Extreme environmentScientists drill into frozen Lake Vida to explore its unusual biology, chemistry and historyPosted March 11, 2011

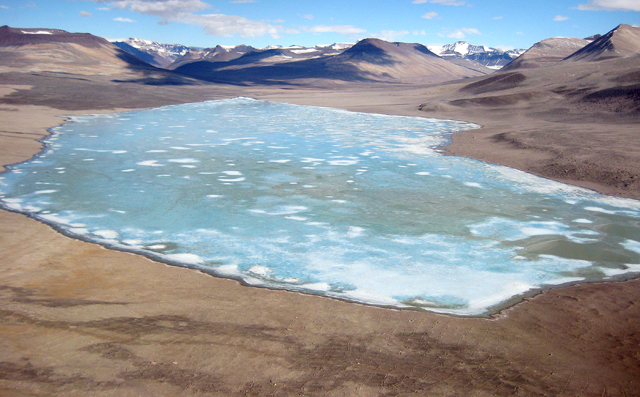

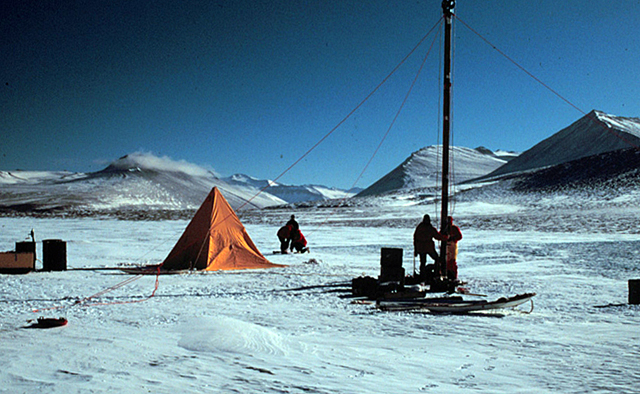

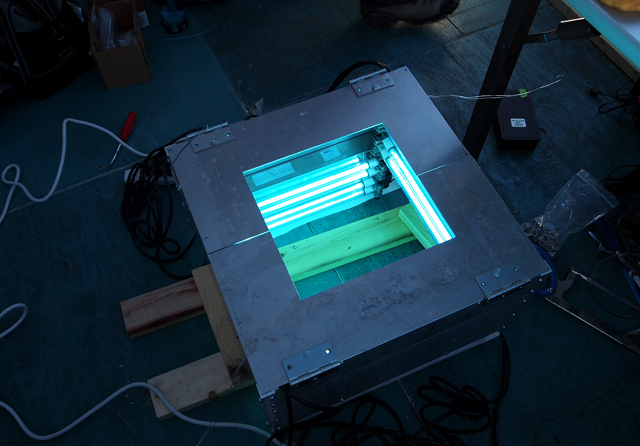

Lake Vida isn’t a particularly accommodating place to live. Consider that the Antarctic lake would hardly fall under the definition of “lake” for most people. It certainly wouldn’t be found on anyone’s top ten list of favorite fishing holes. In fact, neither fish nor much else could survive in the hypersaline lake, which appears to be frozen from the surface to nearly the bottom more than 20 meters down. Oxygen is completely absent from Lake Vida, which is up to seven times saltier than seawater. Its chemistry is just weird, with the highest nitrous oxide levels of any natural water body on Earth. A briny liquid that courses through pockets and channels within this anaerobic environment exists at minus 13.5 degrees centigrade. Remember that the ocean never gets colder than a couple of degrees below zero. “It’s so cold that we know very few liquid ecosystems on the planet where the constant temperature is that far below zero,” said Alison Murray “We don’t know much about cellular processes — what it takes to make a living — at that temperature,” added Murray, a principal investigator on a collaborative project Other members of the team, led by Peter Doran “The main goal is to get into that brine pocket and the sediment beneath it to both document and define the ecosystem that's there today, and the history of that ecosystem,” Doran said previously. That’s exactly what Murray, Doran and their team attempted to do this past season: Probe deep into the lake to learn more about its biology, chemistry and history. And, as one might expect when exploring such an alien environment, they turned up the unexpected. The first breakThe 2010-11 expedition is the third visit to Lake Vida in about 15 years by U.S. scientists interested in its unique characteristics. In October 1996, researchers extracted two ice cores from Lake Vida with an electromechanical drill, spending about two weeks at temperatures below 35 degrees Celsius to drill through 16 meters of ice. A paper six years later in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, with Doran as the lead author, announced that Vida was not completely frozen and lifeless as previously assumed. Ground-penetrating radar, ice core analyses, and long-term temperature data, showed that Vida had a thick, light-blocking ice cover, a vast amount of ancient organic material and sediment, and a cold, super-salty, liquid layer below the ice. Carbon dating placed the age of the microbes recovered and revived from the ice cores at some 2,800 years old. Going deeperDoran and colleagues returned to Lake Vida in 2005 with the intent of drilling through the ice cover into the liquid brew underneath. That’s when Murray got involved in the project, joined by DRI colleague Chris Fritsen The second attempt not only had the support of the National Science Foundation The conditions at Lake Vida could mimic those found on Mars or Jupiter’s moon Europa, destinations where the space agency hopes one day to search for life. A lightweight, functional drill might be needed aboard a future mission to probe into a similarly ice-covered environment. Meanwhile, a second drill operated by a crew from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Keeping it clean“One of the big things we developed for that project was to develop clean access procedures,” Murray said, explaining that the scientists wanted to keep the environment that was believed to exist about 20 meters under the ice as pristine as possible. Potentially, it hadn’t been in contact with the atmosphere for thousands of years. Strong winds in Victoria Valley, the northernmost of the McMurdo Dry Valleys where Lake Vida sits, blow across sand dunes on one side of the 5-kilometer-long lake. The team didn’t want the sediments to end up in their hole. So they set up stringent procedures to keep the drill site and equipment clean, working under a tent constructed on the lake’s surface. Everything that went down the hole was sterilized like a surgical tool. An ultraviolet light system under the floor of the tent gave the instruments a final dose of UV radiation for good measure. “The cleaning part of this is quite a process,” Murray said. The team even developed a way to clean the drill hole itself. After initially drilling a hole, they would widen it, and then clean the hole of all the water through a filtration process. They then would let the water in the hole refreeze, drilling through again into a clean ice “pipe” to sample the brine below the ice.1 2 3 Next |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |