Finding NemoOr, in the case of Antarctica, locating penguins by satellite to assess species healthPosted August 8, 2014

High-resolution satellite imagery is refining and reinventing the way scientists track and study wildlife populations, particularly in the Antarctic, where researchers have made headline-grabbing discoveries about Adélie and emperor One study, published in July in The Auk, Orinthological Advances, a leading scientific journal focusing on birds, found that the breeding population of Adélies was more than 50 percent higher than previously estimated. A second study, first presented at the ideacity conference in Toronto In both cases, researchers employed satellite imagery to locate the species’ breeding grounds, through the telltale signature of guano stains, leading to new insights about some of Antarctica’s most studied animals. Among the authors on both studies are Stony Brook University

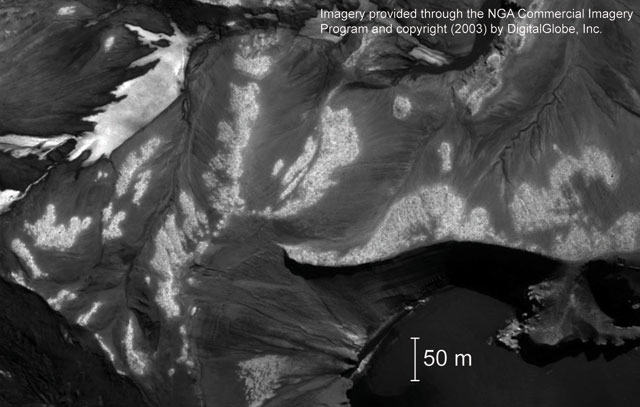

Photo Credit: ©DigitalGlobe Inc.; Image provided by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Commercial Imagery Program

A satellite image shows chinstrap penguin colonies at Baily Head, Deception Island, in 2003. The white patches are the colonies.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

Adélie penguins ride an ice floe in McMurdo Sound.

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek/Antarctic Photo Library

Adélie penguins porpoise through the water of McMurdo Sound.

They say some progress has been made to refine their techniques, though some challenges still remain the same, such as the inability to pierce through cloud cover, which often persists over the Antarctic Peninsula. “We have a lot more experience now with the manual human interpretation,” explained Lynch, part of a team that is involved in a long-term census of penguins around the Antarctic Peninsula called the Antarctic Site Survey “We are getting more imagery coming in all the time, which makes it easier to work around issues like cloud cover, because we have more images and can pick and choose the best,” she added. “We still have some challenges with automated detection with very high-resolution imagery, but it’s an area we are exploring.” LaRue agreed that automation is still not ready to replace more time-consuming manual methods just yet. “We have statistical models for turning [an] area of guano into number of birds, at least for Adélie penguins, but defining the areas themselves still requires a lot of manual interpretation of the imagery,” she noted. The Auk journal paper offered the first-ever global census of Adélie penguins thanks to the bird’s eye view that satellites provide. Researchers estimate a population of 3.79 million breeding pairs, or 53 percent larger than previously thought. An additional 17 populations not known to exist were discovered during the satellite sweep of the Antarctic. LaRue said she wasn’t particularly surprised by the increase in worldwide Adélie numbers, which reflects both a growth in known populations and the addition of previously unknown colonies. “But, to be fair, I was responsible for images on the continent where we found all the new colonies and where populations are increasing, so I was primed for the estimate to be higher than previous ones,” said LaRue, who began her Antarctic research career with the University of Minnesota’s Polar Geospatial Center For example, she said, all the colonies in Amundsen Bay in East Antarctica were fairly large colonies new to science, although many were previously hypothesized to be in existence. On the other hand, Lynch, who works in a region where populations of Pygoscelis adeliae have been decreasing due to climate change, was a little shocked by the jump in the overall population. About half of the increase, she noted, was due to the discovery of new colonies, many of which the scientists think are newly colonized territories. “That aspect, that we would find so many new potential Adélie colonies not previously described, is definitely a surprise given how much research has been done on the Adélie penguin over the last century,” Lynch said. Satellite data from the emperor penguin study challenged the long-held belief that Aptenodytes forsteri were philopatric, meaning they would return to the same location to nest each year. LaRue, Lynch and their colleagues, including emperor penguin expert Gerald Kooyman The research is not the first to suggest that penguins are less loyal to their colonies than first believed. A long-term study of Adélie penguins in the Ross Sea The work by LaRue, Lynch and their colleagues follows at least two other studies on emperor penguins this year. In January, in the journal PLOS One, scientists reported that they discovered, also through using satellite imagery, that some emperor penguin colonies had moved from their traditional breeding grounds on annual sea ice to thicker floating ice shelves when conditions caused sea ice to form later than normal. A more recent study in June, published in Nature Climate Change, suggests that emperor penguins may be in jeopardy in the future from climate change, as their traditional breeding habitat on sea ice disappears. The paper predicted population declines of more than 50 percent in some cases.

Photo Credit: Paul Ponganis

An aerial view of emperor penguin colonies at Cape Colbeck near the Ross Ice Shelf. Satellite imagery may eventually replace the need — and expense — of surveying Antarctic animal populations from aircraft.

At the surface, it would seem the studies are sending mixed messages, but Lynch and LaRue argue that the picture is just more complex than first believed. They hope their work will help scientists monitor future changes in these species and facilitate even better models forecasting future abundance and distribution. “Population declines that threaten the persistence of a species are right at the top of a conservation biologist’s biggest concern, and from that perspective, these two species appear to be in better shape than we may have thought previously,” Lynch said. “On the other hand, this does not speak to forces that may shape their future, and it does not speak to their ultimate fate responding to long-term climate change.” For example, the increase in Adélie populations in the Ross Sea, some scientists have argued, may be due to less competition for prey from the Antarctic toothfish, a large, long-lived species that is fished commercially under the more benign-sounding name Chilean sea bass. “I would argue that we now have a baseline from which we can gather data on future trends,” LaRue said. “These results won’t affect my level of concern for conservation, because I feel like we’ve just now gotten to a point where we know how the global population of emperors and Adélies are doing. “The exact impact that climate change and fishing has on the global population – and decoupling the two – has never before been quantified, and we need to figure that out first before any concerns can be quelled,” she added. NSF-funded research in this article: William Fagan and Heather Lynch, University of Maryland, Award No. 0739515 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |