Page 2/2 - Posted September 24, 2010

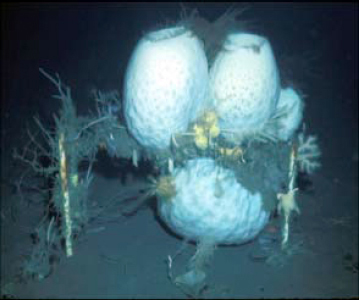

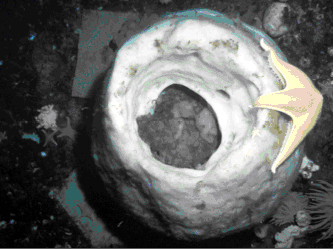

Changes through timeAlways central to that story was succession — how the different marine communities develop and change over time. Dayton has a record of when each experiment was set up over the course of more than two decades. The ICE AGED team will return to each of those artificial substrates, spread across McMurdo Sound, with divers and a special robot designed to work deeper under the ice to access and re-sample all the sites. “We’re not going to be so interested in what’s under the cages as what’s on the cages,” Kim said. During the three previous years in Antarctica, Kim and her team of scientists and engineers developed and tested a new kind of remotely operated vehicle, Submersible Capable of Under Ice Navigation and Imaging (SCINI) In its first season of operation, SCINI located many of Dayton’s “lost experiments,” some at depths well beyond today’s safety limit of 40 meters. The sites were photographed and marked with GPS, as opposed to Dayton’s method of lining up landmarks to find sites before the age of satellites. “It’s a record of succession that’s better than anywhere else,” noted John Oliver Oliver knows a bit about some of those experiments: Dayton was his greatest mentor, and Oliver helped set up some of those cages and substrates. He’s made about 10 trips to the Ice himself. His interests these days mostly focus on human impacts to marine ecosystems and habitat restoration. But his motivation for doing the ICE AGED expedition is pretty simple: “If Paul dies tomorrow, 40 years is gone. We’ve saving a time series,” he said. “Every year that goes by, those data become more valuable.” The scientists are interested in not only comparing the past to the present, but also creating a baseline against which future changes can be measured, according to Kim. “The biggest thing that will come out of this is that we will take all of the information and all of this data into a big database that will be available to anybody internationally,” Kim explained. The data will be fed to the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research Marine Biodiversity Information Network (SCARMarBIN) The temporal and spatial comparisons of the different sites should give the ICE AGED researchers a better understanding of succession in an ice-covered environment, Kim noted. For example, do species compete and reproduce on an annual basis, or are there periodic booms and busts based on environmental conditions that occur over the longer time scale of decades? “If there are abrupt jumps and breaks in the colonization sequence between one year and the next year between the different substrates, then we can say something happened there in that particular year,” Kim said. In addition to photographing the environment, project divers will collect plenty of organisms for morphological and taxonomic studies back at Scripps, Kim said. It turns out the sea star in McMurdo Sound and the one found off the Antarctic Peninsula may look alike but could turn out to be different species. “What we’ve been finding is that there are far more species in Antarctica than we have described from just a morphological perspective,” she said. “Molecular taxonomy can allow you to look into that in greater detail.” Over the generationsWhile always interested in the details, Dayton built his reputation on being able to see the big picture. One of the world’s preeminent marine ecologists today, Dayton still conducts research into coastal and estuarine habitats around the world, including benthic and kelp communities. His studies also include the impact of overfishing on marine ecosystems. “To me he is the Charles Darwin of marine ecology. To spend three months with him in Antarctica is something I couldn’t pass up,” said Jennifer Fisher, a larval ecologist at the University of Oregon who will be one of the project’s divers. In fact, Fisher represents the latest generation of the Dayton legacy in Antarctica. Dayton mentored Oliver, who was an advisor to Kim. Fisher worked in Kim’s lab at Moss Landing and made two previous trips to the Ice. “We’re going to have four scientific generations that are going to be on this project, and that’s a thrilling thing,” Kim said. “That’s the sort of continuity you need across these long timescales.” The connections don’t end there. Kevin O’Connor is another diver and research technician on the project. His father, Ed O’Connor, dived in McMurdo Sound with Dayton and Oliver in the 1970s. “It’s just fun as hell to have the next generation come through,” Oliver said. Scientists build reputations on scientific papers. It’s what they do for a living. Dayton’s seminal work, a paper published in 1971 titled “Competition, disturbance and community organization: The provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky intertidal community” has been cited more than 1,400 times, a remarkable number. That seems less important to Dayton than a different number — the more than 30 students he’s worked with and tutored over the years. “Even the best papers should go extinct. Science moves on,” he said. “If you’ve done a good job of mentoring students, that doesn’t go extinct. It continues, and they mentor more students. If there’s anything I would take pride in, it’s my students.” NSF-funded research in this story: Paul Dayton, University of California-San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Award No. 0841538 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |