The Dissolving Sentinels of the Southern Ocean (cont.)Posted March 24, 2016

What’s concerning to these researchers is that the dissolution they’re already seeing in pteropod shells will most likely continue to get worse. As more carbon dioxide gets released into the atmosphere, more will mix into the oceans the world over, making them more acidic. Cold water is better at absorbing atmospheric gases than warmer water, so the effects on the pteropods that live in the frigid Ross Sea will be the most acute.

Photo Credit: Michael Lucibella

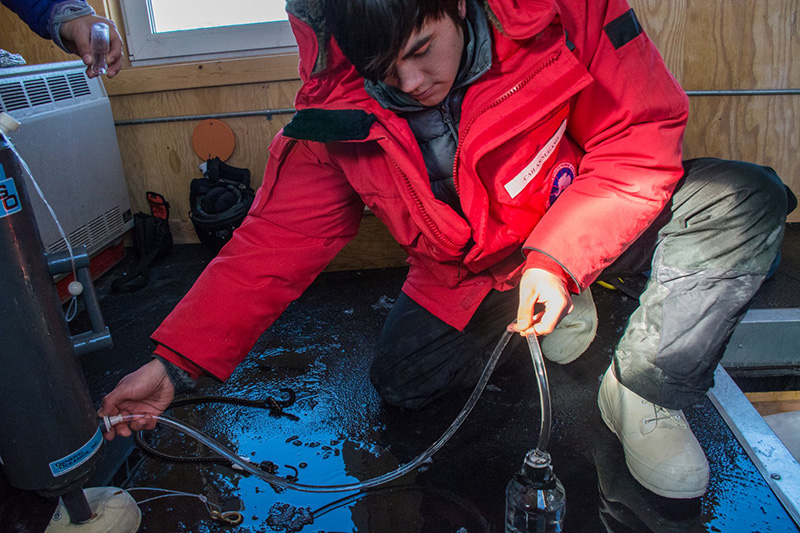

Umi Hoshijima dives into a hole drilled into the ice at Cape Evans to collect a water sample

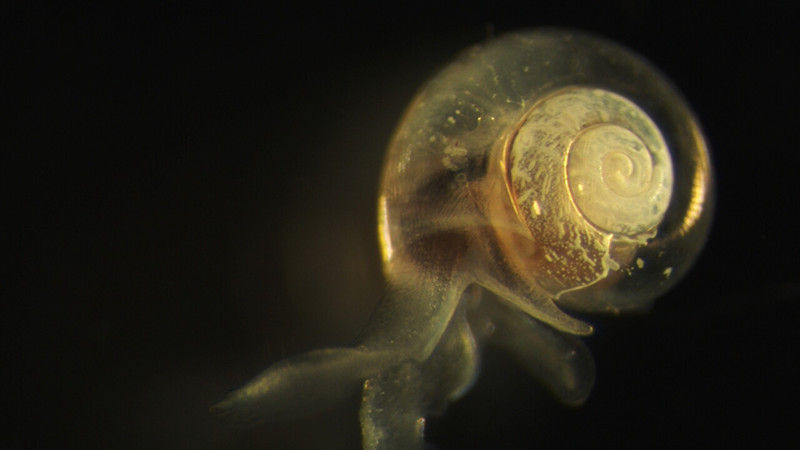

“This is the first time we’ve actually been able to see this on these guys,” Johnson said. “One of the things we still don’t know is what is the effect of this dissolution on their physiology.” To see what the future might hold for pteropods’ shells and their overall ability to thrive, the team ran an experiment exposing a selection of their specimens to the projected atmospheric carbon dioxide levels for the years 2050 and 2100. Though a more complete analysis of the shells will have to wait until the team can fully process their thousands of samples under an electron microscope in the United States, early results show that the shells are likely to keep dissolving at an accelerated rate as carbon dioxide levels increase in the earth’s atmosphere.

Photo Credit: Michael Lucibella

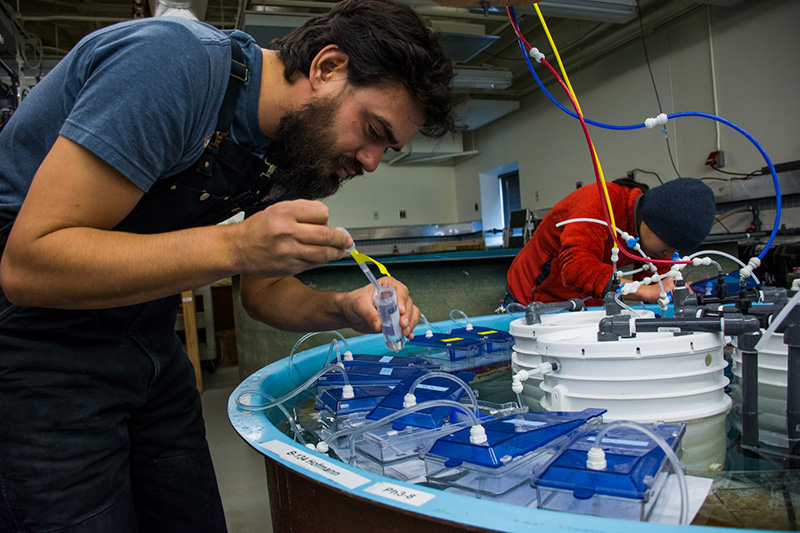

Cailan Sugano extracts a water sample from a Niskin bottle. The sample will be used to calibrate a sensor measuring the pH of the ocean over the year.

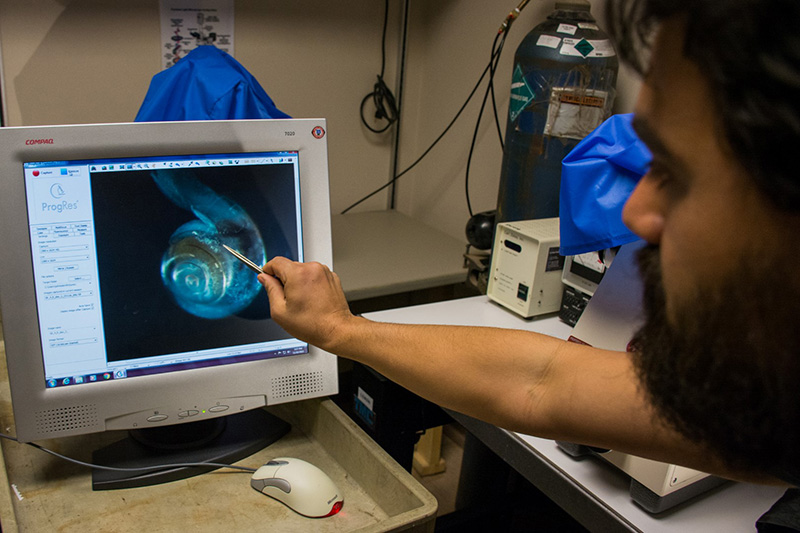

After the pteropods spent a few weeks immersed in the heightened carbon dioxide levels, Juliet Wong carefully placed the live animals in to an array of small vials, each hooked up to separate oxygen monitors. The device tracks their oxygen consumption as they respire, which is a good proxy for their overall metabolism. At the bottom of each vial, a meter reads how much oxygen is left in the water every sixty seconds for nine hours. “We can put the pteropods in and hold them at a discrete temperature and essentially measure how much oxygen they are using up while they’re hanging out in there,” said Wong, a graduate student at UCSB. The healthier they are, the more oxygen they consume. Again, the team is still sifting through their data, but it seems to indicate that the snails have a much harder time thriving in acidic water. If that’s the case, it could have serious implications on the future survival of other creatures throughout the Ross Sea.

Photo Credit: Michael Lucibella

Kevin Johnson and Juliet Wong tend to their tanks of pteropods growing in the Crary Lab. They’re studying how the sea snails are affected by elevated carbon dioxide in the water.

“They’re the base of a really fragile food chain,” Johnson said. “They play such a critical role here in the Antarctic, it’s imperative for us to understand what’s happening to them.” Pteropods are pervasive throughout the Ross Sea, and are important foundations of the Antarctic food web. They contain a lot of lipids, making them an important source of fat to marine life. “They’re fish food, and the fish that eat them are also important food for penguins and seals,” Hofmann said. She added that research has shown that pteropods make up to 80 percent of the diets of some species of fish that penguins rely on.

Photo Credit: Michael Lucibella

Juliet Wong points to a device designed to track sea snails’ metabolism by measuring their oxygen consumption.

The implications of their research extend to creatures beyond the Antarctic. Similar kinds of pteropods make up the foundations of marine food chains around the world. Near Washington State, they comprise up to 40 percent of the diet of commercial salmon. Likely the research could carry over to understand how acidifying oceans affects other ocean life as well. “At home in California, I work on red abalone, which are also sea snails” Wong said.

Photo Credit: Michael Lucibella

Kevin Johnson points to a pteropod’s shell showing signs of dissolution from elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. The levels in their tank mimic what the oceans are predicted to be the year 2100.

The genetic analysis that Johnson has been working on over the last few seasons could also help serve as an early indicator of other oceans where pteropod populations are threatened. “I took samples to look at gene expression to see if we could see signs if they’re physiologically stressed at a genetic level,” Johnson said. He’s been analyzing the transcriptome of these pteropods. Essentially, he’s looking to see which genes individuals turn on when their survival is threatened by adverse environmental conditions. “It’s like a physiological fingerprint that you could look at,” Hofmann said. “Once we figure out the pattern we could look at any pteropods in the world and say, ‘Oh yeah, those guys are stressed.’” It’s this reason that researchers like Hofmann and others consider Antarctic pteropods a sentinel organism, a creature at the frontline of climate change. They’re harbinger organisms in a region that has been warming faster than anywhere else. “Down here is an opportunity to look at an animal that’s really touched by climate change,” Johnson said. NSF-funded research in this story: Gretchen Hofmann, University of California-Santa Barbara, Award No. 1246202 |

"News about the USAP, the Ice, and the People"

For USAP Participants |

For The Public |

For Researchers and EducatorsContact UsU.S. National Science FoundationOffice of Polar Programs Geosciences Directorate 2415 Eisenhower Avenue, Suite W7100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Sign up for the NSF Office of Polar Programs newsletter and events. Feedback Form |