Sea DriftersResearchers Spend a Summer at Palmer Station Studying How Warming Oceans Affect the Antarctic Food WebPosted March 6, 2018

The menagerie of drifting ocean creatures that lives off the coast of Palmer Station was under the microscope more than ever this past austral summer.

Photo Credit: Deborah Steinberg

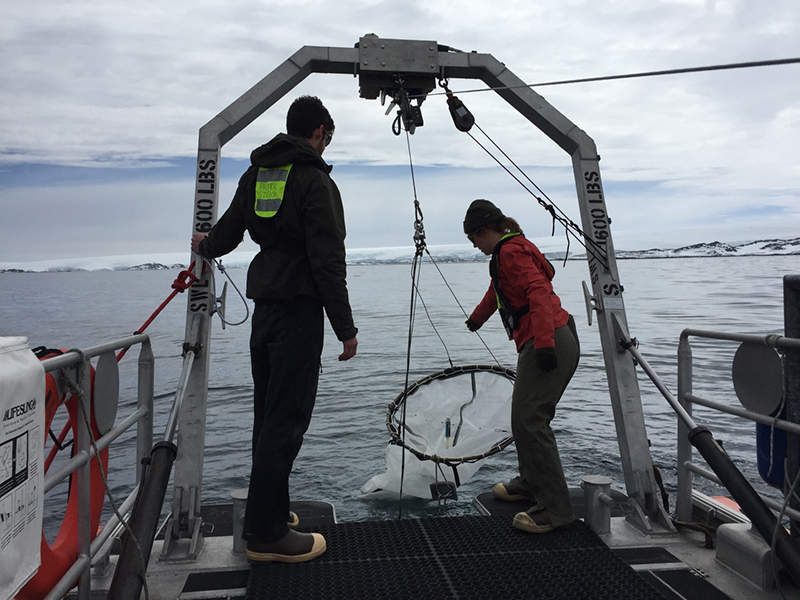

Researcher Jack Conroy (left) and technician Leigh West deploy a net off the back of one of the RHIBs.

A team of scientists spent five months at the station studying the tiny creatures that drift along the ocean currents. It’s the first time the research team studying these zooplankton spent an entire field season at Palmer Station analyzing changes over time in the abundance of different species. “We really wanted to have a seasonal study so that we could see how the near-shore zooplankton community changed over the course of the spring into the late summer early fall,” said Deborah Steinberg, a professor of marine science at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) and principal investigator on the krill project. Understanding the food web along the Antarctic Peninsula, the part of the continent that juts upward toward South America, has never been more critical. The region has been undergoing significant changes. “The western Antarctic Peninsula is one of the most rapidly warming regions on the planet, we’ve seen a long-term decline in sea ice in the region,” Steinberg said. “The sea-ice season has been reduced by about three months on average since the 1980s.”

Photo Credit: Deborah Steinberg

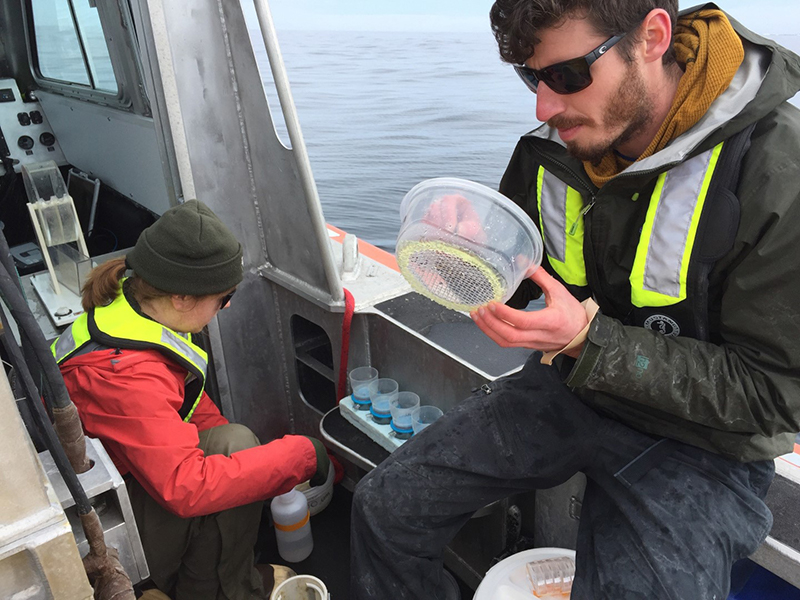

Researcher Jack Conroy (right) and technician Leigh West analyze some of the zooplankton they caught.

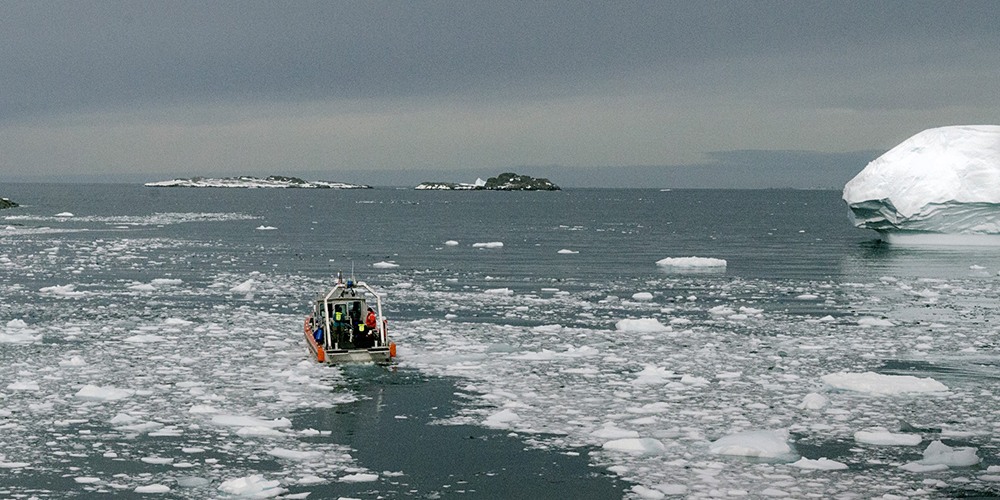

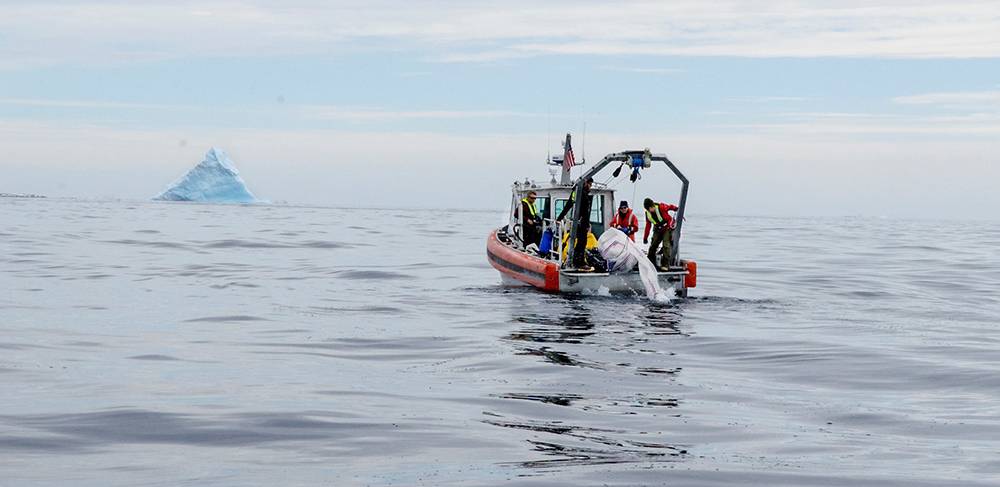

Climate projections predict that this warming trend is likely to continue, and the ice cover will continue to decline. The creatures that call this region their home rely on the annual sea ice to survive, so as the sea ice declines, it’s likely to have a significant effect on the entire ecosystem. “We want to figure out how the changing climate is influencing the ecosystem and the poles essentially serve as a bellwether for that because this is one of the areas that’s undergoing change the fastest,” said Jack Conroy, a VIMS graduate student. “So, to get at that, we need to understand the middle of the food web, which is the role that krill and zooplankton are filling.” Ordinarily, the researchers sail in January on one of the research vessels operated by the National Science Foundation-managed U.S. Antarctic Program. Their NSF-funded research study site comprises a 700-kilometer-long section of the peninsula, where they take samples along a grid that extends several hundred kilometers off the coast. However that only offered them a snapshot of the creatures during a single month of the year, as opposed to a longer, seasonal look at species succession. Zooplankton are marine animals that drift with ocean currents. Though often microscopic, they include creatures as large as jellies, krill that grow as big as shrimp, and salps–another type of gelatinous invertebrate. These species make up a central part of the food chain, feeding on microscopic plants called phytoplankton. At the same time, they’re food for larger marine animals including fish, penguins, seals, and even whales. “Understanding the dynamics of these animals is important for understanding how energy gets passed up the food web,” said Conroy. Steinberg and her team are part of NSF’s Long Term Ecological (LTER) Research Program at Palmer Station, that has been studying the marine ecosystem around the station since the early 1990s. Different groups associated with the LTER program focus on nearly every part of the area’s ecosystem, ranging from microscopic bacteria and phytoplankton, to large marine animals like whales and penguins. “The beauty of the Palmer LTER is we have all this other excellent information to put our study in the context of,” Steinberg said. “We have, at Palmer Station, phytoplankton measurements from our colleagues, and we have measurements of the physical water column–like temperature and salinity, and the amount of ice the preceding winter and the species of phytoplankton. So, we have all this great information to place this seasonal study of zooplankton into context and use that seasonal study to inform our larger grid study which is one time of the year.” During the austral summer, most of the Palmer LTER groups stay at the station, traveling by small boat around the bay and to nearby islands to make their observations and collect samples. However, sampling zooplankton requires heavier equipment than the small inflatable boats could easily handle. This year is the first operational season for the station’s burlier new Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats, or RHIBs, named Rigil and Hadar. Bigger than the previously used inflatables, and equipped with strong winches and powerful engines, the boats can easily drag the one-meter-square, mesh nets needed to collect zooplankton through the water.

Photo Credit: Marissa Goerke

Technician Leigh West uses a caliper to measure the sizes of the recently-caught krill inside the cabin of the RHIB Rigil.

“It was difficult to do zooplankton sampling form the small boats that were at Palmer,” Steinberg said. “Now that we have these rigid hull inflatable boats, we can actually do this a lot easier.” After reeling in the nets, the researchers spent hours hunched over microscopes identifying and counting every creature that they pulled in. By taking a census of all the different kinds of zooplankton, analyzing what they’re eating and how large they are, the team can learn a lot about the overall health of the food web in the area. While they’re trolling for zooplankton they’re also using other, higher tech tools such as acoustics, to analyze the ocean around them. “Essentially, it’s an echo sounder on the bottom of the boat that’s constantly pinging out sound waves,” Conroy said. “It’s calibrated so that when that sound bounces back, the same way you would use a fish finder, we can detect krill that way to make a better measurement in case you’re missing animals with the net.” As the sea-ice level has declined in recent years, krill are at particular risk.

Photo Credit: Peter West

The a-frame on the back of the new RHIBs allows the researchers to deploy their big nets off the boats.

“Krill depend on sea ice,” Conroy said. “When they’re in their larval stages they feed by scraping algae off the bottom of sea ice.” Without sea ice, the krill would likely find it more difficult to thrive and compete against other warmer- and more open-water adapted species like salps. Already, scientists working in warmer regions north of Steinberg’s research grid have reported declining krill populations. “As the climate continues to warm, we haven’t seen it yet, but were expecting probably in the near future to see decreases in the Antarctic krill in our study area too,” Steinberg said. “We have some hypotheses about what’s going to happen here in the future based on how we know changes occur from year to year depending on ice conditions.” It’s an issue with impacts that would extend beyond the waters of the Southern Ocean, which support important fisheries. “Some of the species down there, zooplankton, are food for commercially important fish and they themselves are also commercially fished. Antarctic krill is commercially fished,” Steinberg said. The research team is still analyzing the many samples they took this season and are planning a return to Palmer next summer as well. NSF-funded research in this story: Deborah Steinberg of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Award No. 1440435. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |