|

Erebus eruptsAntarctica's famous volcano shows signs of life not seen in nearly 30 yearsPosted November 15, 2013

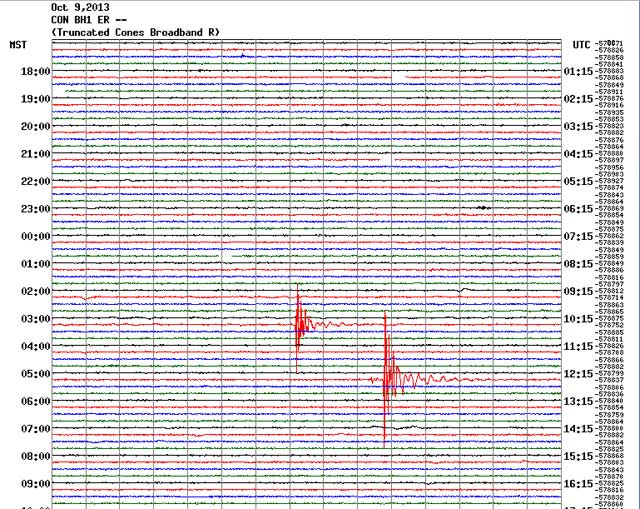

There were hints as early as August. In October, however, the signs that Erebus volcano was waking up in a big way became unmistakable. By Oct. 9, a broadband seismic station “That is not a trivial eruption. That’s a big explosion – that’s a lot of energy,” said Philip Kyle “It’s probably the largest we’ve had since 1984,” Kyle added. The volcanologist has been conducting research on Erebus volcano for more than four decades. Its exceedingly rare lava lake and accessibility from nearby McMurdo Station Now the latest fit from the smoldering volcano has him more eager than ever to return to his field camp at Lower Erebus Hut to monitor the most on-going activity. “It’s doing something. It’s alive,” Kyle said. Fieldwork this austral summer may include collecting specimens from the bombs – hot molten rocks – that are likely being launched out of the crater and onto the sides of the 3,794-meter-high volcano and mapping their distribution. Additional studies will focus on the witches’ brew of gases that spew out of the crater. A top priority is also to recover a thermal infrared camera that sits at the volcano’s rim. A nearby seismic station, which shares the same power source, stopped transmitting data. Kyle fears an Erebus bomb might have hit the expensive instrument or its power source. “We have huge worries that camera was hit,” he said. Each eruption throws up to 50 to 100 bombs. Some fall back into the crater, but others are likely landing on the crater rim. Up to a half-dozen eruptions are occurring almost daily.

Photo Credit: MEVO

A broadband seismic station called Cones detects a major eruption from Erebus on Oct. 9.

“We are getting bombs thrown out nearly every day,” Kyle speculated from the size of the seismic signals. Erebus has slumbered in relative peace since a similar series of eruptions from the latter half of 2005 into 2007. [See previous article — Throwing a fit: Mount Erebus experiences one of its most active seasons in 165 years.] The only other time the volcano has kicked up such a storm in recorded history occurred in 1984, when Erebus launched bombs measuring 10 meters wide and slung them as far as 3 kilometers away from the crater “Erebus is always having little explosions,” Kyle explained last month during an interview in Denver during the annual Geological Society of America meeting Until now. So far, Kyle concedes, the evidence is all from remote monitoring. A couple of broadband seismometers, which measure and record the size and force of underground energy or seismic waves, are still in service along the flanks of the volcano. Data from an infrasound sensor on the nearby ice shelf, used primarily to monitor weapons of mass destruction as part of the international Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) “Those are incredibly valuable,” Kyle said of the data collected by the CTBT infrasound sensor at a place called Windless Bight. “They’ve been there forever. They’ve been off limits until now. … It’s probably the best record.

Photo Credit: Phil Kyle

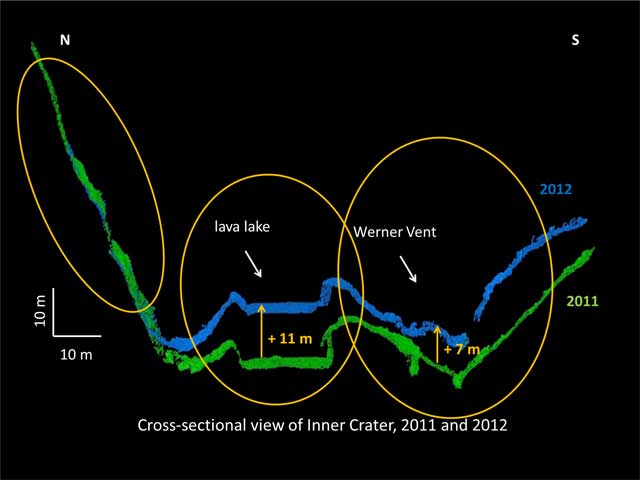

A graphic shows the changes in Erebus' lava lake level inside the crater between 2011 and 2012.

“The infrasound really does confirm that these are big eruptions,” he added. “No one has seen anything. We know nothing, but it is fair to say that these must be throwing lots of bombs.” The remote data, combined with more than 40 years of familiarity with Erebus, has Kyle fairly confident about the intensity of the recent activity, which he believe is closer to what happened back in 1984. “At the time, there were bombs landing everywhere around the Upper Hut,” he said, referring to a field camp only 100 meters from the crater rim that had to be abandoned due to the burst of violent eruption nearly 30 years ago. Kyle still recalls with a flashback of terror stepping out of the helicopter near Upper Hut and seeing a smoking, blackened rock only a meter or two away. He quickly jumped back into the helicopter and told the pilot to take off as fast possible. The reason behind the latest outburst is unclear. Kyle doubts that it is a prelude to a more violent explosion, though big eruptions have certainly occurred in the distant past. Volcanic ash linked to Erebus has been found at least as far as the Transantarctic Mountains hundreds of kilometers away, he said. Instead, he suspects the most recent activity may be related to the volcano’s lava lake, an endless source of study, science and speculation. Kyle has called the fiery pit a window into the magma chamber and the inner workings of the volcano, which has been active for about 1.3 million years. For about a decade, the lava lake appeared to be drying up, based on laser-based measurements of the crater. LIDAR imagery of the volcanic lake dates back as early as 2001 when airborne laser measurements were made. Since 2008, LIDAR has been used at the crater rim to take detailed snapshots of its structure. The lake level had actually dropped three meters per year between 2001 and 2011, becoming what Kyle called a “piddly little lake” before suddenly roaring back to life, springing back up more than 11 meters. “The whole floor came all the way back up,” he said. “This new activity might be related to that. “From our point of view this is really exciting stuff,” he said. NSF-funded research in this story: Philip Kyle and Clive Oppenheimer, New Mexico Tech, Award No. 1142083 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |