ridge.” Colleagues from the University of Cardiff “[Our paper] really casts doubt on one of several hypotheses of what drove the planet into its present-day glaciation, which started 34 million years ago during the Eocene-Oligocene boundary,” he said. Some researchers believe concentrations of carbon dioxide declined, reaching a tipping point of about 760 parts per million in the atmosphere, based on evidence from microfossils. The Eocene-Oligocene boundary is marked by a large-scale extinction of both plants and animals, though it’s not considered a major extinction event. The cause of the drop in carbon dioxide (CO2) is unknown, though some have suggested that the rise of both the Tibetan Plateau and South America’s Antiplano at about the same time may have drawn CO2 out of the atmosphere through chemical weathering of the rocks.

Photo Credit: NASA

An aerial photo of South Georgia Island taken from the International Space Station.

David Barbeau Like Dalziel, Barbeau was funded by the National Science Foundation’s Division of Polar Programs Barbeau and his team have worked for the last half-dozen years along the tips of South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. Once upon a time, before the Drake Passage formed, the Andes stretched across both continents. Barbeau believes that by matching and dating rock and sediment samples on both sides of the Drake, he can better determine when the passageway opened. Barbeau noted that work by his team and others offer evidence that the Drake Passage first opened at least 40 million years ago. He said geochemical data from the Southern Ocean collected by Howie Scher and Ellen Martin at the University of Florida “quite convincingly record the incursion of significant volumes of Pacific-derived seawater into the South Atlantic by around 41 million years ago. “It is difficult to envision this happening without a significant and probably vigorous marine conduit through Drake Passage,” Barbeau added. He said his group is in “the final stages of comparing the provenance of sediment deposited in basins on opposite sides of Drake Passage, which we hope will enlighten the region’s separation history.” One unexpected result so far: The composition of the basins deviated much earlier than expected — at least 60 million years ago. “Whether this is a reasonable proxy of [the Drake] Passage opening remains to be seen, and will certainly face scrutiny,” Barbeau said. “Regardless of whether or not the interpreted magmatic arc impeded sufficient circumpolar circulation to thermally isolate Antarctica, Dalziel and colleagues’ contribution is significant in that it convincingly addresses a number of long-standing questions about the tectonic evolution of the Scotia Sea,” he added. Dalziel doesn’t dispute the dating of the Drake Passage. In fact, he also suggested that it might have opened earlier than 34 million years ago based on chemical analyses of shark teeth. However, he argued it and other gateways may have been much shallower than today, when the ACC charges around the continent from west to east at depths of more than 3,000 meters. Instead, Dalziel said it appears the world’s largest ocean current didn’t really get going until about 12 million years ago, which coincides with a marked decrease in ocean temperatures. About seven million years ago, glaciation spread to the Antarctic Peninsula, which juts farther north than the rest of the continent, crossing the Antarctic Circle. “The suggestion is that [the ACC] might have been related to the deeper descent into the icehouse in the late Miocene,” Dalziel said. Dalziel conceded that there are still gaps to fill in the story. He and his team plan to revisit the Scotia Sea in September 2014 to collect more samples. In addition, they’ll install a high-precision GPS unit on South Georgia Island to determine if the current tectonic movement matches theory. “If our story is correct, then South Georgia Arc has collided with a feature northeast of it called the Northeast Georgia Rise,” Dalziel said, adding that it will take four or five years before the GPS can catch a clear signal of the continental drift. It seems like a long time to wait for results, but it’s not even the blink of an eye when you deal in epochs on the scale of millions of years. And the findings never get old. “We went out with the idea there was a problem, and as often happens in science, we found something different than we expected to,” Dalziel said. >NSF-funded research in this story: Ian Dalziel and Lawrence Lawver, University of Texas at Austin, Award No. 0636850 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |