El Niño in AntarcticaPosted October 28, 2015

If the weather at the bottom of the world seems a little out of whack this year, blame El Niño. “The main area of impact in all of Antarctica for El Niño is right along the West Antarctic coast up to the peninsula, with the peninsula warming,” said Lee Welhouse, a scientist in the Antarctic Meteorological Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “[In] The Amundsen-Bellingshausen sea region you can expect higher pressures which will cause warming in the peninsula.”

Photo Credit: Geordan McQuiston

It’s been a stormy start to the season because of El Niño. Workers out on the sea ice get hit by bad weather building a “RobotHut.”

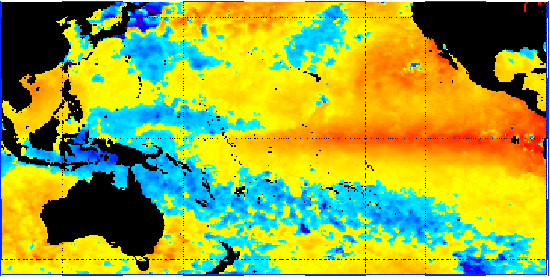

Welhouse will be right on the front lines to see the weather changes that El Niño will bring to the continent. He is deploying in January as a participant in the National Science Foundation-managed U.S. Antarctic Program. “I’m concerned that there will be poor weather in West Antarctica this year, more storms, more clouds, more everything than usual just because you have a different setup in the area that’s changing the wind regime,” Welhouse said. “All it takes is a little bit of the wind from the wrong direction pulling clouds into West Antarctica and you can’t fly and it becomes much more difficult to do work.” However Welhouse cautioned that because forecasting the weather is complicated, it’s difficult to make any definitive predictions about El Niño’s effects. Its epicenter is in the tropics, thousands of miles away from the Antarctic coast, so there are many ways for its influence to be diluted across the ocean. “If you look back at the strong El Niños in particular, the early ‘80s El Niño had a very different impact from the El Niño that happened in ’97 to ’98,” Welhouse said. “One of them had a strong impact. You saw a lot more storms through West Antarctica; you saw things as far away as McMurdo, while the other had little to no impact.” Eric Steig, an NSF-funded glaciologist at the University of Washington, studied how historically El Niño affected the continent. “It’s been known for some time that El Niño has an influence on Antarctica, especially West Antarctica,” Steig said. Every few years, the ocean around the eastern and central Pacific warms a few degrees, disrupting weather patterns across the ocean from Alaska to Antarctica. Scientists at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration are predicting that this year’s El Niño will be a particularly strong one. They announced in early September that they expect it to last into 2016 and that the June-August temperatures in the Pacific were already the third warmest since records started being kept in 1950. “In general when you have strong El Niños, you tend to have warmer temperatures and more precipitation over West Antarctica,” Steig said.

Photo Credit: Lee Welhouse

Lee Welhouse will be updating part of the Antarctic Automatic Weather Station network, like this in West Antarctica, the region most likely to be affected by this year’s El Niño.

The effects of El Niño should be widespread across the region, but they may not necessarily be identical in all areas. Most of West Antarctica will warm, but there’s a good chance that the area around McMurdo Station will cool down some as a semi-permanent low-pressure system moves in from the Ross Sea. Since July, much of the western side of the continent, including McMurdo, has been battered by severe weather, another likely effect of El Niño. “It has been a stormy spring,” said Mike Carmody, the Antarctic Program’s Meteorological Operations Manager. “Any strong El Niño season you’ll have a stormy spring.” One complicating factor is that the effects of El Niño seem to vary a great deal depending on where the greatest warming occurs in the Pacific. The warming patch of water can form along a band ranging from the central Pacific to the eastern Pacific but it’s not yet clear where this year’s El Niño will ultimately center around. “Central Pacific El Niños have a larger impact on West Antarctica,” Steig said. Predictions are further complicated by a general lack of data from the region. El Niño only occurs every few years and direct records of it only go back until the 1950s. Detailed data on West Antarctic weather extends only to the late 1970s when weather satellites first started to provide regular coverage of the continent. Steig and his research team have been able to extend the data back somewhat using ice cores and oxygen isotopes as substitutes for temperatures, but he adds that it’s not a perfect system for going back a long way. “That’s harder because you’re getting further and further away from what you really know firmly, which is the modern situation,” Steig said. “I would say it’s a work in progress to use the ice cores that way.” Steig said also that in El Niño years, there is evidence for increased ice melt where the West Antarctic Ice Sheet meets the ocean. This arises from changes in the ocean, driven by the same changes in weather patterns that bring in more storms. “El Niño events tend to change the local wind direction along the Amundsen Sea coast of Antarctica,” Steig said. “This happens to push the ocean in a particular way so that you got more of the warm deep ocean water coming up under the ice shelves.” NSF-funded research in this article: Matthew Lazzara, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Award No. 1245663 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |