Larvae La Vida LocaHow Will Warming Oceans Affect Young Invertebrates When They're at Their Most Vulnerable?Posted January 6, 2020

As oceans warm around the world, the creatures that live in them are feeling the effects.

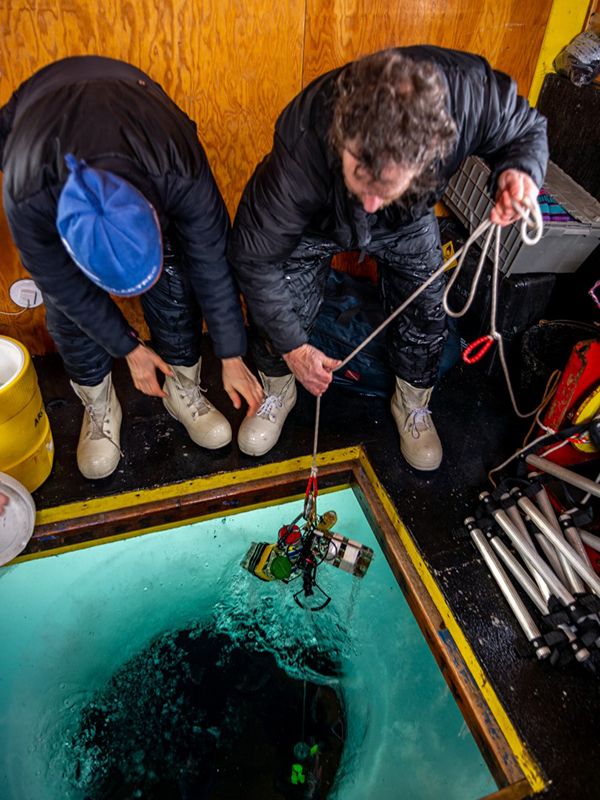

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Amy Moran (top left), Steve Rupp (top right), Rob Robbins (bottom left) and Aaron Toh prepare to dive through a hole in the sea ice to collect invertebrate eggs.

In regions like the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica, which has been unchanged for millennia, researchers worry that even small fluctuations in water temperatures can have major effects on the marine ecosystem. A team of scientists working at the National Science Foundation's McMurdo Station have been looking at what is likely to happen in the face of such changes to some of the ocean-dwelling critters when they’re young and at their most vulnerable. "We're focusing on invertebrates; basically everything except fish and seals and penguins. We're particularly interested in invertebrates because there's such a wide diversity of them," said Amy Moran, a marine biologist at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa and principal investigator on the project.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

The research team dove and collected samples from sites around McMurdo Sound, including this site near Turtle Rock.

Drawing on research on similar critters in other parts of the world, Moran thinks that warming waters could have complicated effects on the growth and development of invertebrates. Likely, the higher temperatures will increase their metabolisms and actually cause them to mature faster in their egg. "The warmer temperatures has shown that it's speeding up their development," said Graham Lobert, a graduate student at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. "We're seeing the rates of things not going right, not dividing right, occurring more often at higher temperatures." The research is supported by NSF, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. Water temperatures around McMurdo Sound hover at a consistent minus 1.8 degrees Celsius, with only fractions of a degree variation between summer and winter. It's been this way for millions of years, and the critters that live in these waters have evolved to depend on this stability. As the planet heats up, the seas will warm, possibly by several degrees, threatening the marine life in the Southern Ocean that can't cope.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Aaron Toh (foreground) adjusts his scuba tank as he prepares to dive with the research team and USAP staff divers to collect samples from the seafloor.

"We don't know how vulnerable they're going to be, but they're going to be very strongly affected by small changes in temperature that really wouldn't matter much in the short term to a temperate or a tropical species," Moran said. "A one-degree temperature change in Hawai'i is like nothing to an animal, it's like a wave comes in and there's a several degree change right there. But in the Antarctic, that's pretty dramatic." Moran and her team are investigating how warmer waters affect the development of newly-hatched juvenile invertebrates, animals which lack backbones, as well as embryos still in the egg. Similar research has been conducted on young fish, but Moran is focusing on the warming’s effects on invertebrates including sea spiders and nudibranchs. "Most of these embryos that we're going to be looking at will be fueling their development and their growth by yolk reserves when they're in the egg," Moran said. "It's sort of like the rate that they burn their gas, the rate that they burn their yolk up, to both build new structures and to provide the energy to build those new structures. That will be affected by temperature." The other downside is that they’re optimized to mature at a particular rate, and growing faster will likely take more energy and require them to consume their yolk reserves faster than they would otherwise. At the end of their gestation, these speed growers could emerge from their eggs smaller or not fully mature.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Amy Moran (Left) and USAP diver Rob Robbins haul up the eggs and other samples they collected while diving on the ocean floor.

"It might not kill them during development, but they might enter the adult habitat in worse shape," Moran said. "They could be too small to eat whatever they're supposed to be eating, or they could be subject to predators, or starve to death." This juvenile stage, just after emerging from their eggs, are when many invertebrates are already at their most vulnerable. They're still small enough to be prey for many predators, while still not large enough to properly forage for themselves. Many already don't survive this period of life, and piling on additional handicaps from a rushed or incomplete development could put more at an additional competitive disadvantage. To see how they're affected, Moran and her team are diving beneath the frozen surface of the ocean around McMurdo Station and gathered eggs, transplanting them into incubators to let them mature under different ocean conditions.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

In the aquarium at McMurdo Station, Amy Moran tends to a tank of sea spiders. Different tanks are kept at different temperatures to simulate a range of potential future ocean temperatures.

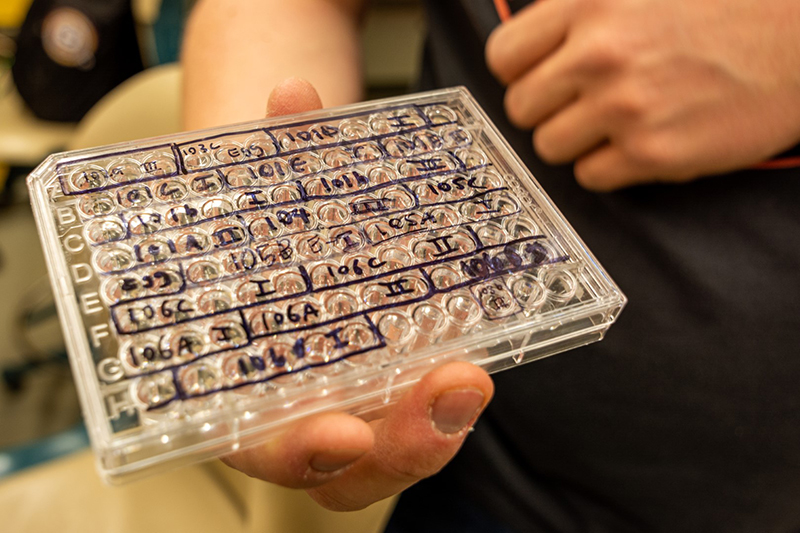

"We're going to collect embryos in the field at different times of the seasons, and we're going to stage them in the lab and then put them in controlled temperature environments, over a fairly tight range of temperatures. We're going to do ambient, which is minus 1.8, to 4 [degrees Celsius]," Moran said. "We're going to raise them, we're going to follow them, we're going to watch them, we're going to look at them we're going to stage them and see how fast they're developing though their different stages." Over several weeks, the team has been checking on the developing embryos to record how well they're doing and whether there are any clearly visible abnormalities in their growth. "We can measure their size and we can measure the time it takes for them to reach each stage of development. And then we can look for abnormalities," Moran said. "A nice healthy embryo is symmetrical and all the cells are matching and the same size and in an unhealthy one they're not."

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Graham Lobert shows off the specimen case where sea spider embryos are kept at simulated ocean temperatures to track their development.

They're focusing on a few different species including giant sea spiders and two species of nudibranchs, a kind of slug-like mollusk. Nudibranchs lay their eggs on top of rocks in long gelatinous tubes that a trained diver can easily spot. "Male [sea spiders] carry the eggs… You can pluck them right up, pull the egg off without injuring the male, and you're able to put them back," Lobert said. "They're really interesting down here because they carry large egg masses so it's really easy to count how many eggs they have or how many individuals you have in that egg mass." In addition, the team is returning to McMurdo Station in late January to investigate how the changing seasons might be affecting the development of invertebrate embryos and juveniles. Though the water temperatures of the region are remarkably stable over the year, there are some subtle changes between summer and winter.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

Graham Lobert uses a microscope to tracks the development of sea spider juveniles and embryos to see how they grow under different ocean temperatures.

"There actually is about a slightly less than a degree difference in water temperature between the end of winter, and the spring/summer where it's about a degree warmer and there's also lots more oxygen in the water," Moran said. "That's kind of the natural experiment. Does that one degree in difference make a difference to the embryos?"

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

In addition to sea spiders, the team is studying the effects of warming temperatures on the young of nudibranchs and other invertebrates.

Most research on the effects of changing sea temperatures has been conducted on species collected during the Antarctic spring when the sea ice over McMurdo Sound is strongest and it's easiest to work off of to collect samples. This year the team will return to collect samples during late summer, after the waters have been their warmest. They've also been deploying data loggers around McMurdo Sound to track how the water temperatures and oxygen levels change over the seasons. This is the first of two field seasons to collect samples for their project. "It's been going good. We've got lots of animals, diving's been going really well," Moran said. NSF-funded research in this story: Amy Moran, University of Hawai'i at Manoa Award No. 1745130. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |