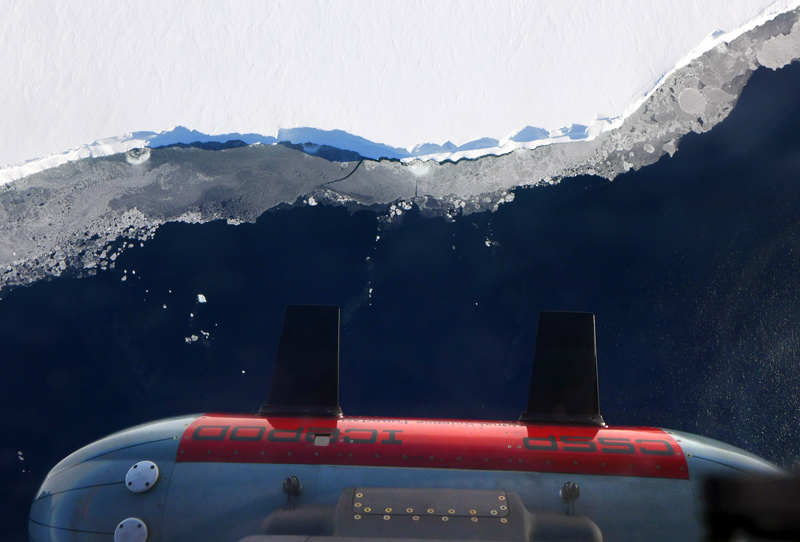

Good things come in small packagesIcePod bundles together a suite of instruments designed to measure Antarctica's icePosted June 8, 2015

The U.S. military has a long history of supporting research in Antarctica, particularly beginning in the 1950s with the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a campaign that kicked off the modern scientific era in the polar regions. The New York Air National Guard (NYANG), which flies the unique ski-equipped LC-130 Hercules in both Antarctica and Greenland, has taken that support more literally with a new project called IcePod Led by scientists from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) at Columbia University in New York, IcePod bundles together a suite of instruments into a capsule designed to fly on the outside of an LC-130. The instrumentation, including radars, lasers and high-tech cameras, will provide new details about structures above, within and below Antarctica’s ice-covered surface. “We’ve taken a cargo-hauling LC-130 and made a science platform that is roll on-roll off capable with any of our LC-130s that are out there,” said Maj. Joshua Hicks, a pilot with the NYANG’s 109th Airlift Wing who is involved with integration of IcePod with the airframe. The pod is a bit like a super-sized cargo carrier for a car rooftop at nearly three meters in length and almost a meter wide. Three bays inside the capsule hold various instruments, with space for more sensors in the nose cones located on either end. The IcePod concept is an alternative and complementary way to do the sorts of airborne surveys of ice sheets and glaciers that are usually done with aircraft dedicated for that purpose, according to Nicholas Frearson, senior engineer for the IcePod project with LDEO. “The plane is dedicated once it’s done because it’s totally full of gear,” he explained. The radars and associated instruments used in other types of airborne research not only fill the interior of smaller aircraft like a Twin Otter, but they also make use of the airframe itself including the wings. If a plane breaks, that’s the end of the project – or at least a significant delay. Once outfitted with instruments, the plane can’t be used for other missions. On the other hand, IcePod can be swapped from one Herc to another in a day, without the need for dedicated flights. A typical three-hour flight between McMurdo Station and Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station to deliver fuel and cargo could also collect science data along the way. “You can turn Pole tanker runs into science missions,” noted Robin Bell, IcePod principal investigator from LDEO. In fact, that’s exactly what happened in November on a late-night flight between the two U.S. research stations. The early returns on the data already hint at IcePod’s potential, as it provided some tantalizing clues about the structure of the Texas-sized Ross Ice Shelf, the largest of the so-called corks that keep Antarctica’s ice bottled up. Pop the cork – melt or weaken the ice shelf – and glaciers will flow faster to the ocean, raising sea level. “It’s much more rugged under there, which is going to matter for how warm water gets to the edge of the ice sheet,” Bell said. “You can really see the structure of the ice shelf. It’s really beautiful.” Imagery from a new type of infrared camera developed at LDEO also has the team excited. Its ability to identify miniscule differences in temperature can spot crevasses, or cracks in the ice, that aren’t always identifiable at the surface. Bell described the infrared signature as a “tendril” emerging from the colder interior of the crevasse to the surface. “We’ve been after that one for a long time – can we actually see crevasses that you couldn’t see otherwise,” she said. The crevasse detection capability of the infrared camera is also of interest to the NYANG, according to Hicks. While the Air Guard is testing its own radar system to detect crevasses, pilots often rely on visual clues from low-altitude flights over potential landing sites.

Photo Credit: Robin Bell/Columbia University

A gravity meter is loaded onto the LC-130. Gravity measurements are a way to discern certain features such as mountains or basins because will be slight differences in gravitational pull depending on the mass below the plane.

The idea for IcePod dates back to the 2007-08 International Polar Year (IPY), a global scientific campaign that followed the IGY 50 years later. Bell, Frearson and colleagues helped lead an effort to study a mountain range the size of the Alps buried within the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. Establishing a field camp on the high-altitude plateau from where a Twin Otter could fly its sensor suite over the subglacial Gamburtsev Mountains required more than 30 LC-130 flights. It would have been easier and cheaper to outfit a Herc with similar instrumentation. The caveat was that it had to be done without altering the airframe. “We thought we could take all of these sensors and actually shrink them down to a much smaller package if we’re very careful about it,” Frearson said. The National Science Foundation agreed the concept had merit, providing about $5.5 million in grants since 2010 to develop and test IcePod. Several tests have already been conducted in Greenland, but this is the first year IcePod has been flown over the Antarctic. Frearson said Antarctica is a harsher, colder climate for trials of the system. Recently, the team also started testing an external gravity meter that could also be miniaturized and plugged into IcePod. Gravity measurements are a way to discern certain features such as mountains or basins. For instance, there will be a slight increase in gravitational pull over a mountain range due to its additional mass. “There is a huge range of things we can use [IcePod] for,” Frearson noted. “The whole of this thing is modular.” For the 109th Airlift Wing, IcePod represents an opportunity to work more directly on the research the Air Guard has supported since the 1996-97 austral summer, as well as stretch its own capability in new directions. “I don’t think you’ll find many other units that have to worry about testing new equipment on an aircraft,” Hicks said. “It’s out of the standard norm.” NSF-funded research in this article: Robin Bell, Nicholas Frearson, Christopher Zappa and Michael Studinger, Columbia University, Award No. 0958658 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |