Weighing Seals Without ScalesPosted December 2, 2015

Thousand-pound seal moms don’t much like being herded onto scales to be weighed, but they don’t seem to care about having their picture taken.

Photo Credit: Jay Rotella

PhD student Terrill Paterson (left) and field researcher Erika Nunlist gather data about a seal and her pup at the Turtle Rock seal colony.

Scientists working on the longest-running Antarctic seal population study are using a new technique that needs little more than an off-the-shelf digital camera to turn photos of Weddell seals into important new data in their continuing research. The research is supported by the National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. The ongoing Erebus Bay Weddell Seal Population Study has been tagging and tracking seal populations around McMurdo for almost half a century. “We’re trying to understand how many animals are in that population and how that’s changing over time,” said Jay Rotella of Montana State University, one of the co-principal investigators for the project. “And within that population, we’re trying to understand the lives of individuals and why some live longer and produce more offspring than others.” This year, they’ve started using a new technique called stereo photogrammetry to weigh seals without ever touching them. “The idea is you’re doing metrics with photos,” Rotella said. Kaitlin Macdonald, a master’s student at Montana State University has been spearheading the effort to glean the mass of a mother seal with a camera. Stereo Photogrammetry

Images Courtesy: Kaitlin Macdonald

1. Researchers surround a mother seal with specially designed measuring sticks and take pictures from all angles.

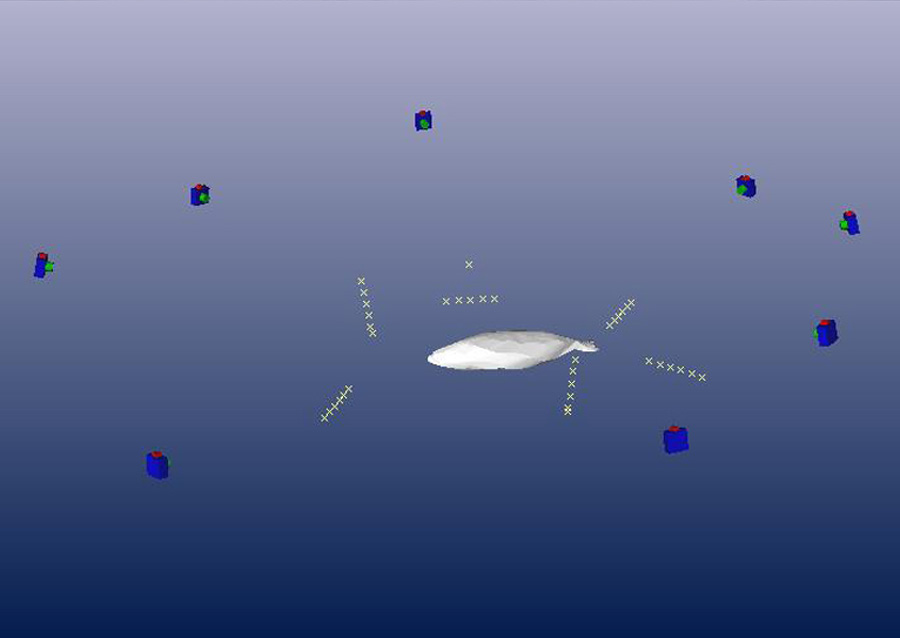

“We can take photos around the female seal,” Macdonald said. “You create a 3-D image of the seal from all the photos that you take, so you can get a volume estimate from that 3-D model of that seal.” After photographing the seal from all sides, they feed those images into a computer program which analyzes where the seal’s edges are in each photo. It stitches all of those contours together, producing a virtual reproduction of the aquatic mammal. “It basically makes a 3-D wireframe model of the seal,” Rotella said. It’s a technique already used in research ranging from archeology to topography to make virtual models of artifacts or terrain respectively. Rotella’s team then takes it one extra step. Knowing the seal’s total volume, it’s a simple matter to multiply that by the average density of a seal to deduce her total mass. They had been testing the technique in the field in the last few years, but this is the first time they’re integrating it directly into their research. “The beauty of this photography work is we can now go and estimate weight loss of mothers,” Rotella said. “How much weight did the pup gain and how much weight did the mother lose?” It’s a question that gets to the core of understanding how a seal’s health affects her offspring. Weddell seal mothers devote themselves to raising a fit pup, but producing huge quantities of milk takes its toll. “Females lose approximately 50 percent of their mass while they’re nursing their pup,” Macdonald said. “So they’ll typically come in around 1,000 pounds and we think they typically leave at 500. But we’ve never been able to weigh those females.” It’s likely that older females lose more weight and give birth to smaller pups than younger moms, but that’s difficult to quantify definitively. Putting a 50-pound newborn pup on a scale is relatively easy; doing the same with a half-ton expectant mother has been anything but. This adds a new dimension to an already extensive population dataset. Researchers started studying McMurdo Sound’s Weddell Seals in the late 1960s and tracking individuals in the 1970s.

Photo Credit: Jay Rotella

A curious pup investigates the researcher’s camera at the Turtle Rock Weddell seal colony.

“What we do is go out and find every pup that’s been born in the study area, give it a tag, make sure that we write it down, enter it into a field computer and then we put it into this giant database that’s maintained by the project,” said Ross Hinderer, a field technician from Montana State University. Now well into its fourth decade, the project’s database amounts to a nearly complete family history of all the seals born in the area and where they’ve been spotted. “We’re interested in who’s coming here, who’s born here and who’s returning here,” Macdonald said. “We’re also looking at the vital rates of the animals: how many pups a female has, their survival rates, what’s the survival rate of a pup to adulthood and then what’s the survival rate of an adult.” The project’s longevity lets them see how seals react to changes in their environment. From the early 1970s through the 1990s, seal births were relatively stable at about 450 pups per year. Then in 2002, icebergs blocked the mouth of McMurdo Sound, preventing much of the sea ice from clearing out in the summer. This had a huge impact on the seals, and 2004 saw the fewest pups on record. Starting around 2007, after the icebergs broke up and the usual summer sea ice cycle returned to McMurdo. The number of seals born in the area started to swing dramatically, and now the researchers are seeing many more than before. This year, the team recorded more than 650 seal pups born, shattering the former record of 608. “The last five years or so, it’s been very high pup production,” Rotella said. “This year was the highest since 1967.” At this point they’re seeing the third generation of seals in the study return to the favorite spots around the area to raise their young. “Multigenerational studies don’t really happen very often in biology,” Hinderer said. “It’s really essential for something like population biology where you want to look at what sorts of animals produce the best offspring.”

Photo Credit: Ross Hinderer

Field researcher Erika Nunlist enters a seal's tag number and vital statistics into her data book and field computer.

Keeping tabs on them is relatively easy because when it comes to pupping, Weddell seals are creatures of habit. Females tend to be faithful to a couple of spots around McMurdo Sound, and will come back year after year to give birth there. A big factor is simple logistics. They need to be able to climb out of the frozen sea through cracks in the ice and so have established colonies near where big cracks usually form. For the scientists, Weddell seals can easily be found all over the sound on the firm sea ice, as opposed to Ross or crabeater seals that tend to live farther out on the less stable pack ice. Unlike the leopard seals, Weddells are docile, and don’t mind researchers approaching and tagging them. “Ultimately what we have is an animal that really lends itself to being studied,” Rotella said. The population in Antarctica also affords researchers a peek at wildlife that hasn’t been disturbed by human development. “This is a relatively pristine environment, one of the last on Earth,” said Eric Boyd, a field technician from Montana State University. “This opportunity isn’t available elsewhere because we can see how they’re doing before we start impacting them.” More information about the seals, the science, and the project including videos, field blog, articles and publications and audio files can be found on the project's website NSF-funded research in this article: Jay Rotella, Donald Siniff and Robert Garrott, Montana State University, Award No. 1141326 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |