Weddell seal moms sacrifice diving capacity to help pups growTransferring iron to pups through milk reduces their ability to store oxygen and hold their breaths on long divesPosted November 21, 2022

Nursing Weddell seal moms transfer so much iron to their pups through their milk that they can't spend as much time underwater in the months after their pups are weaned, according to new research. Iron is a critical nutrient for all animals but is especially important for Weddell seals, as it allows them to store enough oxygen in their bodies to be able to hold their breaths on deep dives while foraging for food. A new study of Weddell seals in Erebus Bay, Antarctica finds nursing mothers transfer so much of their own iron stores to their pups that their diving capacity is greatly reduced for several months after their pups are weaned. The study found females who gave birth had roughly 25 percent shorter dives in the months after their pups were weaned than those who didn't give birth in the same year. Reduced diving capacity may not be life-threatening, but it's a cost of reproduction biologists hadn't considered before and may affect the moms' abilities to carry young in the year after they give birth, according to the researchers. “Even in humans, when iron stores go down a little bit, there are performance consequences,” said Jenn Burns, a biologist at Texas Tech University and co-author of the new study. “It's not necessarily a bad thing, it is part of the natural cycle in the animal, but it's a change in condition that we hadn't previously thought about that may impose constraints on what they can do and how they work in the environment.” Milk and ironWeddell seals are the southernmost breeding mammal on Earth and have a unique physiology tailored to life in the Antarctic. They can transport large amounts of fats through their bloodstream without suffering from cardiovascular disease and store a large amount of iron in their muscle tissue, which allows them to hold their breath for long periods of time.

Photo Credit: Michelle Shero. Image taken under NMFS permit 17411-03.

Weddell seals resting on sea ice in Erebus Bay with researchers in the background.

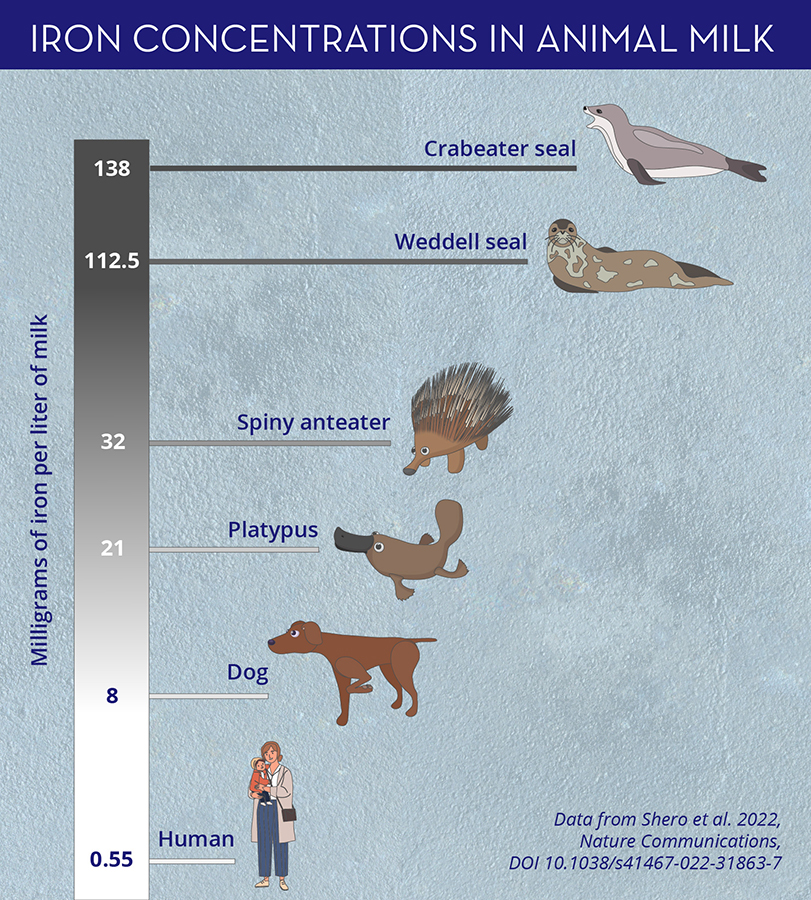

In muscle tissues, iron is bound to a protein called myoglobin, which is what gives skeletal muscle its dark color; the lighter the muscle, the less iron it has. Chickens, for example, store more iron in their thighs than breasts, so thigh meat is darker than breast meat. Weddell seal muscle has 20 times more myoglobin than terrestrial mammals, giving it an almost black coloring. Burns and her colleagues had been studying female Weddell seals and trying to assess what factors determine whether or not a female births a pup in any given year. They noticed postpartum females had lower iron concentrations in their blood and muscle and decided to look into it further. In the new study, the researchers compared concentrations of iron-containing proteins in females' blood and muscle in those who were nursing pups compared to those who didn't give birth. They examined 200 seals in Erebus Bay from 2010 to 2017, checking their iron levels at the beginning and end of lactation and after pups were weaned. The results showed postpartum females had significantly less iron stores in their blood and muscle tissues compared to females who didn't give birth. In fact, the breeding females transferred so much iron to their pups that their milk has 100 times more iron than human breastmilk. Among terrestrial and marine mammals, only crabeater seal milk has more iron in it, according to the study. The postpartum females in the study had a reduced diving capacity as a result of losing so much iron. On average, nonbreeding females had dives lasting around 16 minutes during the months of December, January, and February, but postpartum females only dove for around 12 minutes during those same months. While typical dives last 15-20 minutes, Weddell seals can actually hold their breath for up to 96 minutes at a time. “Their dive durations were significantly shorter, particularly in the mid-summer months there, which would be right after they had weaned their pups,” Burns said. A slow recoveryThe postpartum females should be able to replenish their iron stores as they capture prey during the winter months, but the researchers aren't sure how long that takes and if it affects their ability to get pregnant again. “We don't know how quickly they recover, and if it's variable across individuals, because they're out at sea at that point,” said Michelle Shero, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and lead author of the study. “We don't know exactly when they recover and if that will influence their next year's pregnancy.” Luckily the postpartum females' diving capacity is reduced during the Antarctic summer, when prey are most abundant and the seals don't have to work as hard to find food. But the Antarctic region is warming fast due to climate change, which may affect how much prey is available to them over the coming decades. “They don't need to work as hard to catch prey and they still do well, but as the climate changes, if the timing becomes mismatched in any way, that could be particularly detrimental for the animals,” Shero said. “When we consider what's important for these animals and their ability to catch prey, we've always thought about it about in terms of calories that the fish have. But the nutritional value of the fish and other species is maybe more important than we had thought about before if they equally need this iron.” This research is supported by the National Science Foundation, which manages the U.S. Antarctic Program. NSF-funded research in this story: Jennifer Burns, Texas Tech University, awards 1246463 and 0838892; Daniel Costa, University of California Santa Cruz, award 0838937. All research was conducted under scientific authorizations from the National Marine Fisheries Service (permit no. 17411-03). |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |