Forever chemicals lingering in Antarctic marine mammalsOne of the largest studies ever on pollutants in Antarctic marine predators finds the animals are still being exposed to environmental contaminantsPosted March 28, 2022

New research finds Antarctic seals and killer whales still have persistent organic pollutants stored in their blubber, despite many countries having phased out production of these toxic chemicals, some as long as 50 years ago. In crabeater seals in particular, the concentrations of some chemicals are high enough that the researchers suspect the pollutants might be affecting the animals' health.

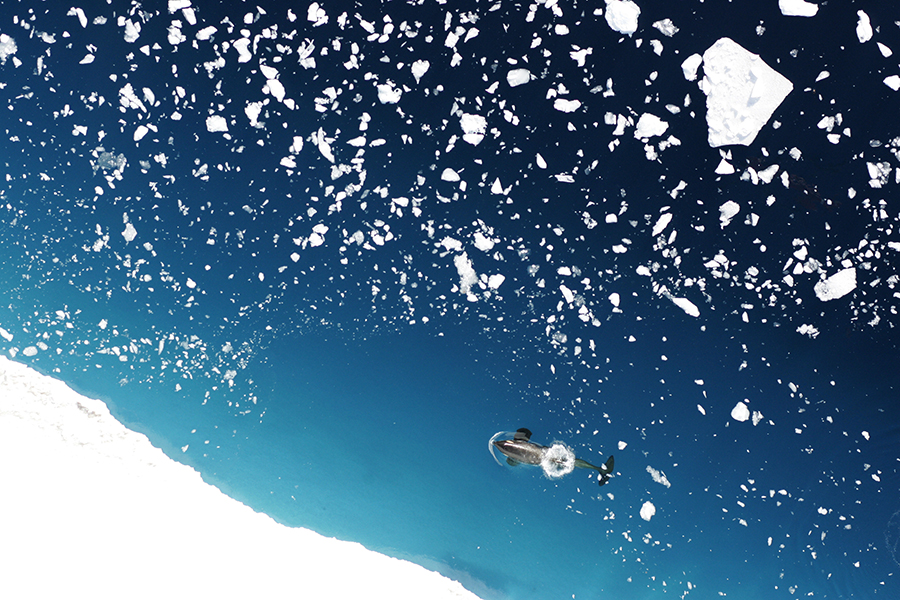

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

A Weddell seal peers over a ridge of ice in Cierva Cove along the Antarctic Peninsula. Though awkward on land, Weddell seals are graceful swimmers and can hold their breath underwater for nearly an hour and half.

The new findings add to the growing body of evidence that Antarctica is not as pristine an environment as once thought and show that ‘forever chemicals' can make it even to the most remote regions on Earth. Antarctica doesn't have as many contaminants as the Arctic does, but it's still a cause for concern, according to Rainer Lohmann, an environmental chemist at the University of Rhode Island and lead author of a new study detailing the findings. “In the Arctic you see animals with deleterious health effects because of these pollutants, but in the Antarctic it's not as obvious,” Lohmann said. “Here there's some indication of that, but it's nothing like you see in the Arctic.” The pollutant problemAntarctica had long been considered a pristine environment because it's so far away from human populations and sources of pollution. But this changed in the 1960s, when researchers found pesticide residues in Antarctic waters and animal tissues. Scientists have studied pollutants in the Antarctic ever since, looking for the presence of contaminants in Antarctic snow, water, plants, and animals. Many of the contaminants they look for are persistent organic pollutants, commonly known as forever chemicals, which take years to break down in the environment. These include synthetic pesticides like DDT, compounds called PCBs that were once used in electronics and other industries, and flame retardants called PBDEs used in many types of products. In the new study, researchers measured the concentrations of pesticides, PCBs and PBDEs in Antarctic killer whales as well as Weddell, Ross, and crabeater seals. These chemicals are highly toxic and can damage or disrupt an animal's reproductive, endocrine, immune, or nervous system. Most forever chemicals are fat-soluble, so they easily accumulate in the thick layers of blubber Antarctic mammals use to store energy and keep warm. The chemicals also get more concentrated as they move up the food web, so top predators like seals and whales are likely to have the greatest concentrations in their tissues and are at the greatest risk of toxic health effects. Toxins in blubberThe researchers analyzed skin and blubber samples from three killer whales and 77 seals that were collected during two cruises to the Amundsen and Ross Seas in the austral summers of 2008-2009 and 2010-2011. They found there are still significant concentrations of forever chemicals in the animals' blubber, even though many countries have banned or phased out production of the toxins since the 1970s. The three killer whales sampled had much higher concentrations of toxins than the seals, which makes sense because they're higher up in the food web, Lohmann said. For seals, concentrations of the toxins are lower than they were in previous studies, but concentrations in whales seems to have remained the same over the past several decades. The results show higher concentrations of toxins in female crabeater and Ross seals as opposed to males, but the opposite was true for Weddell seals. Male and female seals have separate foraging areas and metabolic rates, so it's not surprising there were different toxin levels between the two sexes, according to the researchers.

Photo Credit: Mike Lucibella

A crabeater seal reclines on the boat ramp at Palmer Station. Despite their name, crabeater seals only eat tiny krill, using their specially shaped teeth to filter out seawater.

Toxin levels were high enough in crabeater seals that the animals may be experiencing health effects as a result. The results showed crabeater seals were expressing certain genes associated with immune responses to pollutant exposure, meaning the toxins may be concentrated enough to be disrupting the seals' immune systems. Researchers don't regularly monitor pollutants in Antarctic animals the way they do in the Arctic, so it's difficult to say if the pollution problem will change over time. “What we cannot say in the Antarctic is whether things are getting better or worse, because there isn't regular monitoring to figure out if the worst is behind us, or if it's going to stay that way,” Lohmann said. “On the Arctic side you have regular monitoring, they do things every year. For the Antarctic it's a wild guess.” This research is supported by the National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. NSF-funded research in this story: Rainer Lohmann, University of Rhode Island, award 1332492. |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |