Page 3/3 - Posted March 11, 2011

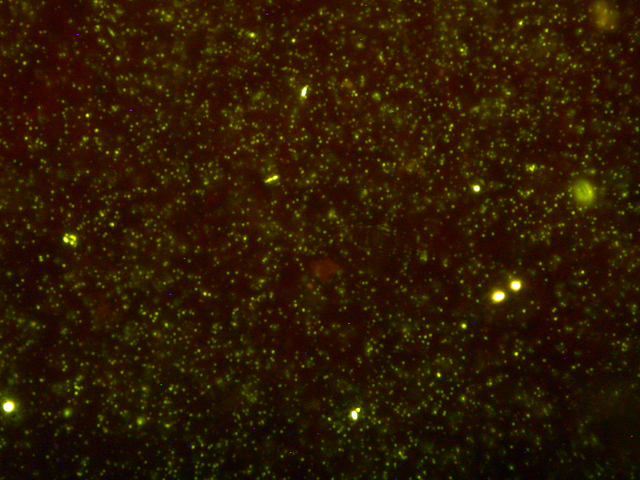

Time will tellMeanwhile, Hilary Dugan A PhD student with Doran, Dugan is interested in the physics and history of the lake system. The absence of a liquid layer could mean many different things. Perhaps the lake has frozen solid to the bedrock since the GPR survey 15 years ago. Maybe the spot where the team drilled was on a high point of the lake. “We sort of have to readjust how [we think] the lake formed, which is neat because there’s no other lake in the world that has this much ice frozen right to the bottom with that amount of life, that amount of carbon in it,” Dugan said. Dugan, with the help of the McMurdo Station Field Safety Training Program team, conducted a new GPR survey of the lake, hoping an updated view of the layers below the ice cover will tell the scientists something about that missing water pocket. Speaking later via e-mail from the States, Doran said the team will meet soon to discuss the results of the latest radar survey to determine what the collaborators believe might be happening. “I think the leading candidate right now is that the lake is a sequence of dunes migrating over top of the lake, then more lake ice, then more dune migration, etc.,” he said. Additionally, there may be some muddy floodwaters mixed in the lake as well. Laboratory work back in the States on the ice-sediment sequences in the core might provide some clues as to what happened in the past despite the mixed layering, according to Doran. “The problem with ice in this system is it comes and goes, and so we may not have a continuous sequence,” he said. “Sediments can tell you about the history and chemistry of the lake over time. So we’ll get our record, but it will be tricky and probably the timeline is going to be hard to nail down with as much accuracy.” So close, so differentEach body of water in the Dry Valleys seems to possess its own unique history, making it difficult to compare lakes within the same valley, let alone the whole region. It seems surprising, given the whole region is only 4,800 square kilometers. Doran explained that Lake Vida is unique because Victoria Valley is sheltered from winter katabatic winds that normally warm the valleys. That means it’s colder in Victoria Valley than farther south, allowing the lake’s ice cover to grow. The summer melt that later pools on top of the lake just adds to the thickness. In fact, the lake ice cover has grown about a meter in the last decade, according to Dugan. “That’s a lot of hydrological input,” she said. The Dry Valleys have always been a favorite analogue for scientists with a yearning to understand life beyond Earth. Vida may be the most alien of all. “You can imagine you’re walking on Mars,” Dugan said, returning to the theme of planetary research that the Lake Vida project represents. “We might have a system that’s closer to life on other planets than other places in the Dry Valleys.” Links to the past and futureLake Vida is also an interesting model for those interested in studying ancient climate right here, when the planet was periodically in a deep freeze called Snowball Earth. Some scientists believe much of the planet, all the way to the equator in some models, was covered by ice hundreds of millions of years ago. Murray said that it’s possible that Snowball Earth “That’s a good link to past history on Earth,” she said. A more tangible connection that Murray hopes to make as she gets into the genetic level of the study is how the Lake Vida microbial community compares to relatives of bacteria from other places on the planet. What adaptations do the lake extremophiles show compared to their cousins in less stressed environments? “One of the biggest legacies I think we can get from this system is having a culture collection of diverse organisms that are from there and capable of life at minus 13.5. It could prove to be really useful models for studying cryobiology,” she said. “I’m quite interested in the diversity of those organisms.” NSF-funded research in this story: Peter Doran and Fabien Kenig, University of Illinois at Chicago, Award No. 0739698 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |