|

Page 2/2 - Posted January 21, 2015

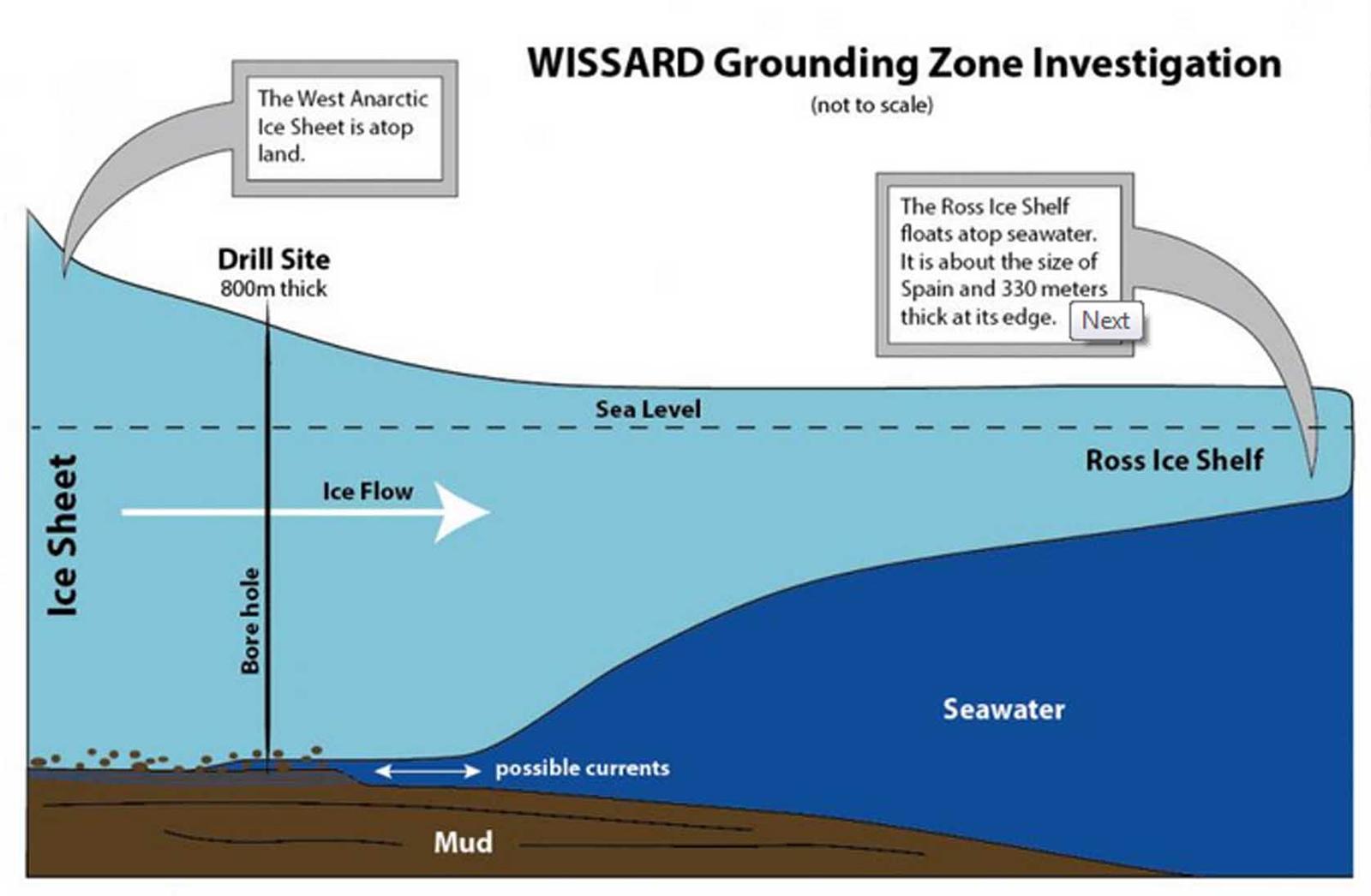

Scientists investigate ice shelf stability at grounding zoneThe discovery of life under the Ross Ice Shelf is remarkable, but the main thrust of this year’s project is to investigate the grounding zone where the floating ice shelf lifts off from the seafloor. The grounding zone is important for the stability of an ice shelf. Numerous glaciers feed into the Texas-sized Ross Ice Shelf, like streams flowing into a lake. Scientists are particularly interested in the dynamics between the ice, glacial sediments and water in order to understand how the system may respond to future changes in climate. Some climate models predict warmer seawater may intrude into grounding zones and cause melting at the base of the ice shelf. A weakening or collapse of the Ross Ice Shelf would allow glaciers, or rivers of ice, to flow more rapidly into the ocean, which would raise global sea level. “This season we accessed another critical polar environment, which has never been directly sampled by scientists before: the grounding zone of the Antarctic ice sheet,” noted Slawek Tulaczyk, a chief scientist on the WISSARD project and a professor from the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Nobody has ever actually done direct measurements in an environment like this.” Lake Whillans, a shallow body of water located about 800 meters below the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, periodically fills and drains near the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. The fresh water from the lake, carrying fine-grained sediment called till, eventually reaches the seawater cavity under the Ross Ice Shelf through a subglacial waterworks that may be similar to a wetlands ecosystem – but covered in ice. Tulaczyk said that one hypothesis suggests that the destabilizing effect of warmer seawater may be counteracted by accumulation of glacial sediments at grounding zones. “These glacial sediments form so-called grounding zone wedges, which act like defensive ramparts preventing grounding-zone retreat,” he explained. “One goal of our investigation is to collect samples and data which will help determine if the delicate balance between ocean warming and sediment accumulation at grounding zones may break down and increase Antarctic contribution to future sea-level rise.” The investigation under the Ross Ice Shelf will also help scientists understand the freshwater system that is connected to Lake Whillans, located “upstream” about 100 kilometers away. “We treat them as a linked system because they’re all part of the ice plain where the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is going into the ice shelf,” said Ross Powell, a professor at Northern Illinois University and one of the three chief scientists on the WISSARD project. “They’re linked hydraulically.” Whillans is one of several hundred subglacial lakes that researchers have identified. The largest and most well-known is Lake Vostok, which is estimated to be the size of Lake Ontario. Lake Vostok is believed to be a deep, isolated body of water that has existed for millions of years. In contrast, Lake Whillans fills and empties periodically and is likely ephemeral. “These active lakes have really piqued our interest because they allow us to pinpoint the most dynamic part of the hydrological system,” Tulaczyk said. The hydrological system is important because it may play a key role in how ice moves. For instance, the Whillans Ice Stream that flows above the subglacial lake exhibits what’s been dubbed as “stick-slip” behavior. Instead of steady movement, the ice stream jerks forward like clockwork twice a day by tidal motion at the Ross Ice Shelf grounding zone. An ice stream is a region within the ice sheet that moves faster than the surrounding ice. Those hydrologic studies are still ongoing, as is the investigation into the nature of life in a subglacial lake. In August 2013, WISSARD researchers published a paper in the journal Nature that reported a large diversity of microbial life, with upwards of 4,000 species. “It’s not simple system at all,” said Brent Christner, a professor of biology at Louisiana State University and co-principal investigator on the WISSARD project who was the lead author on the Nature paper. “The diversity of this ecosystem suggests intense interactions.” Rather than relying on photosynthesis, converting energy from the sun, many of the microbes in subglacial Lake Whillans subsist on chemical energy by mining rocks and using carbon dioxide as their source of carbon. “Microbes that eat rock. It doesn’t get cooler than that,” Christner said. At least not yet. NSF-funded research in this story: John Priscu, Mark Skidmore and Andrew Mitchel, Montana State University, Award No. 0838933 |

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |