|

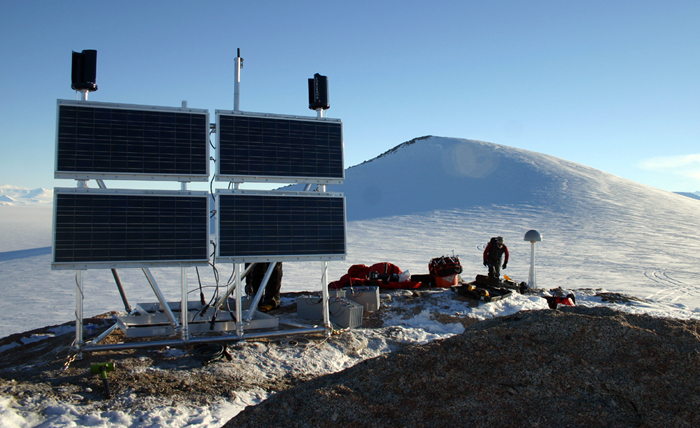

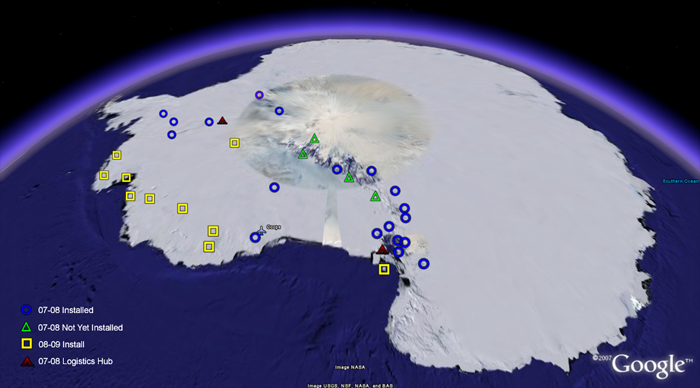

Making wavesThe data from seismometers, which record seismic waves from earthquakes, are also a key part of the equation. The material below the ice sheets is not uniform. It may be thick, dense and stiff. Or perhaps it’s weak and warm. The seismic waves can tell scientists what sits below the ice sheets, which indicates how quickly the crust may move up and down. “The speed at which [seismic waves] go is a direct recorder of the physical properties of the earth,” Wilson explained. “Integration of seismic and GPS is really important for understanding both short- and long-term ice mass balance. … It’s not entirely straightforward because you have these superimposed signals.” Seismic waves pass quickly through dense rock, but move slower through warm and “gooey” material. Under one area in West Antarctica, the material is weak and warm where the crust has pulled apart, meaning the rebound, the long-term response, may have already occurred. “The signal from the last glacial maximum could be gone because it’s relaxed that signal completely in the length of time that’s transpired, versus if we had really cold, dense lithosphere, then you’d have quite a lot of signal going on today,” Wilson said. Saving GRACEThe data from POLENET will be particularly useful to a separate project involving a pair of satellites that measure gravity field changes on Earth, according to Wilson. The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) Gravity is related to mass, so as mass grows or shrinks, such as with an ice sheet, the satellites can detect the changes. But one variable missing in its calculation is the rebound effect that POLENET measures. Wilson said a recent series of scientific papers point out that the biggest source of error in models attempting to account for Antarctica’s ice mass is the rebound calculation. In the next few years that should change. “They will have this very accurate means to track changes in the mass in the ice in a way that they intended to do,” Wilson said of the satellite-based study. “This is one of the reasons that POLENET got funded. It will make GRACE a very, very powerful tool,” noted Mike Willis, a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio State, who works on POLENET and its sister network in Greenland, GNET. In the future, using these tools, scientists will be able to say whether Antarctica grew or shrunk on at least a monthly basis, according to Willis. “We don’t even know that at this time. We have hints of it, but that’s based on models — which are probably wrong,” he noted. Setting up the networkThe United States’ component of the five-year project will establish 52 stations, though not all contain both GPS receivers and seismometers. Some 28 countries are involved in POLENET in some form or fashion, though the United States, Italy, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Germany are the principal partners in the West Antarctica venture. Each station runs year-round, using solar power in the summer and several hundred pounds of batteries to keep the instruments juiced through the winter. An Iridium modem sends the GPS data in real-time, but the seismic information is too large to send via satellite, so those sites require physical visits. Stephanie Konfal, a graduate student at OSU, was a member of this past season’s installation crew, which traveled across West Antarctica on ski-equipped aircraft to set up the stations. On a good day, she said, several people could install one station in about three to four hours. “It’s a pretty big setup per site,” she said. The team spent most of its time working out of Patriot Hills, the only privately run camp on the continent, used mainly by adventurous types for mountaineering expeditions and ski trips to the South Pole. “It was nice to be out in the field,” Willis said. “I hadn’t lived in a tent since 1998-1999. This was nice to be back to the old school. Old school but cushy — I mean the food was glorious.” Even more glorious for Wilson is the network that is taking shape. A map of the continent shows variously colored points where POLENET and other GPS and seismometer stations are located. The dots fringe the entire coast of Antarctica, even East Antarctica, while even more freckle the vast interior of West Antarctica. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |