|

Page 2/2 - Posted July 5, 2013

Antifreeze protein only one evolutionary strategy for living in cold waterFinding the fish is half the challenge. Until the last decade, it was relatively easy to capture mawsoni in McMurdo Sound, where DeVries and colleagues have established favorite fishing holes near the U.S. Antarctic Program’s Despite nearly three weeks of fishing during the 2011-2012 season, the team, working with New Zealand colleagues at nearby Scott Base, caught just one Antarctic toothfish, a specimen barely weighing five kilograms. “It was the smallest one we’d ever seen [from McMurdo Sound],” Cziko said.

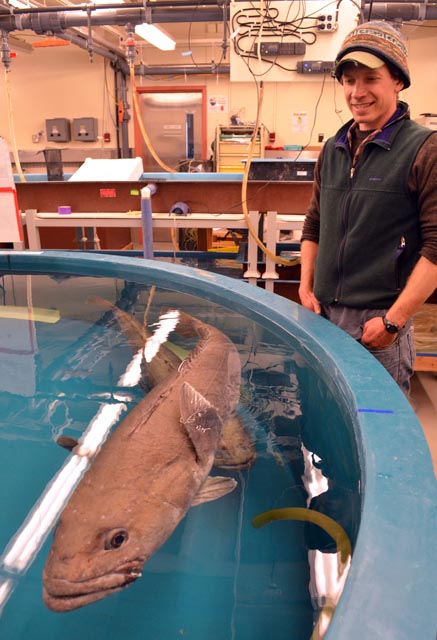

Photo Credit: Peter Rejcek

Scientist Paul Cziko observes an Antarctic toothfish in the Crary Lab aquarium room.

Some researchers and conservationists believe that a commercial fishery operating in the nearby Ross Sea A change in fishing technique by the scientists this season — fishing horizontally near the seafloor instead of vertically throughout the water column — yielded about 20 specimens. “We need to catch them so we can get their tissues and [determine] how they’ve changed their gene expression for adapting to the cold here,” Cziko said. Genetic expression refers to which genes of an organism may be “turned on” or “turned off” under different environmental conditions. “In the future, it may be impossible to catch [mawsoni] here. It’s great to have a last hurrah here in a way,” Cziko said. Still, despite almost daily fishing trips for weeks, the catch was relatively modest, with no fish weighing more than 40 kilograms, less than half the size that DeVries and his teams would catch before the fishery started operations more than a decade ago. “The fishery targets the big fish,” Cziko noted. In addition, neutral buoyancy is an ability that comes later in life for mawsoni, so those near the seafloor are likely to be younger and smaller because they’re unable to “float” up the water column. The scientists need a range of fish sizes and ages to understand the different genetic strategies for survival at various stages through its life history. For example, fish larvae with a different species from a family of notothenioids called Bathydraconidae (Antarctic dragonfish) possess very little of the antifreeze protein. Instead, they rely on skin as a barrier to freezing. “The story is really complex. It seems to be quite different for each species. There seems to be different strategies for surviving this ocean at those young ages,” Cheng said. “Antifreeze is no longer the whole story.” Another chapter in this story involves the ice crystals within the blood of the fish that the antifreeze protein neutralizes. They don’t simply go away. Instead, they accumulate in the spleen. “In this perennially, constantly cold water, once a fish gets an ice crystal in its body, it might be there for good,” Cziko said. Scientists aren’t quite sure why sure why the ice crystals end up in the spleen, though the organ primarily filters blood. Cheng likens the presence of ice crystals to the painful condition in humans called gout, caused by uric acid crystals accumulating in the joints. However, the Antarctic fish don’t seem to be adversely affected by the foreign object in their body. Next year, Cheng and other team members will travel to the other side of the Antarctic continent to collect additional specimens from the research vessel Laurence M. Gould

Photo Courtesy: Paul Cziko

Water is added to a tank containing Antarctic fish inside a hut on the McMurdo Sound sea ice.

One particularly elusive species, Lepidonotothen squamifrons, the grey rock cod, first found by DeVries around the Belleny Islands between Antarctica and New Zealand in the 1970s, is a notothenioid without the antifreeze protein. However, it somehow navigates its ways through layers of the water column where warmer temperatures prevail. Specimens of grey rock cod were found near Palmer Station “It still won’t tell us why [L. squamifrons] can survive without the protein, but at least at the genetic level we can find out what happened to the DNA sequence that led to the absence of the protein,” she explained. The two-month voyage will also offer the researchers a greater variety of Antarctic fish species for their studies on the ice crystals found within the bodies of the organisms. The antifreeze protein is certainly a boon in one sense — but because it binds so tightly to ice, it also prevents ice crystals from melting as temperatures warm up. “This is the neat thing about evolution … You solve one problem but create another problem,” Cheng observed. “The plot thickens.” NSF-funded research in this article: Christina Cheng and Art DeVries, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Award No. 1142158 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |