Page 2/3 - Posted June 18, 2010

Paucity of productivityPAL LTER scientists reported last year in the journal Science that phytoplankton are also responding to climate change. Phytoplankton are single-celled plants that float near the surface of the ocean, obtaining energy through photosynthesis. They not only provide food for other organisms in the food web, such as the shrimplike krill and squishy salps, but also draw down carbon dioxide already dissolved in the ocean and release oxygen. Using satellite and field data from the last 30 years on ocean color, temperature, sea ice and winds, the PAL LTER researchers suggest the decline in sea ice and increase in wind speed cause greater mixing of the surface ocean waters. That forces phytoplankton deeper into the ocean, where there is less light, hurting productivity. It’s also forcing a shift from relatively large and juicy diatoms to smaller phytoplankton cells, which affect the food web and the cycling of carbon, according to Alex Kahl

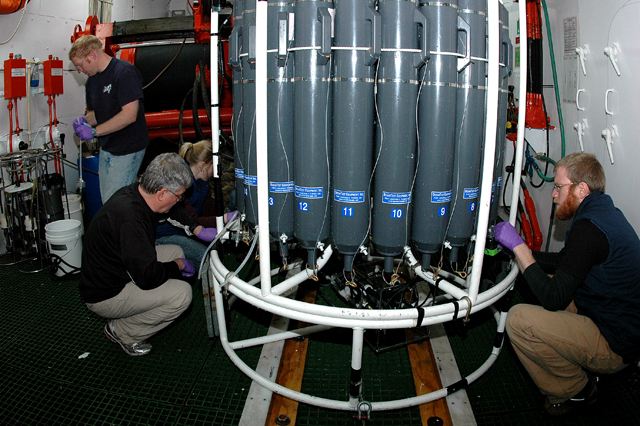

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Hugh Ducklow, left foreground, siphons water with the rest of the bacterial LTER team.

“Now you’re selecting for a type of phytoplankton that can do well with less light compared to another one,” explained Kahl, a tall, trim man with a Wyatt Earp mustache. The smaller cells are not only less nutritious but also less effective in transporting carbon to the deep ocean after they die. The bigger cells, like diatoms, fall faster, with a better chance of burying carbon. “That’s good because that’s isolating the carbon from the atmosphere on a long geological time scale,” Kahl explained. The more carbon buried in the ocean, the less of it is available to return to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping gas. Noted Michael Garzio Attack of the killer salpsAnother once-dominant, sea-ice dependent species decreasing in the north end of the peninsula is krill. In particular, the keystone species Euphausia superba is declining and appears to be moving closer inshore, while Salpa thompsoni are growing in numbers. Salpa thompsoni is a species of salp, a gelatinous, voracious tunicate that indiscriminately filters its food — a sort of free-floating, transparent water pump. While numerous and as large as krill, salps have little nutritional value, like the difference between eating popcorn versus prime rib. “We’re seeing shifts in the community structure in just the past 15 years or so. There’s definitely something going on,” said Joe Cope, a wild-haired technician in Debbie Steinberg’s “That’s probably attributable to the loss of sea ice on the shelf,” Cope said, referring to areas on the PAL LTER study grid over the continental shelf. “We’re starting to see larger and larger concentrations of salps over time in deep water off the shelf, and they may be expanding some onto the shelf.” Changing with the timesThe PAL LTER program is also changing with the times. For many years, the PAL LTER project followed the same script: Scientists would sail along a grid pattern, sampling the same 55 “stations” north to south and east to west — predetermined spots they would revisit each year by ship. They collect water samples to study the health, abundance and composition of bacteria and phytoplankton. Another group tows nets at each station to capture and characterize zooplankton, which includes larger animals like krill and salps. These “snapshots in time,” as Ducklow calls them, are important for the long-term records the program has collected over the last two decades. But they have their limitations, and over the last few years, the group has added new instruments to make year-round observations, and recruited new team members who offer different scientific techniques and equipment. “It’s taken us five to 10 years to come to grips with what’s happening here,” said Ducklow, a silver-haired scientist who speaks in a deep monotone. He joined the PAL LTER in 2001. “To really understand a system like this you probably need a century. The system is also changing as we’re studying it, and that makes it challenging as well.” Steinberg and Schofield are among the newest members of the PAL LTER team. In particular, Schofield’s lab employs autonomous underwater gliders that “fly” through the ocean on pre-programmed missions that can collect information about the ocean, such as temperature, salinity and optical properties. They can cover vast areas but with what scientists call high resolution. It’s another way of saying they have a dense collection of data over the area. “In just the first few weeks that we had the glider out last year, we collected as much data as the cruises had collected since 1993,” Ducklow noted. |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |