Meteorites in the fieldSearch for space rocks requires spending weeks at a time in Antarctica's backcountryPosted Septemeber 25, 2009

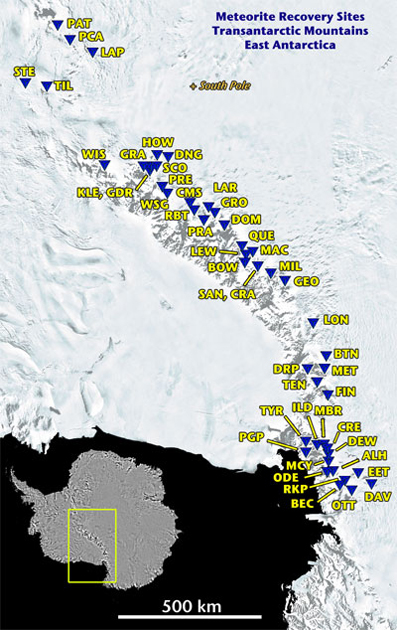

Last season was a tough one for the field team of the Antarctic Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET) It lost about a third of its six-week field season after discovering it would need to groom a runway for the Basler BT-67 that would support the team in the Dominion Range, part of the Transantarctic Mountains. A couple of days of work stretched into two weeks when the groomer equipment towed behind a snowmobile broke down. Blustery winds also cut into the field season, reducing the available working days to about 16. Yet the blue ice field between the Davis Nunataks and Mount Ward yielded 521 meteorites, helping swell the 33-year-old collection to about 17,500 specimens. “It’s going to turn out in the long run to be a very important place for us,” Ralph Harvey “There’s probably eight or nine times as much work to do there as we thought,” he added. “The funny thing is that’s very typical for us. You don’t really know what you’re going to find until you’re on the ground there.” Living out of tents for a month and sweeping across the ice on snowmobiles when good weather allowed, the six members of the ANSMET team found plenty of meteorites but also plenty of ordinary Antarctic rocks. “That slows you down dramatically. You pretty much have to put your eyeballs on every rock at least long enough to determine if it’s worth looking at more closely,” Harvey said. It takes a few days to recognize some of the telltale signs that differentiate a meteorite from terrestrial rocks, he explained. The most obvious feature is a blackened, burnt outer shell called a fusion crust that forms when the rock falls through the Earth’s atmosphere at great velocity. The heated entry into the atmosphere also tends to burn off the corners of the meteorites, making them more rounded. “We’re in an area where there’s a lot of terrestrial rock. We’re going to miss some meteorites. There’s not a question about it,” Harvey said. “I’m actually amazed at how many important specimens we have found in areas full of terrestrial rocks. A lot of our Martian meteorites and lunar meteorites have come from such areas.” Despite the challenges of weather and possible rock sensory overload, Antarctica is the best place to go meteorite hunting. The clear ice makes it easy for someone to spot the rocks from the back of a snowmobile. The most fruitful places tend to be the cold, blue ice fields abutting the mountains where the rocks pile up. But after more than 30 years of scouring Antarctica for meteorites, the easiest spots to reach have been picked over, requiring the ANSMET teams to go farther afield for specimens, according to Harvey. The National Science Foundation This will be the third season the ANSMET team has visited the Miller Range. “I’m looking forward to it. It’s a beautiful place,” Harvey said. “No telling what we’re going to find, but there are plenty of areas of blue ice that we haven’t searched yet.” This will be Harvey’s 20th field season for the ANSMET program, while Schutt has been working in Antarctica since the 1970s. However, half of the team members are rookies, recruited from the rank and file of the planetary sciences community. Antarctic meteorite curator at NASA’s Johnson Space Center “I think it’s a tremendous opportunity for people like me to experience not only being on the continent but seeing the operation we have there and seeing how it all works. It’s really eye-opening,” he said. “If you had the same team doing it every year there would be less appreciation, I think, and less participation. It’s a nice program to keep going.” NSF-funded research in this story: Ralph Harvey, Case Western Reserve University, Award No. 0839168 Return to main story: Rocking science. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |