Graphic Credit: Lauren Lipuma

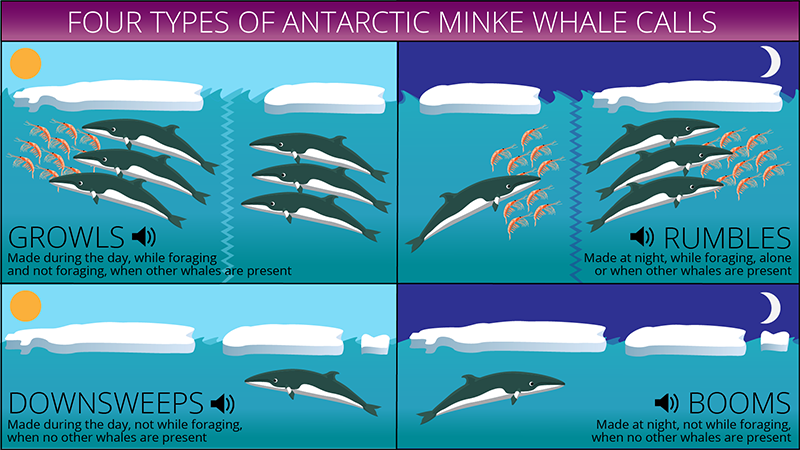

Click the graphic to hear recordings of Antarctic Minke whales. (Large Image)

Minke Whale Call - Growl (Looped)

Minke Whale Call - Rumble (Looped)

Minke Whale Call - Downsweep (Looped)

Minke Whale Call - Boom (Looped) Rumbles, booms and growls: Listen to the first recordings of these Antarctic whale callsNew research captures never-before-heard calls made by minke whales in the Southern OceanPosted October 24, 2022

Biologists are getting their first real listen to the vocalizations made by Antarctic minke whales, the most abundant yet least understood whale species in the Southern Ocean.

Photo credit: Amy Belcher.

Minke whales skim the surface of the ocean water near the Antarctic Peninsula. New research shows Antarctic minke whales are more social than scientists originally thought.

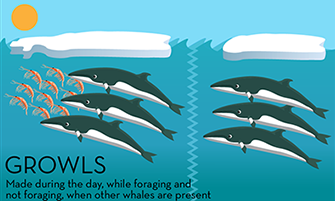

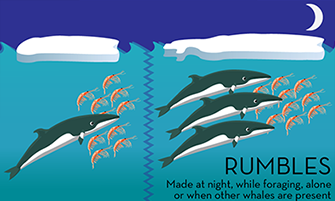

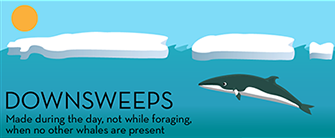

New audio and video footage, recorded by suction-cup cameras placed on individual whales' backs, shows scientists the range of calls made by Antarctic minke whales and sheds some light on what the calls are used for. The audio footage captured three new calls never before described in minke whales: booms, rumbles and growls. The video footage allows scientists to put the calls into social context for the first time, showing what the whales are doing as they make the different types of vocalizations. The recordings show Antarctic minke whales have a larger acoustic repertoire than previously thought, and some of their calls are strongly associated with specific behaviors and times of day. The footage also shows minke whales are much more social than scientists originally thought: they often swim and feed in groups of four to five animals. The results significantly boost biologists' understanding of minke whale behavior, which can help researchers understand how the animals will fare in a changing climate. “The better we can be about studying minke whales in the same way that we study humpback whales… it's going to give us another facet of how this landscape or seascape is changing and what that's going mean for the animals that are here,” said Ari Friedlaender, an ecologist at the University of California Santa Cruz and co-author of a new study detailing the findings. Calls of the wildAntarctic minke whales are the most abundant whale species in the Southern Ocean but have been difficult to study in the past. They're the smallest of the Antarctic whales, but they prefer areas of water with lots of sea ice, which helps them avoid falling prey to killer whales. It's difficult to navigate boats in waters choked with ice, so scientists have had a hard time studying minke whales in the past. But in February and March of 2018 and 2019, researchers successfully attached suction-cup satellite tags to the backs of 16 minke whales in two bays on the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula. This type of tag has just been developed in the past 10 to 15 years and is capable of recording audio and video footage while tracking a whale's movements and position in the water. (The whales aren't harmed by the placement of the tags). Video produced by Lauren Lipuma. Footage provided by Ari Friedlaender. Footage captured under NMSF permit no. 23095 and ACA permit no. 2015-011.

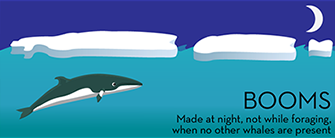

The researchers combined data from the satellite tags with drone footage and information from echosounders that map the locations of minke whale prey. For this study, they used over 140 hours of footage that recorded nearly 300 individual calls to put the whales' vocalizations into context. The recordings showed Antarctic minke whales make four distinct types of calls, three of which had never been heard before. Downsweeps, the one call type recorded previously, are continuous, low-frequency calls lasting only about a fifth of a second. The most common type of call recorded in the new study was a rumble, which sounds remarkably like a zipper. Booms are discrete, guttural calls emitted in bouts that last about four-fifths of a second, and growls are continuous roars that are higher-pitched than the other three calls and last about a half a second. Downsweeps and booms were made most often when the whales were alone, so the researchers suspect they use those vocalizations as contact calls - to get the attention of other whales in the vicinity. “This was one of the first times that vocalizations have actually been paired with some really interesting social data,” said Caroline Casey, a bioacoustics expert at the University of California Santa Cruz and lead author of the new study. “So for me, that was the most exciting part: seeing whether or not there were specific calls that were strongly associated with feeding and non-feeding or social and non-social behavior.” Solitary no moreMinke whales are generally thought to be solitary animals, but the new findings show they often swim and feed in small groups. The recordings show they make growls and rumbles when foraging for food, but the researchers are unsure whether these calls alert other whales to the fact that there's food available, help the whales coordinate feeding, or serve some other purpose. “There are vocalizations that the animals are likely using to help create or maintain that social cohesion,” Friedlaender said. “And so we went from an animal that we thought was just the single little whale that lives in sea ice to a community and a culture within their species.” There's a fifth type of minke whale vocalization called a bio-duck often heard during the Antarctic winter, but the researchers didn't hear that call in this study. It could be that the bio-duck is made mostly during the winter or that it's a mating call. Most marine mammals use sound to communicate, so the methods used in this study could be applied to other animals, according to the study authors. “Being able to pair what's happening from the animal's perspective with the sounds that they're making - this is applicable to any species of whale,” Casey said. “We're hoping that it presents a new mode of describing acoustic behavior for species that other people can adopt and use.” This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. NSF-funded research in this story: Ari Friedlaender, University of California Santa Cruz, award no. 1643877; Jeremy Goldbogen, Stanford University, award no. 1644209. All research was conducted under scientific authorizations from the National Marine Fisheries Service (permit no. 23095) and the Antarctic Conservation Act (permit nos. 2015-011 and 2020-016). No whales were harmed during the collection of this data. |